From The Scripps Institution of Oceanography

at

The University of California-San Diego

3.2.23

Robert Monroe

scrippsnews@ucsd.edu

Polluted waters off Imperial Beach. Photo: WILDCOAST

New research led by Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC San Diego has confirmed that coastal water pollution transfers to the atmosphere in sea spray aerosol, which can reach people beyond just beachgoers, surfers, and swimmers.

Rainfall in the US-Mexico border region causes complications for wastewater treatment and results in untreated sewage being diverted into the Tijuana River and flowing into the ocean in south Imperial Beach. This input of contaminated water has caused chronic coastal water pollution in Imperial Beach for decades. New research shows that sewage-polluted coastal waters transfer to the atmosphere in sea spray aerosol formed by breaking waves and bursting bubbles. Sea spray aerosol contains bacteria, viruses, and chemical compounds from the seawater.

The researchers report their findings March 2 in the journal Environmental Science & Technology [below]. The study appears in the midst of a winter in which an estimated 13 billion gallons of sewage-polluted waters have entered the ocean via the Tijuana River since Dec. 28, 2022, according to lead researcher Kim Prather, a Distinguished Chair in Atmospheric Chemistry, and Distinguished Professor at Scripps Oceanography and UC San Diego’s Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry. She also serves as the founding director of the NSF Center for Aerosol Impacts on Chemistry of the Environment (CAICE).

“We’ve shown that up to three-quarters of the bacteria that you breathe in at Imperial Beach are coming from aerosolization of raw sewage in the surf zone,” said Prather. “Coastal water pollution has been traditionally considered just a waterborne problem. People worry about swimming and surfing in it but not about breathing it in, even though the aerosols can travel long distances and expose many more people than those just at the beach or in the water.”

Aerosol filter sampling downwind of polluted coastal waters in Imperial Beach. Photo: Matthew Pendergraft.

The team sampled coastal aerosols at Imperial Beach and water from the Tijuana River between January and May 2019. Then they used DNA sequencing and mass spectrometry to link bacteria and chemical compounds in coastal aerosol back to the sewage-polluted Tijuana River flowing into coastal waters. Aerosols from the ocean were found to contain bacteria and chemicals originating from the Tijuana River. Now the team is conducting follow-up research attempting to detect viruses and other airborne pathogens.

Prather and colleagues caution that the work does not mean people are getting sick from sewage in sea spray aerosol. Most bacteria and viruses are harmless and the presence of bacteria in sea spray aerosol does not automatically mean that microbes – pathogenic or otherwise – become airborne. Infectivity, exposure levels, and other factors that determine risk need further investigation, the authors said.

This study involved a collaboration among three different research groups – led by Prather in collaboration with UC San Diego School of Medicine and Jacobs School of Engineering researcher Rob Knight, and Pieter Dorrestein of the UC San Diego Skaggs School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Science, both affiliated with the Department of Pediatrics – to study the potential links between bacteria and chemicals in sea spray aerosol with sewage in the Tijuana River.

“This research demonstrates that coastal communities are exposed to coastal water pollution even without entering polluted waters,” said lead author Matthew Pendergraft, a recent graduate from Scripps Oceanography who obtained his PhD under the guidance of Prather. “More research is necessary to determine the level of risk posed to the public by aerosolized coastal water pollution. These findings provide further justification for prioritizing cleaning up coastal waters.”

Additional funding to further investigate the conditions that lead to aerosolization of pollutants and pathogens, how far they travel, and potential public health ramifications has been secured by Congressman Scott Peters (CA-50) in the Fiscal Year (FY) 2023 Omnibus spending bill.

Besides Prather, Pendergraft, Knight and Dorrestein, the research team included Daniel Petras and Clare Morris from Scripps Oceanography; Pedro Beldá-Ferre, MacKenzie Bryant, Tara Schwartz, Gail Ackermann, and Greg Humphrey from the UC San Diego School of Medicine; Brock Mitts from UC San Diego’s Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry; Allegra Aron from the UC San Diego Skaggs School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Science; and independent researcher Ethan Kaandorp. The study was funded by UC San Diego’s Understanding and Protecting the Planet (UPP) initiative and the German Research Foundation.

