1.10.24

Morgan Kelly

Managers and engineers with the California Department of Water Resources conduct the first snow survey of the year in the Sierra Nevada, about 20 miles south of Lake Tahoe, on Jan. 2. (Photo by Andrew Nixon/California Department of Water Resources via AP)

Snow is one of the most contradictory cues we have for understanding climate change.

As in many recent winters, the lack of snowfall in December seemed to preview our global warming future, with peaks from Oregon to New Hampshire more brown than white and the American Southwest facing a severe snow drought.

On the other hand, January has brought some heavy snow to New England, and record blizzards in early 2023 buried California mountain communities, replenished parched reservoirs, and dropped 11 feet of snow on northern Arizona, defying our conceptions of life on a warming planet.

Similarly, scientific data from ground observations, satellites, and climate models do not agree on whether global warming is consistently chipping away at the snowpacks that accumulate in high-elevation mountains and provide water when they melt in spring, complicating efforts to manage the water scarcity that would result for many population centers.

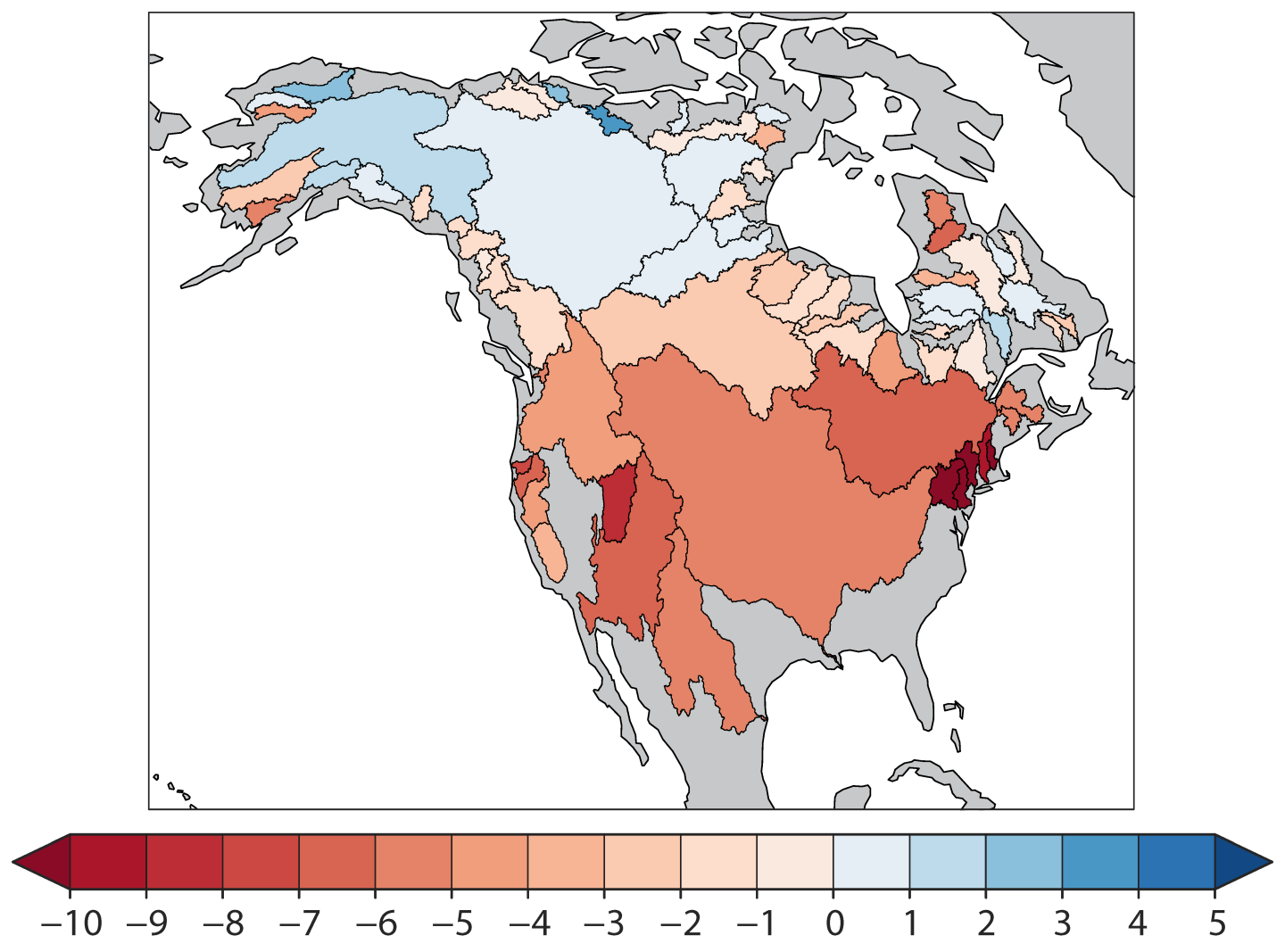

Now, a new Dartmouth study [Nature] cuts through the uncertainty in these observations and provides evidence that seasonal snowpacks throughout most of the Northern Hemisphere have indeed shrunk significantly over the past 40 years due to human-driven climate change. The sharpest global warming-related reductions in snowpack—between 10% to 20% per decade—are in the Southwestern and Northeastern United States, as well as in Central and Eastern Europe.

The Southwest and Northeast saw the greatest loss in spring snowpack between 1981 and 2020, raising concerns about water scarcity and economies reliant on winter recreation. The numbers at bottom correspond to the percentage of spring snowpack lost (red) or gained (blue) per decade, with losses concentrated in populated regions. (Image by Justin Mankin and Alexander Gottlieb)

Researchers Alexander Gottlieb and Justin Mankin report in the journal Nature that the extent and speed of this loss potentially puts the hundreds of millions of people in North America, Europe, and Asia who depend on snow for their water on the precipice of a crisis that continued warming will amplify.

“We were most concerned with how warming is affecting the amount of water stored in snow. The loss of that reservoir is the most immediate and potent risk that climate change poses to society in terms of diminishing snowfall and accumulation,” says Gottlieb, the study’s first author and a Guarini School of Graduate and Advanced Studies PhD candidate in Mankin’s research group and the Ecology, Evolution, Environment and Society graduate program.

“Our work identifies the watersheds that have experienced historical snow loss and those that will be most vulnerable to rapid snowpack declines with further warming,” Gottlieb says. “The train has left the station for regions such as the Southwestern and Northeastern United States. By the end of the 21st century, we expect these places to be close to snow-free by the end of March. We’re on that path and not particularly well adapted when it comes to water scarcity.”

