From The Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics

8.10.23

Peter Edmonds

Interim CfA Public Affairs Officer

Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian

+1 617-571-7279

pedmonds@cfa.harvard.edu

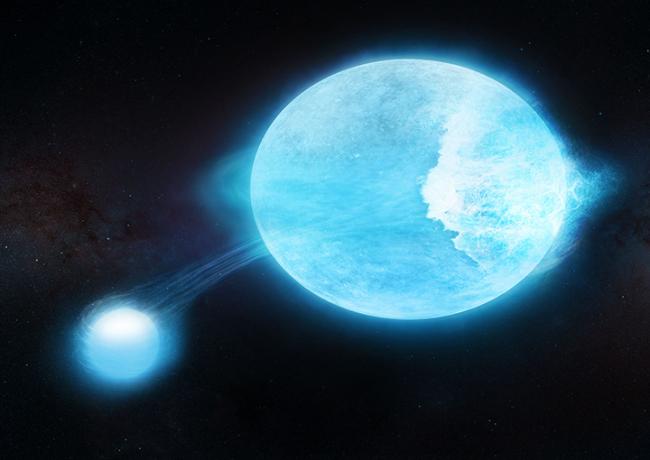

A first-of-its-kind “heartbreak” star, with pulsing brightness changes and breaking surface waves, offers a unique vantage into the evolution of massive double star systems.

Credit: Melissa Weiss, CfA.

The star system intrigued researchers because it is the most dramatic “heartbeat star” on record. Now new models have revealed that titanic waves, generated by tides, are repeatedly breaking on one of the stars in the system—the first time this phenomenon has ever been seen on a star.

“Heartbeat stars” are stars in close pairs that periodically pulse in brightness, like the rhythm of a beating heart on an EKG machine. The stars in heartbeat systems loop through elongated oval orbits. Whenever they swing close together, the stars’ gravities generate tides—just as the Moon creates ocean tides on Earth. The tides stretch and distort the shapes of the stars, altering the amount of starlight seen coming from them as their wide or narrow sides alternately face Earth.

A new study explains why the brightness fluctuations from one particularly extreme heartbeat star system measure some 200 times greater than typical heartbeat stars. The cause: gargantuan waves that roll across the bigger star, kicked up when its smaller companion star regularly makes close passes. These tidal waves attain such towering heights and high speeds, the study finds, that the waves break—similar to ocean waves—and crash down onto the big star’s surface.

Dubbed a “heartbreak star” by astronomers, the system offers an unprecedented look at how massive stars interact.

A gas dynamics computer simulation of the system shows that during a close passage, gas is raised into a huge tidal wave on the larger star before crashing back to the surface. Credit: Morgan MacLeod, CfA.

“Each crash of the star’s towering tidal waves releases enough energy to disintegrate our entire planet several hundred times over,” says Morgan MacLeod, a Postdoctoral Fellow in Theoretical Astrophysics at the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian (CfA) and author of a new study published in Nature Astronomy [below] reporting the findings. “These are really big waves.”

And yet, according to Professor Abraham (Avi) Loeb, MacLeod’s advisor, the Director of the Institute for Theory and Computation at CfA and the paper’s other author, “Breaking waves in stars are as beautiful as those on the beaches of our oceans.”

Heartbeat stars were first seen when NASA’s exoplanet-hunting Kepler space telescope picked out their telltale, usually subtle stellar brightness pulsations.

The extreme heartbreak star, though, is anything but subtle. The larger star in the system is nearly 35 times the mass of the Sun and, together with its smaller companion star, is officially designated MACHO 80.7443.1718 — not because of any stellar brawn, but because the system’s brightness changes were first recorded by the MACHO Project in the 1990s, which sought signs of dark matter in our galaxy.

Most heartbeat stars vary in brightness only by about 0.1%, but MACHO 80.7443.1718 jumped out to astronomers because of its unprecedentedly dramatic brightness swings, up and down by 20%. “We don’t know of any other heartbeat star that varies this wildly,” says MacLeod.

To unravel the mystery, MacLeod created a computer model of MACHO 80.7443.1718. His model captured how the interacting gravity of the two stars generates massive tides in the bigger star. The resulting tidal waves rise to about a fifth of the behemoth star’s radius, which equates to waves about as tall as three Suns stacked on top of each other, or roughly 2.7 million miles high.

The simulations show that the massive waves start out as smooth and organized swells, just like ocean water waves, before curling over on themselves and breaking. As beachgoers know, powerfully crashing ocean waves launch sea spray and bubbles, leaving “a big foamy mess” where there was once a smooth wave, MacLeod says.

The tremendous energy release of the crashing waves on MACHO 80.7443.1718 has two effects, MacLeod’s model shows. It spins the stellar surface faster and faster, and hurls stellar gas outward to form a rotating and glowing stellar atmosphere.

