From The MPG Institute for Radio Astronomy [MPG Institut für Radioastronomie](DE)

June 28, 2022

Dr. Norbert Junkes

Press and public relations

Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy, Bonn

+49 2 28525-399

njunkes@mpifr-bonn.mpg.de

Dr. Arnaud Belloche

Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy, Bonn

+49 228 525-376

belloche@mpifr-bonn.mpg.de

Prof. Dr. Karl M. Menten

Director at the Institute and Head of the “Millimeter and Submillimeter Astronomy” Research Dept.

Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy, Bonn

+49 228 525-471

kmenten@mpifr-bonn.mpg.de

Interstellar detection of iso-propanol in Sagittarius B2

Many of us have probably already – literally – handled the chemical compound iso-propanol: it can used as an antiseptic, a solvent or a cleaning agent. But this substance is not only found on Earth: researchers led by Arnaud Belloche from the Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy in Bonn have now detected the molecule in interstellar space for the first time. It was observed in a “delivery room” of stars-the massive star-forming region Sagittarius B2 which is located near the centre of our Milky Way. The molecular cloud is the target of an extensive investigation of its chemical composition with the ALMA telescope in the Chilean Atacama Desert.

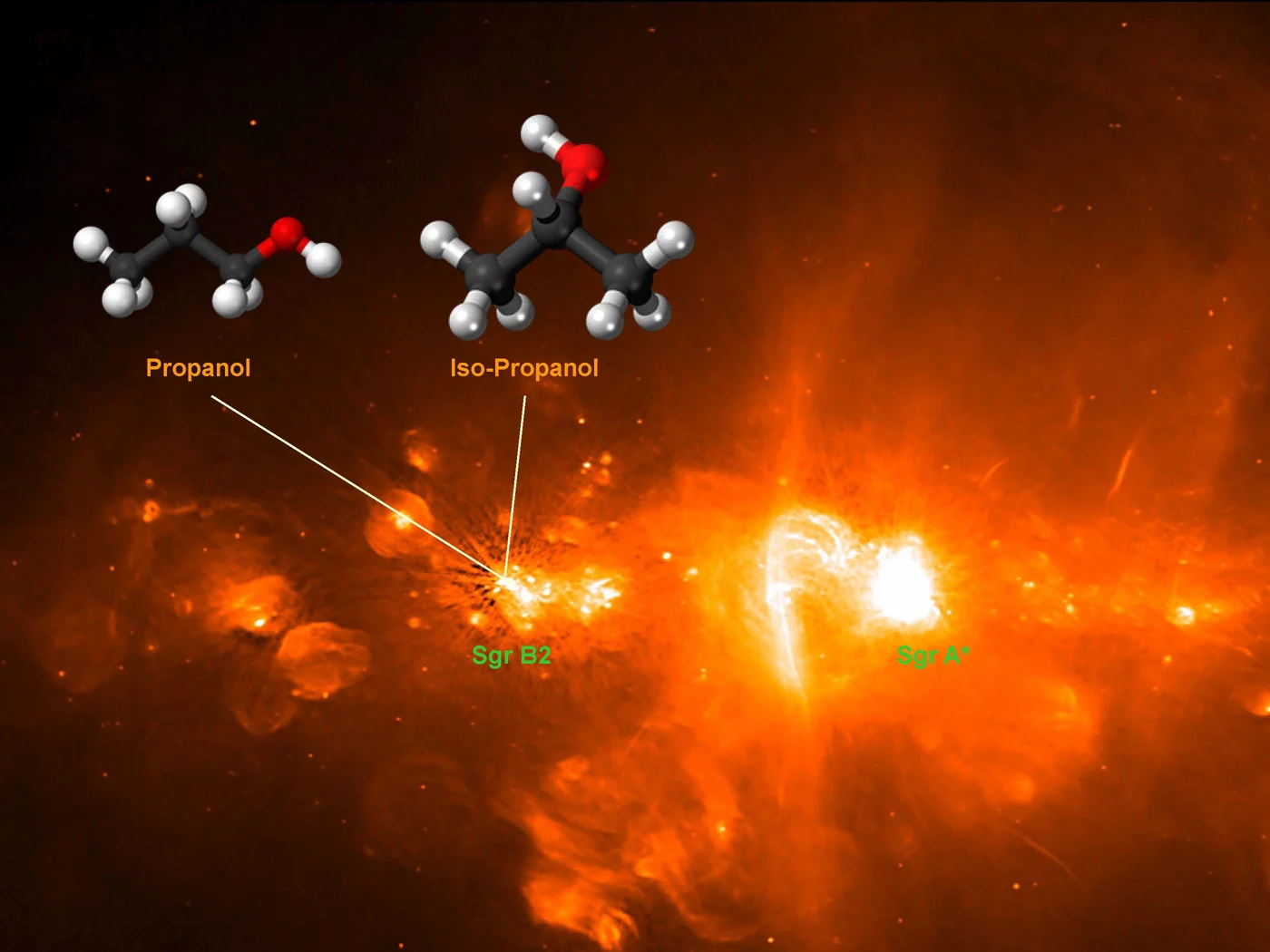

Alcohol in space: the position of star-forming molecular cloud Sagittarius B2 (Sgr B2) close to the central source of the Milky Way, Sgr A*. The image, taken from the GLOSTAR Galactic Plane Survey (Effelsberg & VLA) shows radio sources in the Galactic centre region. The isomers propanol and iso-propanol were both detected in Sgr B2 using the ALMA telescope.

© GLOSTAR (Bruntaler et al. 2021, Astronomy & Astrophysics): Background image. Wikipedia (public domain): Propanol and isopropanol models.

The search for molecules in space has been going on for more than 50 years. To date astronomers have identified 276 molecules in the interstellar medium. The “Cologne Database for Molecular Spectroscopy (CDMS)” provides spectroscopic data to detect these molecules contributed by many research groups and has been instrumental in their detection in many cases.

The goal of the present work is to understand how organic molecules form in the interstellar medium, in particular in regions where new stars are born, and how complex these molecules can be. The underlying motivation is to establish connections to the chemical composition of bodies in the Solar system such as comets, as delivered for instance by the Rosetta mission to comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko a few years ago.

An outstanding star forming region in our Galaxy where many molecules were detected in the past is Sagittarius B2 (Sgr B2), which is located close to the famous source Sgr A*, the supermassive black hole in the centre of our Galaxy.