Water security is only one dimension of snow loss, says Mankin, an associate professor of geography and the paper’s senior author.

The Hudson, Susquehanna, Delaware, Connecticut, and Merrimack watersheds in the Northeastern U.S., where water scarcity is not as dire, experienced among the steepest declines in snowpack. But these heavy losses threaten economies in states such as Vermont, New York, and New Hampshire that depend on winter recreation, Mankin says—even machine-made snow has a temperature threshold many areas are fast approaching.

“The recreational implications are emblematic of the ways in which global warming disproportionately affects the most vulnerable communities,” he says. “Ski resorts at lower elevations and latitudes have already been contending with year-on-year snow loss. This will just accelerate, making the business model inviable.”

“We’ll likely see further consolidation of skiing into large, well-resourced resorts at the expense of small and medium-sized ski areas that have such crucial local economic and cultural values. It will be a loss that will ripple through communities,” Mankin says.

In the study, Gottlieb and Mankin focused on how global warming’s influence on temperature and precipitation drove changes in snowpack in 169 river basins across the Northern Hemisphere from 1981 through 2020. The loss of snowpacks potentially means less meltwater in spring for rivers, streams, and soils downstream when ecosystems and people demand water.

Gottlieb and Mankin programmed a machine learning model to examine thousands of observations and climate-model experiments that captured snowpack, temperature, precipitation, and runoff data for Northern Hemisphere watersheds.

This not only let them identify where snowpack losses occurred due to warming, it also gave them the ability to examine the counteracting influence of climate-driven changes in temperature and precipitation, which decrease and increase snowpack thickness, respectively.

The researchers identified the uncertainties that the models and observations shared so they could home in on what scientists had previously missed when gauging the effect of climate change on snow. A 2021 study by Gottlieb and Mankin [Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society] similarly leveraged uncertainties in how scientists measure snow depth and define snow drought to improve predictions of water availability.

Snow comes with uncertainties that have masked the effects of global warming, Mankin says. “People assume that snow is easy to measure, that it simply declines with warming, and that its loss implies the same impacts everywhere. None of these are the case,” he says.

“Snow observations are tricky at the regional scales most relevant for assessing water security,” Mankin says. “Snow is very sensitive to within-winter variations in temperature and precipitation, and the risks from snow loss are not the same in New England as in the Southwest, or for a village in the Alps as in high-mountain Asia.”