About once a month, the two stars pass each other and a fresh monster wave barrels across the heartbreak star’s surface. Cumulatively, this agitation has caused the big star in MACHO 80.7443.1718 to bulge at its equator by about 50% more than at its poles. And, with each new passing wave, more material is flung outward, like “spinning pizza crust flinging off chunks of cheese and sauce” says MacLeod. The signature glow of this atmosphere was one of the key clues that waves were breaking on the star’s surface, according to MacLeod.

As unprecedented as MACHO 80.7443.1718 is, it is unlikely to be unique. Of the nearly 1,000 heartbeat stars discovered so far, about 20 of them display large brightness fluctuations approaching those of the system simulated by MacLeod and Loeb. “This heartbreak star could just be the first of a growing class of astronomical objects,” MacLeod says. “We’re already planning a search for more heartbreak stars, looking for the glowing atmospheres flung off by their breaking waves.”

All things considered, MacLeod says we are lucky to have caught the star in this phase, “We are watching a brief and transformative moment in a long stellar lifetime.” And by watching the colossal surf roll across a stellar surface, astronomers hope to gain an understanding of how close interactions shape the evolution of stellar pairs.

See the full article here .

Comments are invited and will be appreciated, especially if the reader finds any errors which I can correct. Use “Reply”.

five-ways-keep-your-child-safe-school-shootings

Please help promote STEM in your local schools.

Harvard University is the oldest institution of higher education in the United States, established in 1636 by vote of the Great and General Court of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. It was named after the College’s first benefactor, the young minister John Harvard of Charlestown, who upon his death in 1638 left his library and half his estate to the institution. A statue of John Harvard stands today in front of University Hall in Harvard Yard, and is perhaps the University’s best-known landmark.

Harvard University has 12 degree-granting Schools in addition to the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study. The University has grown from nine students with a single master to an enrollment of more than 20,000 degree candidates including undergraduate, graduate, and professional students. There are more than 360,000 living alumni in the U.S. and over 190 other countries.

The Massachusetts colonial legislature, the General Court, authorized Harvard University’s founding. In its early years, Harvard College primarily trained Congregational and Unitarian clergy, although it has never been formally affiliated with any denomination. Its curriculum and student body were gradually secularized during the 18th century, and by the 19th century, Harvard University (US) had emerged as the central cultural establishment among the Boston elite. Following the American Civil War, President Charles William Eliot’s long tenure (1869–1909) transformed the college and affiliated professional schools into a modern research university; Harvard became a founding member of the Association of American Universities in 1900. James B. Conant led the university through the Great Depression and World War II; he liberalized admissions after the war.

The university is composed of ten academic faculties plus the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study. Arts and Sciences offers study in a wide range of academic disciplines for undergraduates and for graduates, while the other faculties offer only graduate degrees, mostly professional. Harvard has three main campuses: the 209-acre (85 ha) Cambridge campus centered on Harvard Yard; an adjoining campus immediately across the Charles River in the Allston neighborhood of Boston; and the medical campus in Boston’s Longwood Medical Area. Harvard University’s endowment is valued at $41.9 billion, making it the largest of any academic institution. Endowment income helps enable the undergraduate college to admit students regardless of financial need and provide generous financial aid with no loans The Harvard Library is the world’s largest academic library system, comprising 79 individual libraries holding about 20.4 million items.

Harvard University has more alumni, faculty, and researchers who have won Nobel Prizes (161) and Fields Medals (18) than any other university in the world and more alumni who have been members of the U.S. Congress, MacArthur Fellows, Rhodes Scholars (375), and Marshall Scholars (255) than any other university in the United States. Its alumni also include eight U.S. presidents and 188 living billionaires, the most of any university. Fourteen Turing Award laureates have been Harvard affiliates. Students and alumni have also won 10 Academy Awards, 48 Pulitzer Prizes, and 108 Olympic medals (46 gold), and they have founded many notable companies.

Colonial

Harvard University was established in 1636 by vote of the Great and General Court of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. In 1638, it acquired British North America’s first known printing press. In 1639, it was named Harvard College after deceased clergyman John Harvard, an alumnus of the University of Cambridge(UK) who had left the school £779 and his library of some 400 volumes. The charter creating the Harvard Corporation was granted in 1650.

A 1643 publication gave the school’s purpose as “to advance learning and perpetuate it to posterity, dreading to leave an illiterate ministry to the churches when our present ministers shall lie in the dust.” It trained many Puritan ministers in its early years and offered a classic curriculum based on the English university model—many leaders in the colony had attended the University of Cambridge—but conformed to the tenets of Puritanism. Harvard University has never affiliated with any particular denomination, though many of its earliest graduates went on to become clergymen in Congregational and Unitarian churches.

