From The University of California-Riverside

Via

2.10.23

Jules L Bernstein

The magnitude 7.8 earthquake that killed—by current count—more than 20,000 people in Turkey and Syria on Sunday was produced by the same type of fault underlying most of California.

Sunday’s event could be felt more than 200 miles from its epicenter, and it has produced a humanitarian disaster in a region already suffering. As rescuers find more victims in the rubble, the number of dead and injured could increase by as much as eight times the current count, according to the World Health Organization.

Many in earthquake-prone California may have questions about the conditions that caused this tragedy, and whether the western U.S. is likely to suffer a similar fate. UC Riverside seismologist David Oglesby weighs in with answers. Oglesby is a professor of geophysics in UC Riverside’s Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences.

Q: Are the conditions that caused the Turkish earthquake similar to conditions below ground here in California?

A: All earthquakes involve two slabs of rock that slide past each other. The question for us, as seismologists, is, ‘what is the orientation of the slabs, and what direction are they sliding?” There are three fundamental types of faults: normal, reverse, and strike-slip faults.

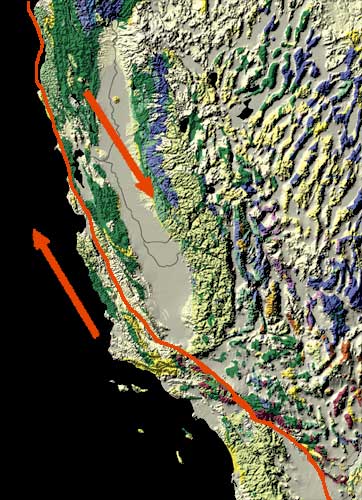

This third type, the strike-slip fault, involves slabs that slide horizontally past each other. The East Anatolian fault in Turkey is a strike-slip fault, much like the the San Andreas fault that crosses much of California from the Salton Sea up to Cape Mendocino.

The San Andreas fault is by no means the only fault in California, but it is the 800-pound gorilla of faults here.

It’s the only one from the Bay area to the Mexican Border that is likely to produce what could approach a magnitude 8 earthquake.

Q: By current counts, more than 5,600 buildings in Turkey were flattened. How is our state likely to fare following a similar event?

A: I am not an engineer, but I believe our structures may fare better than the ones in Sunday’s event did. Most of our buildings, particularly certain critical ones, are designed to withstand significant shaking. Building collapse isn’t as big a danger in California as it is in Turkey. For many people here, a bigger danger is stuff falling. That isn’t to say some buildings won’t collapse.

A 7.8 magnitude event here will still be devastating. Downtown Los Angeles is built on a basin filled with soft sediment that would act like a bowl full of jello in a big earthquake.

In 2008, the U.S. Geological Survey led a study to predict the fallout from an earthquake of this size in Southern California. They estimated more than 1,800 deaths, 50,000 injuries, and $200 billion in damage. People nearest the fault, including those in the Coachella Valley, Inland Empire and Antelope Valley would fare worst.

It’s not a matter of if, but when a quake of roughly this size hits Southern California. People need to take precautions and be prepared.

Q: Studies indicate that earthquakes can send out waves that trigger other earthquakes far from the original epicenter. Is there any possibility of the Turkish earthquake setting off faults on another continent?

A: The Turkish earthquake was easily detected by seismometers here. The question is, did the stress transfer to our faults? Most likely no, it probably did not trigger us. However, there is no magic distance at which triggering ceases. Long-distance stress transfer is an active area of study for us.

In some cases, an earthquake could even relax stress on a nearby fault. Everything depends on the geology and orientation of neighboring faults.

___________________________________________________________________

![]()

Earthquake Network project smartphone ap is a research project which aims at developing and maintaining a crowdsourced smartphone-based earthquake warning system at a global level. Smartphones made available by the population are used to detect the earthquake waves using the on-board accelerometers. When an earthquake is detected, an earthquake warning is issued in order to alert the population not yet reached by the damaging waves of the earthquake.

The project started on January 1, 2013 with the release of the homonymous Android application Earthquake Network. The author of the research project and developer of the smartphone application is Francesco Finazzi of the University of Bergamo, Italy.

Get the app in the Google Play store.