“Our group began to investigate the chemical composition of Sgr B2 more than 15 years ago with the IRAM 30-m telescope”, says Arnaud Belloche from the Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy (MPIfR) in Bonn/Germany, the leading author of the detection paper.

“These observations were successful and led in particular to the first interstellar detection of several organic molecules, among many other results.”

With the advent of the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) ten years ago it became possible to go beyond what could be achieved toward Sgr B2 with a single-dish telescope and a long-term study of the chemical composition of Sgr B2 was started that took advantage of the high angular resolution and sensitivity provided by ALMA.

So far, the ALMA observations have led to the identification of three new organic molecules (iso-propyl cyanide, N-methylformamide, urea) since 2014. The latest result within this ALMA project is now the detection of propanol (C3H7OH).

Propanol is an alcohol, and is now the largest in this class of molecules that has been detected in interstellar space. This molecule exists in two forms (“isomers”), depending on which carbon atom the hydroxyl (OH) functional group is attached to: 1) normal-propanol, with OH bound to a terminal carbon atom of the chain, and 2) iso-propanol, with OH bound to the central carbon atom in the chain. Iso-propanol is also well known as the key ingredient in hand sanitizers on Earth. Both isomers of propanol in Sgr B2 were identified in the ALMA data set. It is the first time that iso-propanol is detected in the interstellar medium, and the first time that normal-propanol is detected in a star forming region. The first interstellar detection of normal-propanol was obtained shortly before the ALMA detection by a Spanish research team with single-dish radio telescopes in a molecular cloud not far from Sgr B2. The detection of iso-propanol toward Sgr B2, however, was only possible with ALMA.

“The detection of both isomers of propanol is uniquely powerful in determining the formation mechanism of each. Because they resemble each other so much, they behave physically in very similar ways, meaning that the two molecules should be present in the same places at the same times”, says Rob Garrod from the University of Virginia. “The only open question is the exact amounts that are present – this makes their interstellar ratio far more precise than would be the case for other pairs of molecules. It also means that the chemical network can be tuned much more carefully to determine the mechanisms by which they form.”

The ALMA telescope network was essential for the detection of both isomers of propanol toward Sgr B2, thanks to its high sensitivity, its high angular resolution, and its broad frequency coverage. One difficulty in the identification of organic molecules in the spectra of star forming regions is the spectral confusion. Each molecule emits radiation at specific frequencies-its spectral “fingerprint”-which is known from laboratory measurements.