Increase Mather served as president from 1681 to 1701. In 1708, John Leverett became the first president who was not also a clergyman, marking a turning of the college away from Puritanism and toward intellectual independence.

19th century

In the 19th century, Enlightenment ideas of reason and free will were widespread among Congregational ministers, putting those ministers and their congregations in tension with more traditionalist, Calvinist parties. When Hollis Professor of Divinity David Tappan died in 1803 and President Joseph Willard died a year later, a struggle broke out over their replacements. Henry Ware was elected to the Hollis chair in 1805, and the liberal Samuel Webber was appointed to the presidency two years later, signaling the shift from the dominance of traditional ideas at Harvard to the dominance of liberal, Arminian ideas.

Charles William Eliot, president 1869–1909, eliminated the favored position of Christianity from the curriculum while opening it to student self-direction. Though Eliot was the crucial figure in the secularization of American higher education, he was motivated not by a desire to secularize education but by Transcendentalist Unitarian convictions influenced by William Ellery Channing and Ralph Waldo Emerson.

20th century

In the 20th century, Harvard University’s reputation grew as a burgeoning endowment and prominent professors expanded the university’s scope. Rapid enrollment growth continued as new graduate schools were begun and the undergraduate college expanded. Radcliffe College, established in 1879 as the female counterpart of Harvard College, became one of the most prominent schools for women in the United States. Harvard University became a founding member of the Association of American Universities in 1900.

The student body in the early decades of the century was predominantly “old-stock, high-status Protestants, especially Episcopalians, Congregationalists, and Presbyterians.” A 1923 proposal by President A. Lawrence Lowell that Jews be limited to 15% of undergraduates was rejected, but Lowell did ban blacks from freshman dormitories.

President James B. Conant reinvigorated creative scholarship to guarantee Harvard University’s preeminence among research institutions. He saw higher education as a vehicle of opportunity for the talented rather than an entitlement for the wealthy, so Conant devised programs to identify, recruit, and support talented youth. In 1943, he asked the faculty to make a definitive statement about what general education ought to be, at the secondary as well as at the college level. The resulting Report, published in 1945, was one of the most influential manifestos in 20th century American education.

Between 1945 and 1960, admissions were opened up to bring in a more diverse group of students. No longer drawing mostly from select New England prep schools, the undergraduate college became accessible to striving middle class students from public schools; many more Jews and Catholics were admitted, but few blacks, Hispanics, or Asians. Throughout the rest of the 20th century, Harvard became more diverse.

Harvard University’s graduate schools began admitting women in small numbers in the late 19th century. During World War II, students at Radcliffe College (which since 1879 had been paying Harvard University professors to repeat their lectures for women) began attending Harvard University classes alongside men. Women were first admitted to the medical school in 1945. Since 1971, Harvard University has controlled essentially all aspects of undergraduate admission, instruction, and housing for Radcliffe women. In 1999, Radcliffe was formally merged into Harvard University.

21st century

Drew Gilpin Faust, previously the dean of the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, became Harvard University’s first woman president on July 1, 2007. She was succeeded by Lawrence Bacow on July 1, 2018.

The Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics combines the resources and research facilities of the Harvard College Observatory and the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory under a single director to pursue studies of those basic physical processes that determine the nature and evolution of the universe. The Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory is a bureau of the Smithsonian Institution, founded in 1890. The Harvard College Observatory, founded in 1839, is a research institution of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, Harvard University, and provides facilities and substantial other support for teaching activities of the Department of Astronomy.