Environmental Science & Technology

Figure 1. Site map and sampling locations. Displayed are the locations of aerosol and water sampling at IB, CA, USA (bottom) and 35 km away at SIO in La Jolla, CA, USA (top). Marker formatting is consistent in all figures. The dashed line denotes the Mexico–USA border. Sites of water sampling are denoted with a “w”, and sites of aerosol sampling are denoted with an “a”. Produced using MATLAB version 9.10.0.1602886 (R2021a). (37) Map imagery reprinted with permission from Earthstar Geographics. Copyright 2022 Earthstar Geographics/Terracolor.

Figure 2. RPCA and aerosol source apportionment from the bacteria community and chemical composition. (A,B) shows RPCA (Aitchison distances) of non-targeted mass spectrometry (A) and 16S data (B). (C,D) presents ST2 results─the fractional contributions of different sources to each aerosol sample─for non-targeted mass spectrometry (C) and 16S data (D). Each bar represents one aerosol sample and is composed of the fractional contribution of molecules (C) or bacteria (D) from TJRw (blue), IBPw (orange), SIOPw (brown), and Unknown (gray) as determined by ST2. Bars align vertically between (C) and (D) and are for the same aerosol sample.

For further illustrations see the science paper.

See the full article here .

Comments are invited and will be appreciated, especially if the reader finds any errors which I can correct. Use “Reply”.

five-ways-keep-your-child-safe-school-shootings

Please help promote STEM in your local schools.

A department of The University of California-San Diego, The Scripps Institution of Oceanography is one of the oldest, largest, and most important centers for ocean, earth and atmospheric science research, education, and public service in the world.

Research at Scripps encompasses physical, chemical, biological, geological, and geophysical studies of the oceans, Earth, and planets. Scripps undergraduate and graduate programs provide transformative educational and research opportunities in ocean, earth, and atmospheric sciences, as well as degrees in climate science and policy and marine biodiversity and conservation.

Scripps Institution of Oceanography was founded in 1903 as the Marine Biological Association of San Diego, an independent biological research laboratory. It was proposed and incorporated by a committee of the San Diego Chamber of Commerce, led by local activist and amateur malacologist Fred Baker, together with two colleagues. He recruited University of California Zoology professor William Emerson Ritter to head up the proposed marine biology institution, and obtained financial support from local philanthropists E. W. Scripps and his sister Ellen Browning Scripps. They fully funded the institution for its first decade. It began institutional life in the boathouse of the Hotel del Coronado located on San Diego Bay. It re-located in 1905 to the La Jolla area on the head above La Jolla Cove, and finally in 1907 to its present location.

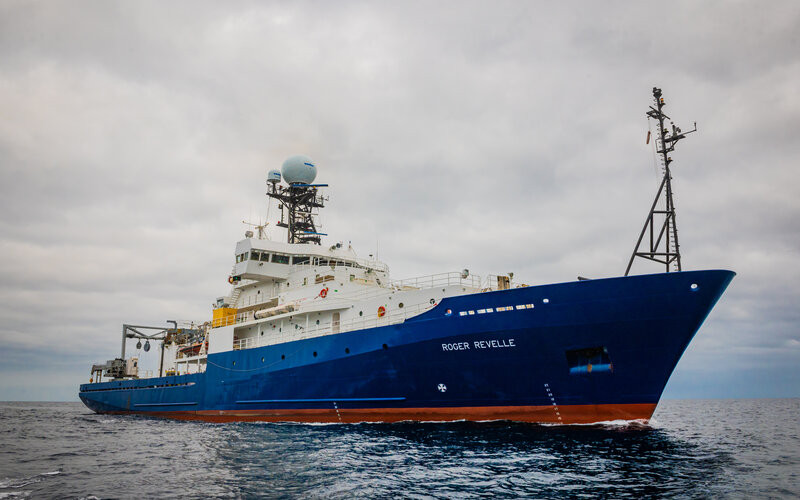

In 1912 Scripps became incorporated into The University of California and was renamed the “Scripps Institution for Biological Research.” Since 1916, measurements have been taken daily at its pier. The name was changed to Scripps Institution of Oceanography in October 1925. During the 1960s, led by Scripps Institution of Oceanography director Roger Revelle, it formed the nucleus for the creation of The University of California-San Diego on a bluff overlooking Scripps Institution.