“The bigger the molecule the more spectral lines at different frequencies it produces. In a source like Sgr B2, there are so many molecules contributing to the observed radiation that their spectra overlap and it is difficult to disentangle their fingerprints and identify them individually”, says Holger Müller from Cologne University where laboratory work especially on normal-propanol was performed.

Thanks to ALMA’s high angular resolution it was possible to isolate parts of Sgr B2 that emit very narrow spectral lines-five times more narrow than the lines detected on larger scales with the IRAM 30-m radio telescope! The narrowness of these lines reduces the spectral confusion, and this was key for the identification of both isomers of propanol in Sgr B2. The sensitivity of ALMA also played a key role: it would not have been possible to identify propanol in the collected data if the sensitivity had been just twice worse.

This research is a long-standing effort to probe the chemical composition of sites in Sgr B2 where new stars are being formed, and thereby understand the chemical processes at work in the course of star formation. The goal is to determine the chemical composition of the star forming sites, and possibly identify new interstellar molecules. “Propanol has long been on our list of molecules to search for, but it is only thanks to the recent work done in our laboratory to characterize its rotational spectrum that we could identify its two isomers in a robust way”, says Oliver Zingsheim, also from Cologne University.

Detecting closely related molecules that slightly differ in their structure (such as normal- and iso-propanol or, as was done in the past: normal- and iso-propyl cyanide) and measuring their abundance ratio allows the researchers to probe specific parts of the chemical reaction network that leads to their production in the interstellar medium.

“There are still many unidentified spectral lines in the ALMA spectrum of Sgr B2 which means that still a lot of work is left to decipher its chemical composition. In the near future, the expansion of the ALMA instrumentation down to lower frequencies will likely help us to reduce the spectral confusion even further and possibly allow the identification of additional organic molecules in this spectacular source”, concludes Karl Menten, Director at the MPIfR and Head of its Millimeter and Submillimeter Astronomy research department.

Science paper:

Astronomy & Astrophysics

See the full article here .

five-ways-keep-your-child-safe-school-shootings

Please help promote STEM in your local schools.

Effelsberg Radio Telescope- a radio telescope in the Ahr Hills (part of the Eifel) in Bad Münstereifel(DE)

Effelsberg Radio Telescope- a radio telescope in the Ahr Hills (part of the Eifel) in Bad Münstereifel(DE)

The MPG Institute for Radio Astronomy [MPG Institut für Radioastronomie] (DE) is located in Bonn, Germany. It is one of 80 institutes in the MPG Society.

By combining the already existing radio astronomy faculty of the University of Bonn led by Otto Hachenberg with the new MPG institute the MPG Institute for Radio Astronomy was formed. In 1972 the 100-m radio telescope in Effelsberg was opened. The institute building was enlarged in 1983 and 2002.

The institute was founded in 1966 by the MPG Society as the “MPG Institut für Radioastronomie (MPIfR) (DE)”.

The foundation of the institute was closely linked to plans in the German astronomical community to construct a competitive large radio telescope in (then) West Germany. In 1964, Professors Friedrich Becker, Wolfgang Priester and Otto Hachenberg of the Astronomische Institute der Universität Bonn submitted a proposal to the Stiftung Volkswagenwerk for the construction of a large fully steerable radio telescope.

In the same year the Stiftung Volkswagenwerk approved the funding of the telescope project but with the condition that an organization should be found, which would guarantee the operations. It was clear that the operation of such a large instrument was well beyond the possibilities of a single university institute.

Already in 1965 the MPG Society decided in principle to found the MPG Institut für Radioastronomie. Eventually, after a series of discussions, the institute was officially founded in 1966.

MPG Society for the Advancement of Science [MPG Gesellschaft zur Förderung der Wissenschaften e. V.] is a formally independent non-governmental and non-profit association of German research institutes founded in 1911 as the Kaiser Wilhelm Society and renamed the Max Planck Society in 1948 in honor of its former president, theoretical physicist Max Planck. The society is funded by the federal and state governments of Germany as well as other sources.

According to its primary goal, the MPG Society supports fundamental research in the natural, life and social sciences, the arts and humanities in its 83 (as of January 2014) MPG Institutes. The society has a total staff of approximately 17,000 permanent employees, including 5,470 scientists, plus around 4,600 non-tenured scientists and guests. Society budget for 2015 was about €1.7 billion.