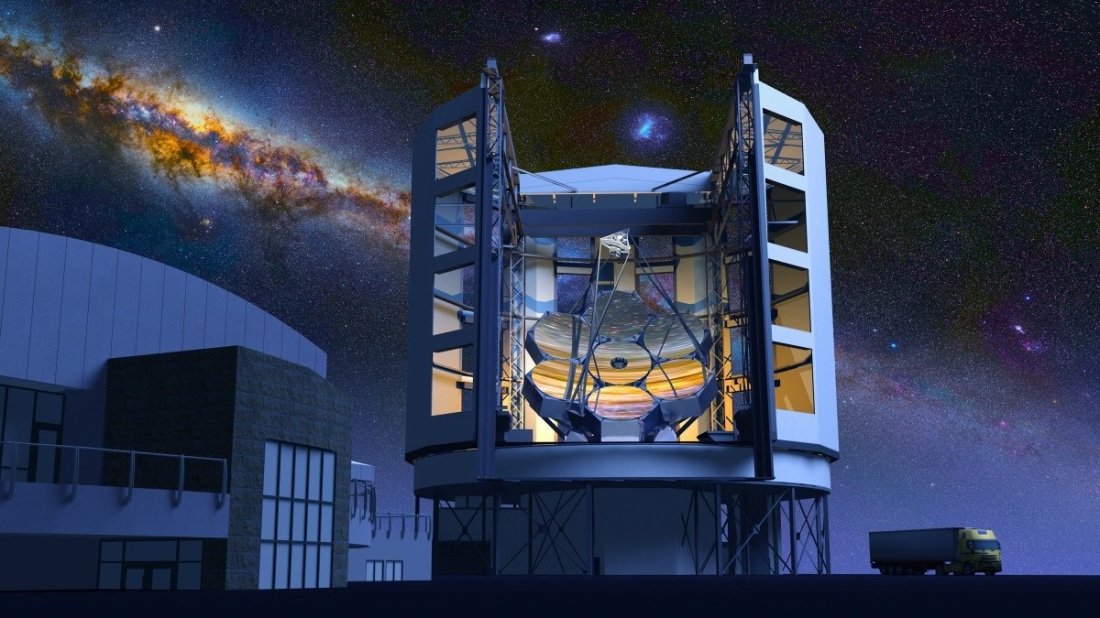

Founded in 1973 and headquartered in Cambridge, Massachusetts, the CfA leads a broad program of research in astronomy, astrophysics, Earth and space sciences, as well as science education. The CfA either leads or participates in the development and operations of more than fifteen ground- and space-based astronomical research observatories across the electromagnetic spectrum, including the forthcoming Giant Magellan Telescope(CL) and the Chandra X-ray Observatory, one of NASA’s Great Observatories.

Giant Magellan Telescope(CL) 21 meters, to be at the Carnegie Institution for Science’s NSF NOIRLab NOAO Las Campanas Observatory(CL) some 115 km (71 mi) north-northeast of La Serena, Chile, over 2,500 m (8,200 ft) high.

Giant Magellan Telescope(CL) 21 meters, to be at the Carnegie Institution for Science’s NSF NOIRLab NOAO Las Campanas Observatory(CL) some 115 km (71 mi) north-northeast of La Serena, Chile, over 2,500 m (8,200 ft) high.

National Aeronautics and Space Administration Chandra X-ray telescope.

National Aeronautics and Space Administration Chandra X-ray telescope.

Hosting more than 850 scientists, engineers, and support staff, the CfA is among the largest astronomical research institutes in the world. Its projects have included Nobel Prize-winning advances in cosmology and high energy astrophysics, the discovery of many exoplanets, and the first image of a black hole. The CfA also serves a major role in the global astrophysics research community: the CfA’s Astrophysics Data System, for example, has been universally adopted as the world’s online database of astronomy and physics papers. Known for most of its history as the “Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics”, the CfA rebranded in 2018 to its current name in an effort to reflect its unique status as a joint collaboration between Harvard University and the Smithsonian Institution. The CfA’s current Director (since 2004) is Charles R. Alcock, who succeeds Irwin I. Shapiro (Director from 1982 to 2004) and George B. Field (Director from 1973 to 1982).

The Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian is not formally an independent legal organization, but rather an institutional entity operated under a Memorandum of Understanding between Harvard University and the Smithsonian Institution. This collaboration was formalized on July 1, 1973, with the goal of coordinating the related research activities of the Harvard College Observatory (HCO) and the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory (SAO) under the leadership of a single Director, and housed within the same complex of buildings on the Harvard campus in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The CfA’s history is therefore also that of the two fully independent organizations that comprise it. With a combined lifetime of more than 300 years, HCO and SAO have been host to major milestones in astronomical history that predate the CfA’s founding.

History of the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory (SAO)

Samuel Pierpont Langley, the third Secretary of the Smithsonian, founded the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory on the south yard of the Smithsonian Castle (on the U.S. National Mall) on March 1,1890. The Astrophysical Observatory’s initial, primary purpose was to “record the amount and character of the Sun’s heat”. Charles Greeley Abbot was named SAO’s first director, and the observatory operated solar telescopes to take daily measurements of the Sun’s intensity in different regions of the optical electromagnetic spectrum. In doing so, the observatory enabled Abbot to make critical refinements to the Solar constant, as well as to serendipitously discover Solar variability. It is likely that SAO’s early history as a solar observatory was part of the inspiration behind the Smithsonian’s “sunburst” logo, designed in 1965 by Crimilda Pontes.

In 1955, the scientific headquarters of SAO moved from Washington, D.C. to Cambridge, Massachusetts to affiliate with the Harvard College Observatory (HCO). Fred Lawrence Whipple, then the chairman of the Harvard Astronomy Department, was named the new director of SAO. The collaborative relationship between SAO and HCO therefore predates the official creation of the CfA by 18 years. SAO’s move to Harvard’s campus also resulted in a rapid expansion of its research program. Following the launch of Sputnik (the world’s first human-made satellite) in 1957, SAO accepted a national challenge to create a worldwide satellite-tracking network, collaborating with the United States Air Force on Project Space Track.