The Old Scripps Building, designed by Irving Gill, was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1982. Architect Barton Myers designed the current Scripps Building for the Institution of Oceanography in 1998.

Research programs

The institution’s research programs encompass biological, physical, chemical, geological, and geophysical studies of the oceans and land. Scripps also studies the interaction of the oceans with both the atmospheric climate and environmental concerns on terra firma. Related to this research, Scripps offers undergraduate and graduate degrees.

Today, the Scripps staff of 1,300 includes approximately 235 faculty, 180 other scientists and some 350 graduate students, with an annual budget of more than $281 million. The institution operates a fleet of four oceanographic research vessels.

The Integrated Research Themes encompassing the work done by Scripps researchers are Biodiversity and Conservation, California Environment, Earth and Planetary Chemistry, Earth Through Space and Time, Energy and the Environment, Environment and Human Health, Global Change, Global Environmental Monitoring, Hazards, Ice and Climate, Instruments and Innovation, Interfaces, Marine Life, Modeling Theory and Computing, Sound and Light and the Sea, and Waves and Circulation.

Organizational structure

Scripps Oceanography is divided into three research sections, each with its own subdivisions:

• Biology

o Center for Marine Biotechnology & Biomedicine (CMBB).

o Integrative Oceanography Division (IOD) Archived 2015-11-29 at the Wayback Machine.

o Marine Biology Research Division (MBRD).

• Earth

o Cecil H. and Ida M. Green Institute of Geophysics and Planetary Physics (IGPP).

o Geosciences Research Division (GRD).

• Oceans & Atmosphere

o Climate, Atmospheric Science & Physical Oceanography (CASPO).

o Marine Physical Laboratory (MPL) Archived 2013-10-04 at the Wayback Machine.

The University of California-San Diego is a public land-grant research university in San Diego, California. Established in 1960 near the pre-existing Scripps Institution of Oceanography, The University of California-San Diego is the southernmost of the ten campuses of the University of California, and offers over 200 undergraduate and graduate degree programs, enrolling 33,343 undergraduate and 9,533 graduate students. The University of California-San Diego occupies 2,178 acres (881 ha) near the coast of the Pacific Ocean, with the main campus resting on approximately 1,152 acres (466 ha). The University of California-San Diego is ranked among the best universities in the world by major college and university rankings.

The University of California-San Diego consists of twelve undergraduate, graduate and professional schools as well as seven undergraduate residential colleges. It received over 140,000 applications for undergraduate admissions in Fall 2021, making it the second most applied-to university in the United States. The University of California-San Diego San Diego Health, the region’s only academic health system, provides patient care, conducts medical research and educates future health care professionals at The University of California-San Diego Medical Center, Hillcrest, Jacobs Medical Center, Moores Cancer Center, Sulpizio Cardiovascular Center, Shiley Eye Institute, Institute for Genomic Medicine, Koman Family Outpatient Pavilion and various express care and urgent care clinics throughout San Diego.

The University of California-San Diego operates 19 organized research units as well as eight School of Medicine research units, six research centers at Scripps Institution of Oceanography and two multi-campus initiatives. The University of California-San Diego is also closely affiliated with several regional research centers, such as The Salk Institute, the Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Discovery Institute, the Sanford Consortium for Regenerative Medicine, and The Scripps Research Institute. It is classified among “R1: Doctoral Universities – Very high research activity”. According to The National Science Foundation, The University of California-San Diego spent $1.354 billion on research and development in fiscal year 2019, ranking it 6th in the nation.