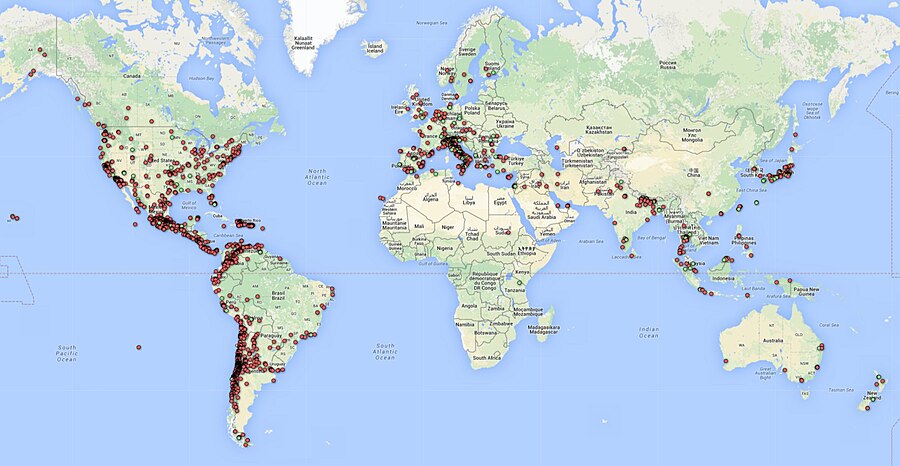

Smartphone network spatial distribution (green and red dots) on December 4, 2015

Meet The Quake-Catcher Network

The Quake-Catcher Network is a collaborative initiative for developing the world’s largest, low-cost strong-motion seismic network by utilizing sensors in and attached to internet-connected computers. With your help, the Quake-Catcher Network can provide better understanding of earthquakes, give early warning to schools, emergency response systems, and others. The Quake-Catcher Network also provides educational software designed to help teach about earthquakes and earthquake hazards.

After almost eight years at Stanford University (US), and a year at California Institute of Technology (US), the QCN project is moving to the University of Southern California (US) Dept. of Earth Sciences. QCN will be sponsored by the Incorporated Research Institutions for Seismology (IRIS) and the Southern California Earthquake Center (SCEC).

The Quake-Catcher Network is a distributed computing network that links volunteer hosted computers into a real-time motion sensing network. QCN is one of many scientific computing projects that runs on the world-renowned distributed computing platform Berkeley Open Infrastructure for Network Computing (BOINC).

The volunteer computers monitor vibrational sensors called MEMS accelerometers, and digitally transmit “triggers” to QCN’s servers whenever strong new motions are observed. QCN’s servers sift through these signals, and determine which ones represent earthquakes, and which ones represent cultural noise (like doors slamming, or trucks driving by).

There are two categories of sensors used by QCN: 1) internal mobile device sensors, and 2) external USB sensors.

Mobile Devices: MEMS sensors are often included in laptops, games, cell phones, and other electronic devices for hardware protection, navigation, and game control. When these devices are still and connected to QCN, QCN software monitors the internal accelerometer for strong new shaking. Unfortunately, these devices are rarely secured to the floor, so they may bounce around when a large earthquake occurs. While this is less than ideal for characterizing the regional ground shaking, many such sensors can still provide useful information about earthquake locations and magnitudes.

USB Sensors: MEMS sensors can be mounted to the floor and connected to a desktop computer via a USB cable. These sensors have several advantages over mobile device sensors. 1) By mounting them to the floor, they measure more reliable shaking than mobile devices. 2) These sensors typically have lower noise and better resolution of 3D motion. 3) Desktops are often left on and do not move. 4) The USB sensor is physically removed from the game, phone, or laptop, so human interaction with the device doesn’t reduce the sensors’ performance. 5) USB sensors can be aligned to North, so we know what direction the horizontal “X” and “Y” axes correspond to.

If you are a science teacher at a K-12 school, please apply for a free USB sensor and accompanying QCN software. QCN has been able to purchase sensors to donate to schools in need. If you are interested in donating to the program or requesting a sensor, click here.

BOINC is a leader in the field(s) of Distributed Computing, Grid Computing and Citizen Cyberscience.BOINC is more properly the Berkeley Open Infrastructure for Network Computing, developed at UC Berkeley.

Earthquake safety is a responsibility shared by billions worldwide. The Quake-Catcher Network (QCN) provides software so that individuals can join together to improve earthquake monitoring, earthquake awareness, and the science of earthquakes. The Quake-Catcher Network (QCN) links existing networked laptops and desktops in hopes to form the worlds largest strong-motion seismic network.