With the creation of National Aeronautics and Space Administration the following year and throughout the space race, SAO led major efforts in the development of orbiting observatories and large ground-based telescopes, laboratory and theoretical astrophysics, as well as the application of computers to astrophysical problems.

History of Harvard College Observatory (HCO)

Partly in response to renewed public interest in astronomy following the 1835 return of Halley’s Comet, the Harvard College Observatory was founded in 1839, when the Harvard Corporation appointed William Cranch Bond as an “Astronomical Observer to the University”. For its first four years of operation, the observatory was situated at the Dana-Palmer House (where Bond also resided) near Harvard Yard, and consisted of little more than three small telescopes and an astronomical clock. In his 1840 book recounting the history of the college, then Harvard President Josiah Quincy III noted that “…there is wanted a reflecting telescope equatorially mounted…”. This telescope, the 15-inch “Great Refractor”, opened seven years later (in 1847) at the top of Observatory Hill in Cambridge (where it still exists today, housed in the oldest of the CfA’s complex of buildings). The telescope was the largest in the United States from 1847 until 1867. William Bond and pioneer photographer John Adams Whipple used the Great Refractor to produce the first clear Daguerrotypes of the Moon (winning them an award at the 1851 Great Exhibition in London). Bond and his son, George Phillips Bond (the second Director of HCO), used it to discover Saturn’s 8th moon, Hyperion (which was also independently discovered by William Lassell).

Under the directorship of Edward Charles Pickering from 1877 to 1919, the observatory became the world’s major producer of stellar spectra and magnitudes, established an observing station in Peru, and applied mass-production methods to the analysis of data. It was during this time that HCO became host to a series of major discoveries in astronomical history, powered by the Observatory’s so-called “Computers” (women hired by Pickering as skilled workers to process astronomical data). These “Computers” included Williamina Fleming; Annie Jump Cannon; Henrietta Swan Leavitt; Florence Cushman; and Antonia Maury, all widely recognized today as major figures in scientific history. Henrietta Swan Leavitt, for example, discovered the so-called period-luminosity relation for Classical Cepheid variable stars, establishing the first major “standard candle” with which to measure the distance to galaxies. Now called “Leavitt’s Law”, the discovery is regarded as one of the most foundational and important in the history of astronomy; astronomers like Edwin Hubble, for example, would later use Leavitt’s Law to establish that the Universe is expanding, the primary piece of evidence for the Big Bang model.

Upon Pickering’s retirement in 1921, the Directorship of HCO fell to Harlow Shapley (a major participant in the so-called “Great Debate” of 1920). This era of the observatory was made famous by the work of Cecelia Payne-Gaposchkin, who became the first woman to earn a Ph.D. in astronomy from Radcliffe College (a short walk from the Observatory). Payne-Gapochkin’s 1925 thesis proposed that stars were composed primarily of hydrogen and helium, an idea thought ridiculous at the time. Between Shapley’s tenure and the formation of the CfA, the observatory was directed by Donald H. Menzel and then Leo Goldberg, both of whom maintained widely recognized programs in solar and stellar astrophysics. Menzel played a major role in encouraging the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory to move to Cambridge and collaborate more closely with HCO.

Joint history as the Center for Astrophysics (CfA)

The collaborative foundation for what would ultimately give rise to the Center for Astrophysics began with SAO’s move to Cambridge in 1955. Fred Whipple, who was already chair of the Harvard Astronomy Department (housed within HCO since 1931), was named SAO’s new director at the start of this new era; an early test of the model for a unified Directorship across HCO and SAO. The following 18 years would see the two independent entities merge ever closer together, operating effectively (but informally) as one large research center.

This joint relationship was formalized as the new Harvard–Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics on July 1, 1973. George B. Field, then affiliated with University of California- Berkeley, was appointed as its first Director. That same year, a new astronomical journal, the CfA Preprint Series was created, and a CfA/SAO instrument flying aboard Skylab discovered coronal holes on the Sun. The founding of the CfA also coincided with the birth of X-ray astronomy as a new, major field that was largely dominated by CfA scientists in its early years. Riccardo Giacconi, regarded as the “father of X-ray astronomy”, founded the High Energy Astrophysics Division within the new CfA by moving most of his research group (then at American Sciences and Engineering) to SAO in 1973. That group would later go on to launch the Einstein Observatory (the first imaging X-ray telescope) in 1976, and ultimately lead the proposals and development of what would become the Chandra X-ray Observatory. Chandra, the second of NASA’s Great Observatories and still the most powerful X-ray telescope in history, continues operations today as part of the CfA’s Chandra X-ray Center. Giacconi would later win the 2002 Nobel Prize in Physics for his foundational work in X-ray astronomy.