Gottlieb and Mankin in fact found that 80% of the Northern Hemisphere’s snowpacks—which are in its far-northern and high-elevation reaches—experienced minimal losses. Snowpacks actually expanded in vast swaths of Alaska, Canada, and Central Asia as climate change increased the precipitation that falls as snow in these frigid regions.

But it is the remaining 20% of the snowpack that exists around—and provides water for—many of the hemisphere’s major population centers that has diminished. Since 1981, documented declines in snowpack for these regions have been largely inconsistent due to the uncertainty in observations and naturally occurring variations in climate.

But Gottlieb and Mankin found that a steady pattern of annual declines in snow accumulation emerge quickly—and leave population centers suddenly and chronically short on new supplies of water from snowmelt.

Many snow-dependent watersheds now find themselves dangerously near a temperature threshold Gottlieb and Mankin call a “snow-loss cliff.” This means that as average winter temperatures in a watershed increase beyond 17 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 8 degrees Celsius), snow loss accelerates even with only modest increases in local average temperatures.

Many highly populated watersheds that rely on snow for water supply are going to see accelerating losses over the next few decades, Mankin says.

“It means that water managers who rely on snowmelt can’t wait for all the observations to agree on snow loss before they prepare for permanent changes to water supplies. By then, it’s too late,” he says. “Once a basin has fallen off that cliff, it’s no longer about managing a short-term emergency until the next big snow. Instead, they will be adapting to permanent changes to water availability.”

See the full article here .

Comments are invited and will be appreciated, especially if the reader finds any errors which I can correct. Use “Reply”.

five-ways-keep-your-child-safe-school-shootings

Please help promote STEM in your local schools.

Dartmouth College is a private Ivy League research university in Hanover, New Hampshire. Established in 1769 by Eleazar Wheelock, Dartmouth is one of the nine colonial colleges chartered before the American Revolution and among the most prestigious in the United States. Although founded to educate Native Americans in Christian theology and the English way of life, the university primarily trained Congregationalist ministers during its early history before it gradually secularized, emerging at the turn of the 20th century from relative obscurity into national prominence.

Following a liberal arts curriculum, Dartmouth provides undergraduate instruction in 40 academic departments and interdisciplinary programs, including 60 majors in the humanities, social sciences, natural sciences, and engineering, and enables students to design specialized concentrations or engage in dual degree programs. In addition to the undergraduate faculty of arts and sciences, Dartmouth has four professional and graduate schools: the Geisel School of Medicine, the Thayer School of Engineering, the Tuck School of Business, and the Guarini School of Graduate and Advanced Studies. The university also has affiliations with the Dartmouth–Hitchcock Medical Center. Dartmouth is home to the Rockefeller Center for Public Policy and the Social Sciences, the Hood Museum of Art, the John Sloan Dickey Center for International Understanding, and the Hopkins Center for the Arts. With a student enrollment of about 6,700, Dartmouth is the smallest university in the Ivy League. Undergraduate admissions are highly selective with an acceptance rate of 6.24% for the class of 2026, including a 4.7% rate for regular decision applicants.

Situated on a terrace above the Connecticut River, Dartmouth’s 269-acre (109 ha) main campus is in the rural Upper Valley region of New England. The university functions on a quarter system, operating year-round on four ten-week academic terms. Dartmouth is known for its strong undergraduate focus, Greek culture, and wide array of enduring campus traditions. Its 34 varsity sports teams compete intercollegiately in the Ivy League conference of the NCAA Division I.

Dartmouth is consistently cited as a leading university for undergraduate teaching by U.S. News & World Report. The Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education listed Dartmouth as the only majority-undergraduate, arts-and-sciences focused, doctoral university in the country that has “some graduate coexistence” and “very high research activity”.

The university has many prominent alumni, including many members of the U.S. Senate and the U.S. House of Representatives, U.S. governors, billionaires, U.S. Cabinet secretaries, Nobel Prize laureates, U.S. Supreme Court justices, and a U.S. vice president. Other notable alumni include Rhodes Scholars, Marshall Scholarship recipients, and Pulitzer Prize winners. Dartmouth alumni also include many CEOs and founders of Fortune 500 corporations, high-ranking U.S. diplomats, academic scholars, literary and media figures, professional athletes, and Olympic medalists.

Comprising a small undergraduate population and total student enrollment, Dartmouth is the smallest university in the Ivy League. Its undergraduate program is characterized by the Carnegie Foundation and U.S. News & World Report as “most selective”. Dartmouth offers a broad range of academic departments, an extensive research enterprise, numerous community outreach and public service programs, and the highest rate of study abroad participation in the Ivy League.