The MPG Institutes focus on excellence in research. The MPG Society has a world-leading reputation as a science and technology research organization, with 33 Nobel Prizes awarded to their scientists, and is generally regarded as the foremost basic research organization in Europe and the world. In 2013, the Nature Publishing Index placed the MPG institutes fifth worldwide in terms of research published in Nature journals (after Harvard University, The Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Stanford University and The National Institutes of Health). In terms of total research volume (unweighted by citations or impact), the Max Planck Society is only outranked by The Chinese Academy of Sciences [中国科学院](CN), The Russian Academy of Sciences [Росси́йская акаде́мия нау́к](RU) and Harvard University. The Thomson Reuters-Science Watch website placed the MPG Society as the second leading research organization worldwide following Harvard University, in terms of the impact of the produced research over science fields.

The MPG Society and its predecessor Kaiser Wilhelm Society hosted several renowned scientists in their fields, including Otto Hahn, Werner Heisenberg, and Albert Einstein.

History

The organization was established in 1911 as the Kaiser Wilhelm Society, or Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gesellschaft (KWG), a non-governmental research organization named for the then German emperor. The KWG was one of the world’s leading research organizations; its board of directors included scientists like Walther Bothe, Peter Debye, Albert Einstein, and Fritz Haber. In 1946, Otto Hahn assumed the position of President of KWG, and in 1948, the society was renamed the Max Planck Society (MPG) after its former President (1930–37) Max Planck, who died in 1947.

The MPG Society has a world-leading reputation as a science and technology research organization. In 2006, the Times Higher Education Supplement rankings of non-university research institutions (based on international peer review by academics) placed the MPG Society as No.1 in the world for science research, and No.3 in technology research (behind AT&T Corporation and The DOE’s Argonne National Laboratory.

The domain mpg.de attracted at least 1.7 million visitors annually by 2008 according to a Compete.com study.

MPG Institutes and research groups

The MPG Society consists of over 80 research institutes. In addition, the society funds a number of Max Planck Research Groups (MPRG) and International Max Planck Research Schools (IMPRS). The purpose of establishing independent research groups at various universities is to strengthen the required networking between universities and institutes of the Max Planck Society.

The research units are primarily located across Europe with a few in South Korea and the U.S. In 2007, the Society established its first non-European centre, with an institute on the Jupiter campus of Florida Atlantic University (US) focusing on neuroscience.

The MPG Institutes operate independently from, though in close cooperation with, the universities, and focus on innovative research which does not fit into the university structure due to their interdisciplinary or transdisciplinary nature or which require resources that cannot be met by the state universities.

Internally, MPG Institutes are organized into research departments headed by directors such that each MPI has several directors, a position roughly comparable to anything from full professor to department head at a university. Other core members include Junior and Senior Research Fellows.

In addition, there are several associated institutes:

International Max Planck Research Schools

Together with the Association of Universities and other Education Institutions in Germany, the Max Planck Society established numerous International Max Planck Research Schools (IMPRS) to promote junior scientists:

• Cologne Graduate School of Ageing Research, Cologne

• International Max Planck Research School for Intelligent Systems, at the Max Planck Institute for Intelligent Systems located in Tübingen and Stuttgart

• International Max Planck Research School on Adapting Behavior in a Fundamentally Uncertain World (Uncertainty School), at the Max Planck Institutes for Economics, for Human Development, and/or Research on Collective Goods

• International Max Planck Research School for Analysis, Design and Optimization in Chemical and Biochemical Process Engineering, Magdeburg

• International Max Planck Research School for Astronomy and Cosmic Physics, Heidelberg at the MPI for Astronomy

• International Max Planck Research School for Astrophysics, Garching at the MPI for Astrophysics

• International Max Planck Research School for Complex Surfaces in Material Sciences, Berlin

• International Max Planck Research School for Computer Science, Saarbrücken

• International Max Planck Research School for Earth System Modeling, Hamburg

• International Max Planck Research School for Elementary Particle Physics, Munich, at the MPI for Physics

• International Max Planck Research School for Environmental, Cellular and Molecular Microbiology, Marburg at the Max Planck Institute for Terrestrial Microbiology

• International Max Planck Research School for Evolutionary Biology, Plön at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Biology

• International Max Planck Research School “From Molecules to Organisms”, Tübingen at the Max Planck Institute for Developmental Biology

• International Max Planck Research School for Global Biogeochemical Cycles, Jena at the Max Planck Institute for Biogeochemistry