Shortly after the launch of the Einstein Observatory, the CfA’s Steven Weinberg won the 1979 Nobel Prize in Physics for his work on electroweak unification. The following decade saw the start of the landmark CfA Redshift Survey (the first attempt to map the large scale structure of the Universe), as well as the release of the Field Report, a highly influential Astronomy & Astrophysics Decadal Survey chaired by the outgoing CfA Director George Field. He would be replaced in 1982 by Irwin Shapiro, who during his tenure as Director (1982 to 2004) oversaw the expansion of the CfA’s observing facilities around the world.

Harvard Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics Fred Lawrence Whipple Observatory located near Amado, Arizona on the slopes of Mount Hopkins, Altitude 2,606 m (8,550 ft).

Harvard Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics Fred Lawrence Whipple Observatory located near Amado, Arizona on the slopes of Mount Hopkins, Altitude 2,606 m (8,550 ft).

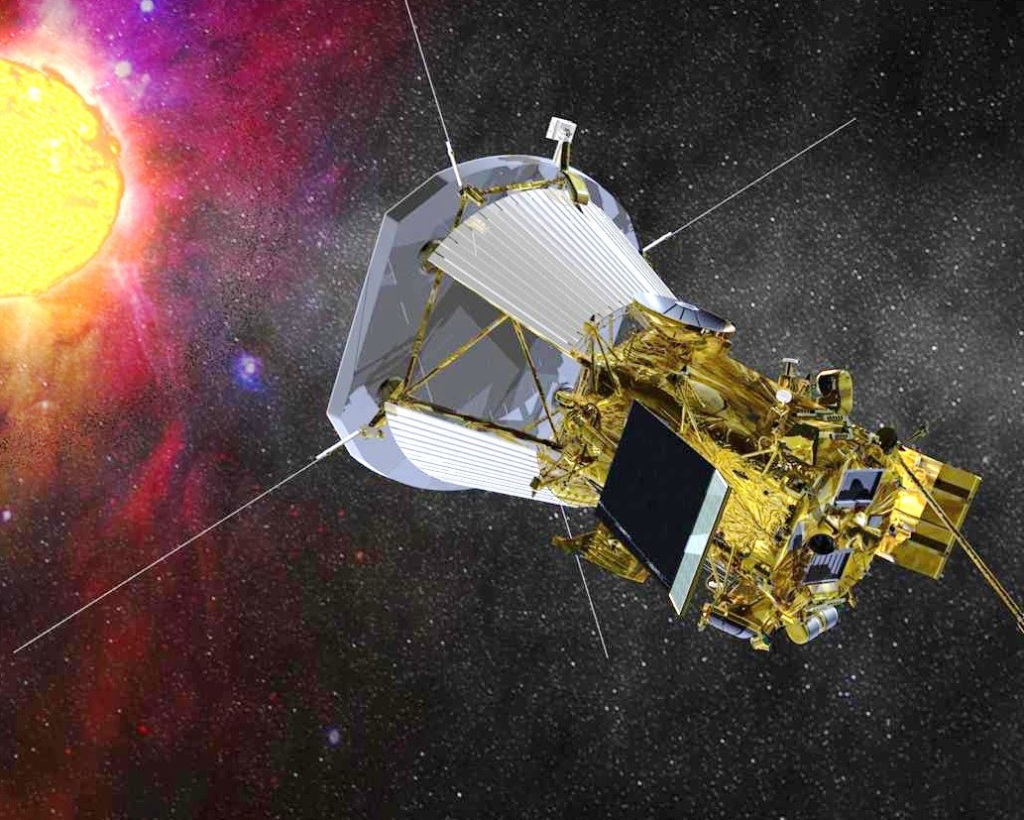

European Space Agency [La Agencia Espacial Europea] [Agence spatiale européenne] [Europäische Weltraumorganization] (EU)/National Aeronautics and Space Administration SOHO satellite. Launched in 1995.

European Space Agency [La Agencia Espacial Europea] [Agence spatiale européenne] [Europäische Weltraumorganization] (EU)/National Aeronautics and Space Administration SOHO satellite. Launched in 1995.

National Aeronautics Space Agency NASA Kepler Space Telescope.

National Aeronautics Space Agency NASA Kepler Space Telescope.

CfA-led discoveries throughout this period include canonical work on Supernova 1987A, the “CfA2 Great Wall” (then the largest known coherent structure in the Universe), the best-yet evidence for supermassive black holes, and the first convincing evidence for an extrasolar planet.