The University of California-San Diego is considered one of the country’s “Public Ivies”. The University of California-San Diego faculty, researchers, and alumni have won 27 Nobel Prizes as well as three Fields Medals, eight National Medals of Science, eight MacArthur Fellowships, and three Pulitzer Prizes. Additionally, of the current faculty, 29 have been elected to The National Academy of Engineering, 70 to The National Academy of Sciences, 45 to the Institute of Medicine and 110 to The American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

History

When the Regents of the University of California originally authorized The University of California-San Diego campus in 1956, it was planned to be a graduate and research institution, providing instruction in the sciences, mathematics, and engineering. Local citizens supported the idea, voting the same year to transfer to the university 59 acres (24 ha) of mesa land on the coast near the preexisting Scripps Institution of Oceanography. The Regents requested an additional gift of 550 acres (220 ha) of undeveloped mesa land northeast of Scripps, as well as 500 acres (200 ha) on the former site of Camp Matthews from the federal government, but Roger Revelle, then director of Scripps Institution and main advocate for establishing the new campus, jeopardized the site selection by exposing the La Jolla community’s exclusive real estate business practices, which were antagonistic to minority racial and religious groups. This outraged local conservatives, as well as Regent Edwin W. Pauley.

University of California President Clark Kerr satisfied San Diego city donors by changing the proposed name from University of California, La Jolla, to University of California-San Diego. The city voted in agreement to its part in 1958, and the University of California approved construction of the new campus in 1960. Because of the clash with Pauley, Revelle was not made chancellor. Herbert York, first director of The DOE’s Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, was designated instead. York planned the main campus according to the “Oxbridge” model, relying on many of Revelle’s ideas.

According to Kerr, “San Diego always asked for the best,” though this created much friction throughout the University of California system, including with Kerr himself, because The University of California-San Diego often seemed to be “asking for too much and too fast.” Kerr attributed The University of California-San Diego’s “special personality” to Scripps, which for over five decades had been the most isolated University of California unit in every sense: geographically, financially, and institutionally. It was a great shock to the Scripps community to learn that Scripps was now expected to become the nucleus of a new University of California campus and would now be the object of far more attention from both the university administration in Berkeley and the state government in Sacramento.

The University of California-San Diego was the first general campus of the University of California to be designed “from the top down” in terms of research emphasis. Local leaders disagreed on whether the new school should be a technical research institute or a more broadly based school that included undergraduates as well. John Jay Hopkins of General Dynamics Corporation pledged one million dollars for the former while the City Council offered free land for the latter. The original authorization for The University of California-San Diego campus given by the University of California Regents in 1956 approved a “graduate program in science and technology” that included undergraduate programs, a compromise that won both the support of General Dynamics and the city voters’ approval.

Nobel laureate Harold Urey, a physicist from the University of Chicago, and Hans Suess, who had published the first paper on the greenhouse effect with Revelle in the previous year, were early recruits to the faculty in 1958. Maria Goeppert-Mayer, later the second female Nobel laureate in physics, was appointed professor of physics in 1960. The graduate division of the school opened in 1960 with 20 faculty in residence, with instruction offered in the fields of physics, biology, chemistry, and earth science. Before the main campus completed construction, classes were held in the Scripps Institution of Oceanography.

By 1963, new facilities on the mesa had been finished for the School of Science and Engineering, and new buildings were under construction for Social Sciences and Humanities. Ten additional faculty in those disciplines were hired, and the whole site was designated the First College, later renamed after Roger Revelle, of the new campus. York resigned as chancellor that year and was replaced by John Semple Galbraith. The undergraduate program accepted its first class of 181 freshman at Revelle College in 1964. Second College was founded in 1964, on the land deeded by the federal government, and named after environmentalist John Muir two years later. The University of California-San Diego School of Medicine also accepted its first students in 1966.

Political theorist Herbert Marcuse joined the faculty in 1965. A champion of the New Left, he reportedly was the first protester to occupy the administration building in a demonstration organized by his student, political activist Angela Davis. The American Legion offered to buy out the remainder of Marcuse’s contract for $20,000; the Regents censured Chancellor William J. McGill for defending Marcuse on the basis of academic freedom, but further action was averted after local leaders expressed support for Marcuse. Further student unrest was felt at the university, as the United States increased its involvement in the Vietnam War during the mid-1960s, when a student raised a Viet Minh flag over the campus. Protests escalated as the war continued and were only exacerbated after the National Guard fired on student protesters at Kent State University in 1970. Over 200 students occupied Urey Hall, with one student setting himself on fire in protest of the war.

Early research activity and faculty quality, notably in the sciences, was integral to shaping the focus and culture of the university. Even before The University of California-San Diego had its own campus, faculty recruits had already made significant research breakthroughs, such as the Keeling Curve, a graph that plots rapidly increasing carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere and was the first significant evidence for global climate change; the Kohn–Sham equations, used to investigate particular atoms and molecules in quantum chemistry; and the Miller–Urey experiment, which gave birth to the field of prebiotic chemistry.