Below, the QCN Quake Catcher Network map

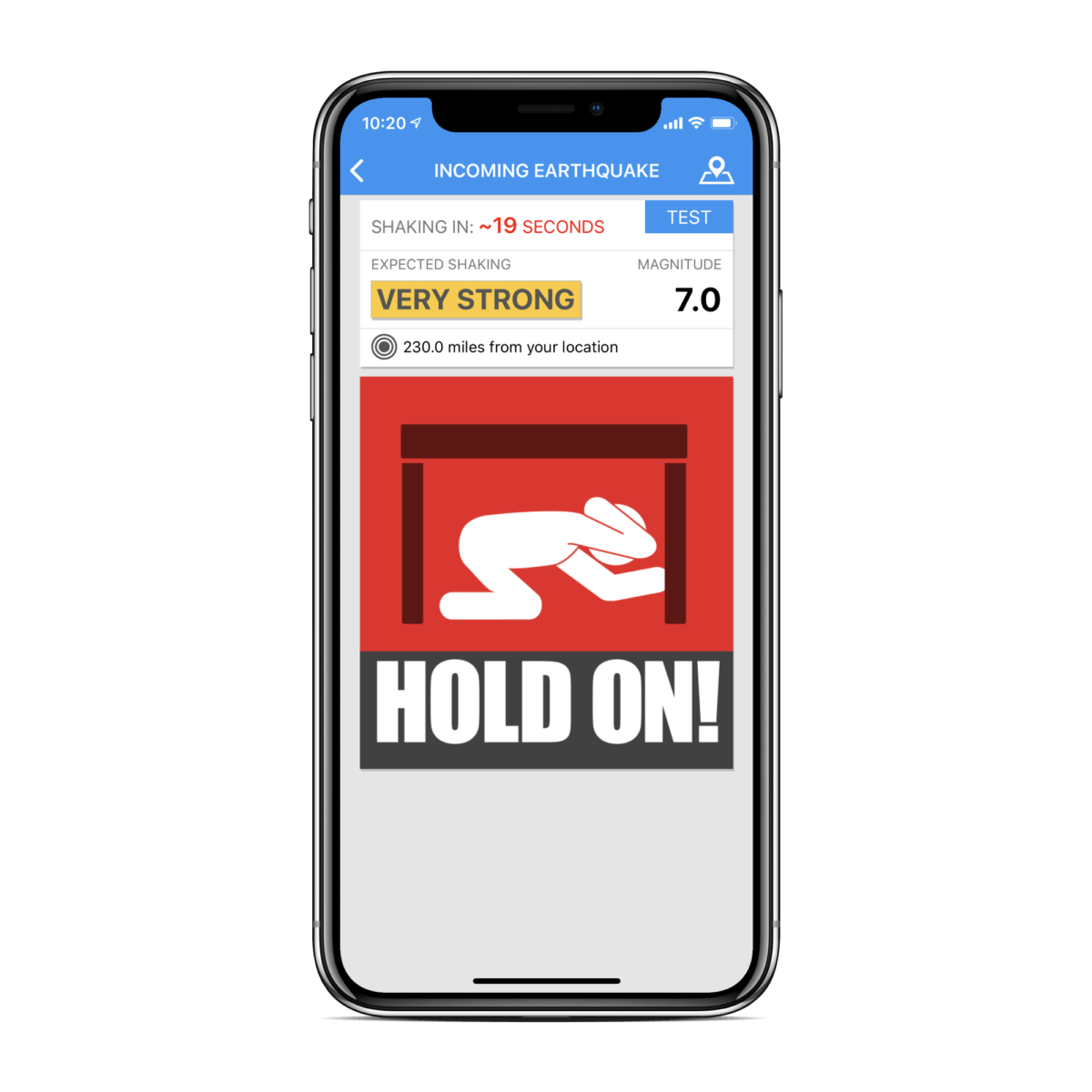

About Early Warning Labs, LLC

Early Warning Labs, LLC (EWL) is an Earthquake Early Warning technology developer and integrator located in Santa Monica, CA. EWL is partnered with industry leading GIS provider ESRI, Inc. and is collaborating with the US Government and university partners.

EWL is investing millions of dollars over the next 36 months to complete the final integration and delivery of Earthquake Early Warning to individual consumers, government entities, and commercial users.

EWL’s mission is to improve, expand, and lower the costs of the existing earthquake early warning systems.