The 1990s also saw the CfA unwittingly play a major role in the history of computer science and the internet: in 1990, SAO developed SAOImage, one of the world’s first X11-based applications made publicly available (its successor, DS9, remains the most widely used astronomical FITS image viewer worldwide). During this time, scientists at the CfA also began work on what would become the Astrophysics Data System (ADS), one of the world’s first online databases of research papers. By 1993, the ADS was running the first routine transatlantic queries between databases, a foundational aspect of the internet today.

The CfA Today

Research at the CfA

Charles Alcock, known for a number of major works related to massive compact halo objects, was named the third director of the CfA in 2004. Today Alcock overseas one of the largest and most productive astronomical institutes in the world, with more than 850 staff and an annual budget in excess of $100M. The Harvard Department of Astronomy, housed within the CfA, maintains a continual complement of approximately 60 Ph.D. students, more than 100 postdoctoral researchers, and roughly 25 undergraduate majors in astronomy and astrophysics from Harvard College. SAO, meanwhile, hosts a long-running and highly rated REU Summer Intern program as well as many visiting graduate students. The CfA estimates that roughly 10% of the professional astrophysics community in the United States spent at least a portion of their career or education there.

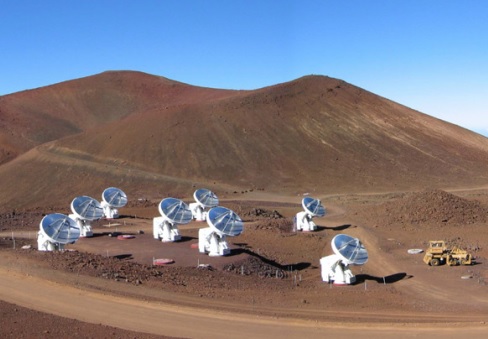

The CfA is either a lead or major partner in the operations of the Fred Lawrence Whipple Observatory, the Submillimeter Array, MMT Observatory, the South Pole Telescope, VERITAS, and a number of other smaller ground-based telescopes. The CfA’s 2019-2024 Strategic Plan includes the construction of the Giant Magellan Telescope as a driving priority for the Center.

CFA Harvard Smithsonian Submillimeter Array on Maunakea, Hawai’i, Altitude 4,205 m (13,796 ft).

CFA Harvard Smithsonian Submillimeter Array on Maunakea, Hawai’i, Altitude 4,205 m (13,796 ft).