Engineering, particularly computer science, became an important part of the university’s academics as it matured. University researchers helped develop The University of California-San Diego Pascal, an early machine-independent programming language that later heavily influenced Java; the National Science Foundation Network, a precursor to the Internet; and the Network News Transfer Protocol during the late 1970s to 1980s. In economics, the methods for analyzing economic time series with time-varying volatility (ARCH), and with common trends (co-integration) were developed. The University of California-San Diego maintained its research intense character after its founding, racking up 25 Nobel Laureates affiliated within 50 years of history; a rate of five per decade.

Under Richard C. Atkinson’s leadership as chancellor from 1980 to 1995, The University of California-San Diego strengthened its ties with the city of San Diego by encouraging technology transfer with developing companies, transforming San Diego into a world leader in technology-based industries. He oversaw a rapid expansion of the School of Engineering, later renamed after Qualcomm founder Irwin M. Jacobs, with the construction of the San Diego Supercomputer Center and establishment of the computer science, electrical engineering, and bioengineering departments. Private donations increased from $15 million to nearly $50 million annually, faculty expanded by nearly 50%, and enrollment doubled to about 18,000 students during his administration. By the end of his chancellorship, the quality of The University of California-San Diego graduate programs was ranked 10th in the nation by The National Research Council.

The University of California-San Diego continued to undergo further expansion during the first decade of the new millennium with the establishment and construction of two new professional schools — the Skaggs School of Pharmacy and Rady School of Management—and the California Institute for Telecommunications and Information Technology, a research institute run jointly with University of California-Irvine. The University of California-San Diego also reached two financial milestones during this time, becoming the first university in the western region to raise over $1 billion in its eight-year fundraising campaign in 2007 and also obtaining an additional $1 billion through research contracts and grants in a single fiscal year for the first time in 2010. Despite this, due to the California budget crisis, the university loaned $40 million against its own assets in 2009 to offset a significant reduction in state educational appropriations. The salary of Pradeep Khosla, who became chancellor in 2012, has been the subject of controversy amidst continued budget cuts and tuition increases.

On November 27, 2017, The University of California-San Diego announced it would leave its longtime athletic home of the California Collegiate Athletic Association, an NCAA Division II league, to begin a transition to Division I in 2020. At that time, it would join the Big West Conference, already home to four other UC campuses (Davis, Irvine, Riverside, Santa Barbara). The transition period would run through the 2023–24 school year. The university prepared to transition to NCAA Division I competition on July 1, 2020.

Research

Applied Physics and Mathematics

The Nature Index lists The University of California-San Diego as 6th in the United States for research output by article count in 2019. In 2017, The University of California-San Diego spent $1.13 billion on research, the 7th highest expenditure among academic institutions in the U.S. The university operates several organized research units, including the Center for Astrophysics and Space Sciences (CASS), the Center for Drug Discovery Innovation, and the Institute for Neural Computation. The University of California-San Diego also maintains close ties to the nearby Scripps Research Institute and Salk Institute for Biological Studies. In 1977, The University of California-San Diego developed and released the University of California-San Diego Pascal programming language. The university was designated as one of the original national Alzheimer’s disease research centers in 1984 by the National Institute on Aging. In 2018, The University of California-San Diego received $10.5 million from The DOE’s National Nuclear Security Administration to establish the Center for Matters under Extreme Pressure (CMEC).

The University of California-San Diego founded The San Diego Supercomputer Center in 1985, which provides high performance computing for research in various scientific disciplines. In 2000, The University of California-San Diego partnered with The University of California-Irvine to create the Qualcomm Institute, which integrates research in photonics, nanotechnology, and wireless telecommunication to develop solutions to problems in energy, health, and the environment.

The University of California-San Diego also operates the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, one of the largest centers of research in earth science in the world, which predates the university itself. Together, SDSC and SIO, along with funding partner universities California Institute of Technology, San Diego State University, and The University of California-Santa Barbara, manage the High Performance Wireless Research and Education Network.