• International Max Planck Research School on Gravitational Wave Astronomy, Hannover and Potsdam MPI for Gravitational Physics

• International Max Planck Research School for Heart and Lung Research, Bad Nauheim at the Max Planck Institute for Heart and Lung Research

• International Max Planck Research School for Infectious Diseases and Immunity, Berlin at the Max Planck Institute for Infection Biology

• International Max Planck Research School for Language Sciences, Nijmegen

• International Max Planck Research School for Neurosciences, Göttingen

• International Max Planck Research School for Cognitive and Systems Neuroscience, Tübingen

• International Max Planck Research School for Marine Microbiology (MarMic), joint program of the Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology in Bremen, the University of Bremen, the Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research in Bremerhaven, and the Jacobs University Bremen

• International Max Planck Research School for Maritime Affairs, Hamburg

• International Max Planck Research School for Molecular and Cellular Biology, Freiburg

• International Max Planck Research School for Molecular and Cellular Life Sciences, Munich

• International Max Planck Research School for Molecular Biology, Göttingen

• International Max Planck Research School for Molecular Cell Biology and Bioengineering, Dresden

• International Max Planck Research School Molecular Biomedicine, program combined with the ‘Graduate Programm Cell Dynamics And Disease’ at the University of Münster and the Max Planck Institute for Molecular Biomedicine

• International Max Planck Research School on Multiscale Bio-Systems, Potsdam

• International Max Planck Research School for Organismal Biology, at the University of Konstanz and the Max Planck Institute for Ornithology

• International Max Planck Research School on Reactive Structure Analysis for Chemical Reactions (IMPRS RECHARGE), Mülheim an der Ruhr, at the Max Planck Institute for Chemical Energy Conversion

• International Max Planck Research School for Science and Technology of Nano-Systems, Halle at Max Planck Institute of Microstructure Physics

• International Max Planck Research School for Solar System Science at the University of Göttingen hosted by MPI for Solar System Research

• International Max Planck Research School for Astronomy and Astrophysics, Bonn, at the MPI for Radio Astronomy (formerly the International Max Planck Research School for Radio and Infrared Astronomy)

• International Max Planck Research School for the Social and Political Constitution of the Economy, Cologne

• International Max Planck Research School for Surface and Interface Engineering in Advanced Materials, Düsseldorf at Max Planck Institute for Iron Research GmbH

• International Max Planck Research School for Ultrafast Imaging and Structural Dynamics, Hamburg

Max Planck Schools

• Max Planck School of Cognition

• Max Planck School Matter to Life

• Max Planck School of Photonics

Max Planck Center

• The Max Planck Centre for Attosecond Science (MPC-AS), POSTECH Pohang

• The Max Planck POSTECH Center for Complex Phase Materials, POSTECH Pohang

Max Planck Institutes

Among others:

• Max Planck Institute for Neurobiology of Behavior – caesar, Bonn

• Max Planck Institute for Aeronomics in Katlenburg-Lindau was renamed to Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research in 2004;

• Max Planck Institute for Biology in Tübingen was closed in 2005;

• Max Planck Institute for Cell Biology in Ladenburg b. Heidelberg was closed in 2003;

• Max Planck Institute for Economics in Jena was renamed to the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in 2014;

• Max Planck Institute for Ionospheric Research in Katlenburg-Lindau was renamed to Max Planck Institute for Aeronomics in 1958;

• Max Planck Institute for Metals Research, Stuttgart

• Max Planck Institute of Oceanic Biology in Wilhelmshaven was renamed to Max Planck Institute of Cell Biology in 1968 and moved to Ladenburg 1977;

• Max Planck Institute for Psychological Research in Munich merged into the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences in 2004;

• Max Planck Institute for Protein and Leather Research in Regensburg moved to Munich 1957 and was united with the Max Planck Institute for Biochemistry in 1977;

• Max Planck Institute for Virus Research in Tübingen was renamed as Max Planck Institute for Developmental Biology in 1985;

• Max Planck Institute for the Study of the Scientific-Technical World in Starnberg (from 1970 until 1981 (closed)) directed by Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker and Jürgen Habermas.

• Max Planck Institute for Behavioral Physiology

• Max Planck Institute of Experimental Endocrinology

• Max Planck Institute for Foreign and International Social Law

• Max Planck Institute for Physics and Astrophysics

• Max Planck Research Unit for Enzymology of Protein Folding

• Max Planck Institute for Biology of Ageing