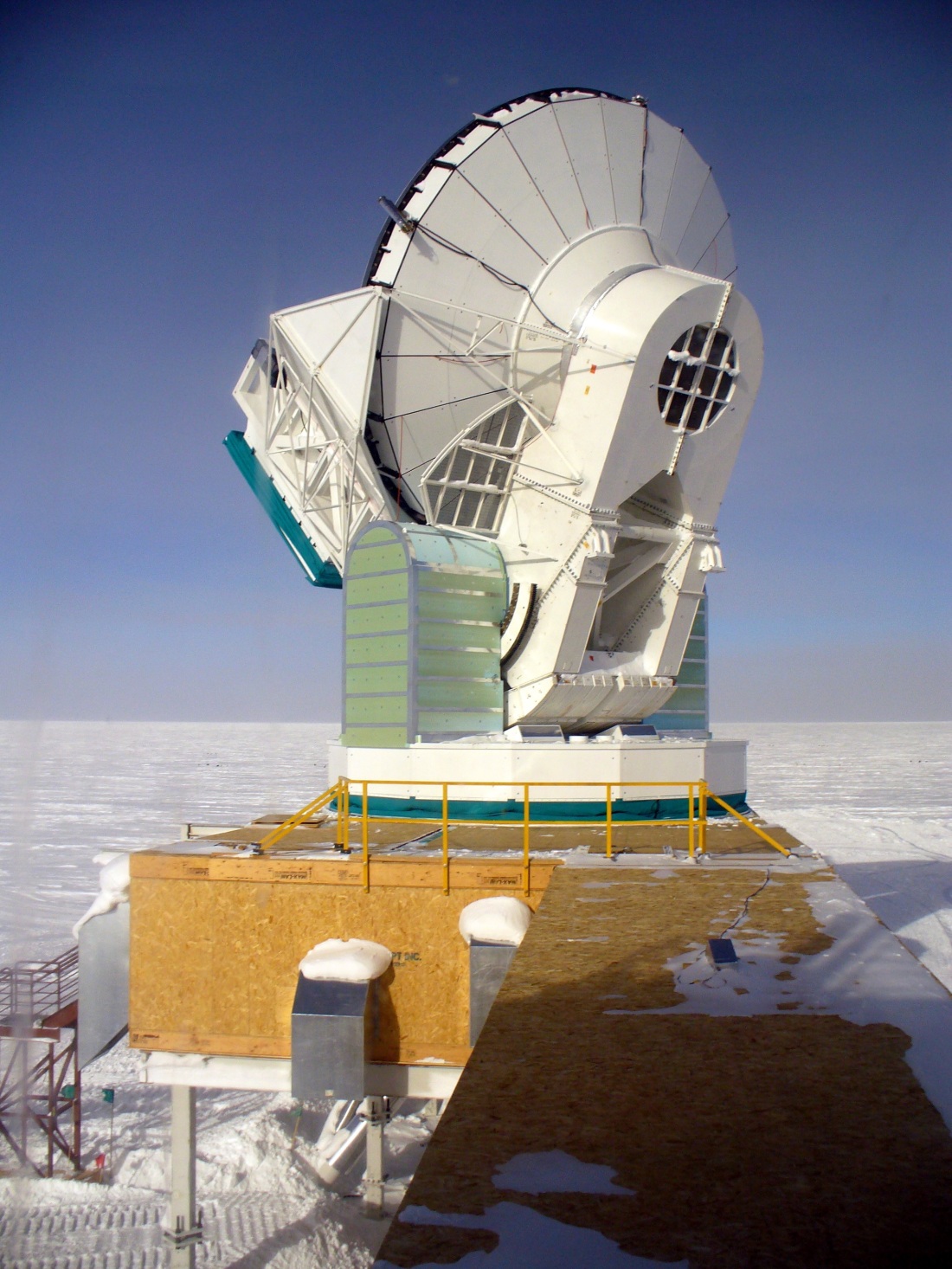

South Pole Telescope SPTPOL. The SPT collaboration is made up of over a dozen (mostly North American) institutions, including The University of Chicago ; The University of California-Berkeley ; Case Western Reserve University; Harvard/Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory; The University of Colorado- Boulder; McGill (CA) University, The University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign; The University of California- Davis; Ludwig Maximilians Universität München(DE); DOE’s Argonne National Laboratory; and The National Institute for Standards and Technology.

South Pole Telescope SPTPOL. The SPT collaboration is made up of over a dozen (mostly North American) institutions, including The University of Chicago ; The University of California-Berkeley ; Case Western Reserve University; Harvard/Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory; The University of Colorado- Boulder; McGill (CA) University, The University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign; The University of California- Davis; Ludwig Maximilians Universität München(DE); DOE’s Argonne National Laboratory; and The National Institute for Standards and Technology.

Along with the Chandra X-ray Observatory, the CfA plays a central role in a number of space-based observing facilities, including the recently launched Parker Solar Probe, Kepler Space Telescope, the Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO), and HINODE. The CfA, via the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory, recently played a major role in the Lynx X-ray Observatory, a NASA-Funded Large Mission Concept Study commissioned as part of the 2020 Decadal Survey on Astronomy and Astrophysics (“Astro2020”). If launched, Lynx would be the most powerful X-ray observatory constructed to date, enabling order-of-magnitude advances in capability over Chandra.

NASA Parker Solar Probe Plus named to honor Pioneering Physicist Eugene Parker. The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Lab.

NASA Parker Solar Probe Plus named to honor Pioneering Physicist Eugene Parker. The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Lab.

National Aeronautics and Space Administration Solar Dynamics Observatory.

National Aeronautics and Space Administration Solar Dynamics Observatory.

Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) (国立研究開発法人宇宙航空研究開発機構] (JP)/National Aeronautics and Space Administration HINODE spacecraft.

Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) (国立研究開発法人宇宙航空研究開発機構] (JP)/National Aeronautics and Space Administration HINODE spacecraft.

SAO is one of the 13 stakeholder institutes for the Event Horizon Telescope Board, and the CfA hosts its Array Operations Center. In 2019, the project revealed the first direct image of a black hole.

Messier 87*, The first image of the event horizon of a black hole. This is the supermassive black hole at the center of the galaxy Messier 87. Image via The Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration released on 10 April 2019 via National Science Foundation.

Messier 87*, The first image of the event horizon of a black hole. This is the supermassive black hole at the center of the galaxy Messier 87. Image via The Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration released on 10 April 2019 via National Science Foundation.

The result is widely regarded as a triumph not only of observational radio astronomy, but of its intersection with theoretical astrophysics. Union of the observational and theoretical subfields of astrophysics has been a major focus of the CfA since its founding.

In 2018, the CfA rebranded, changing its official name to the “Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian” in an effort to reflect its unique status as a joint collaboration between Harvard University and the Smithsonian Institution. Today, the CfA receives roughly 70% of its funding from NASA, 22% from Smithsonian federal funds, and 4% from the National Science Foundation. The remaining 4% comes from contributors including the United States Department of Energy, the Annenberg Foundation, as well as other gifts and endowments.