Dartmouth, a liberal arts institution, offers a four-year Bachelor of Arts and ABET-accredited Bachelor of Engineering degree to undergraduate students. The college has 39 academic departments offering 56 major programs, while students are free to design special majors or engage in dual majors. The most popular majors: economics, government, computer science, engineering sciences, and history. The Economics Department also holds the distinction as the top-ranked bachelor’s-only economics program in the world.

In order to graduate, a student must complete 35 total courses, eight to ten of which are typically part of a chosen major program. Other requirements for graduation include the completion of ten “distributive requirements” in a variety of academic fields, proficiency in a foreign language, and completion of a writing class and first-year seminar in writing. Many departments offer honors programs requiring students seeking that distinction to engage in “independent, sustained work”, culminating in the production of a thesis. In addition to the courses offered in Hanover, Dartmouth offers 57 different off-campus programs, including Foreign Study Programs, Language Study Abroad programs, and Exchange Programs.

Through the Graduate Studies program, Dartmouth grants doctorate and master’s degrees in 19 Arts & Sciences graduate programs. Although the first graduate degree, a PhD in classics, was awarded in 1885, many of the current PhD programs have only existed since the 1960s. Furthermore, Dartmouth is home to three professional schools: the Geisel School of Medicine (established 1797), Thayer School of Engineering (1867)—which also serves as the undergraduate department of engineering sciences—and Tuck School of Business (1900). With these professional schools and graduate programs, conventional American usage would accord Dartmouth the label of “Dartmouth University”; however, because of historical and nostalgic reasons (such as Dartmouth College v. Woodward), the school uses the name “Dartmouth College” to refer to the entire institution.

Dartmouth employs a large number of tenured or tenure-track faculty members, including the highest proportion of female tenured professors among the Ivy League universities, and the first black woman tenure-track faculty member in computer science at an Ivy League university. Faculty members have been at the forefront of such major academic developments as the Dartmouth Workshop, the Dartmouth Time Sharing System, Dartmouth BASIC, and Dartmouth ALGOL 30. Sponsored project awards to Dartmouth faculty research amoun to $200 million.

Dartmouth serves as the host institution of the University Press of New England, a university press founded in 1970 that is supported by a consortium of schools that also includes Brandeis University, The University of New Hampshire, Northeastern University, Tufts University and The University of Vermont.

Rankings

Dartmouth ranks very highly among undergraduate programs at national universities by U.S. News & World Report. U.S. News also ranks the school very highly for veterans, very highly for undergraduate teaching, and for “best value” at national universities. Dartmouth’s undergraduate teaching was previously ranked very highly by U.S. News. Dartmouth College is accredited by The New England Commission of Higher Education.

In Forbes’ rankings of 650 universities, liberal arts colleges and service academies, Dartmouth ranks very highly overall and in research universities. In the Forbes “grateful graduate” rankings, Dartmouth comes very highly.

The Academic Ranking of World Universities ranked Dartmouth very highly among the best universities in the nation. However, this specific ranking has drawn criticism from scholars for not adequately adjusting for the size of an institution, which leads to larger institutions ranking above smaller ones like Dartmouth. Dartmouth’s small size and its undergraduate focus also disadvantage its ranking in other international rankings because ranking formulas favor institutions with a large number of graduate students.

The Carnegie Foundation classification listed Dartmouth as the only “majority-undergraduate”, “arts-and-sciences focus[ed]”, “research university” in the country that also had “some graduate coexistence” and “very high research activity”.

The Dartmouth Plan

Dartmouth functions on a quarter system, operating year-round on four ten-week academic terms. The Dartmouth Plan (or simply “D-Plan”) is an academic scheduling system that permits the customization of each student’s academic year. All undergraduates are required to be in residence for the fall, winter, and spring terms of their freshman and senior years, as well as the summer term of their sophomore year. However, students may petition to alter this plan so that they may be off during their freshman, senior, or sophomore summer terms. During all terms, students are permitted to choose between studying on-campus, studying at an off-campus program, or taking a term off for vacation, outside internships, or research projects. The typical course load is three classes per term, and students will generally enroll in classes for 12 total terms over the course of their academic career.

The D-Plan was instituted in the early 1970s at the same time that Dartmouth began accepting female undergraduates. It was initially devised as a plan to increase the enrollment without enlarging campus accommodations, and has been described as “a way to put 4,000 students into 3,000 beds”. Although new dormitories have been built since, the number of students has also increased and the D-Plan remains in effect. It was modified in the 1980s in an attempt to reduce the problems of lack of social and academic continuity.