EWL is developing a robust cloud server environment to handle low-cost mass distribution of these warnings. In addition, Early Warning Labs is researching and developing automated response standards

and systems that allow public and private users to take pre-defined automated actions to protect lives and assets.

EWL has an existing beta R&D test system installed at one of the largest studios in Southern California. The goal of this system is to stress test EWL’s hardware, software, and alert signals while improving latency and reliability.

ShakeAlert: An Earthquake Early Warning System for the West Coast of the United States

The U. S. Geological Survey (USGS) along with a coalition of State and university partners is developing and testing an earthquake early warning (EEW) system called ShakeAlert for the west coast of the United States. Long term funding must be secured before the system can begin sending general public notifications, however, some limited pilot projects are active and more are being developed. The USGS has set the goal of beginning limited public notifications in 2018.

Watch a video describing how ShakeAlert works in English or Spanish.

The primary project partners include:

United States Geological Survey

California Governor’s Office of Emergency Services (CalOES)

California Geological Survey California Institute of Technology

University of California Berkeley

University of Washington

University of Oregon

Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation

The Earthquake Threat

Earthquakes pose a national challenge because more than 143 million Americans live in areas of significant seismic risk across 39 states. Most of our Nation’s earthquake risk is concentrated on the West Coast of the United States. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) has estimated the average annualized loss from earthquakes, nationwide, to be $5.3 billion, with 77 percent of that figure ($4.1 billion) coming from California, Washington, and Oregon, and 66 percent ($3.5 billion) from California alone. In the next 30 years, California has a 99.7 percent chance of a magnitude 6.7 or larger earthquake and the Pacific Northwest has a 10 percent chance of a magnitude 8 to 9 megathrust earthquake on the Cascadia subduction zone.

Part of the Solution

Today, the technology exists to detect earthquakes, so quickly, that an alert can reach some areas before strong shaking arrives. The purpose of the ShakeAlert system is to identify and characterize an earthquake a few seconds after it begins, calculate the likely intensity of ground shaking that will result, and deliver warnings to people and infrastructure in harm’s way. This can be done by detecting the first energy to radiate from an earthquake, the P-wave energy, which rarely causes damage. Using P-wave information, we first estimate the location and the magnitude of the earthquake. Then, the anticipated ground shaking across the region to be affected is estimated and a warning is provided to local populations. The method can provide warning before the S-wave arrives, bringing the strong shaking that usually causes most of the damage.

Studies of earthquake early warning methods in California have shown that the warning time would range from a few seconds to a few tens of seconds. ShakeAlert can give enough time to slow trains and taxiing planes, to prevent cars from entering bridges and tunnels, to move away from dangerous machines or chemicals in work environments and to take cover under a desk, or to automatically shut down and isolate industrial systems. Taking such actions before shaking starts can reduce damage and casualties during an earthquake. It can also prevent cascading failures in the aftermath of an event. For example, isolating utilities before shaking starts can reduce the number of fire initiations.

System Goal

The USGS will issue public warnings of potentially damaging earthquakes and provide warning parameter data to government agencies and private users on a region-by-region basis, as soon as the ShakeAlert system, its products, and its parametric data meet minimum quality and reliability standards in those geographic regions. The USGS has set the goal of beginning limited public notifications in 2018. Product availability will expand geographically via ANSS regional seismic networks, such that ShakeAlert products and warnings become available for all regions with dense seismic instrumentation.

Current Status

The West Coast ShakeAlert system is being developed by expanding and upgrading the infrastructure of regional seismic networks that are part of the Advanced National Seismic System (ANSS); the California Integrated Seismic Network (CISN) is made up of the Southern California Seismic Network, SCSN) and the Northern California Seismic System, NCSS and the Pacific Northwest Seismic Network (PNSN). This enables the USGS and ANSS to leverage their substantial investment in sensor networks, data telemetry systems, data processing centers, and software for earthquake monitoring activities residing in these network centers. The ShakeAlert system has been sending live alerts to “beta” users in California since January of 2012 and in the Pacific Northwest since February of 2015.

In February of 2016 the USGS, along with its partners, rolled-out the next-generation ShakeAlert early warning test system in California joined by Oregon and Washington in April 2017. This West Coast-wide “production prototype” has been designed for redundant, reliable operations. The system includes geographically distributed servers, and allows for automatic fail-over if connection is lost.

This next-generation system will not yet support public warnings but does allow selected early adopters to develop and deploy pilot implementations that take protective actions triggered by the ShakeAlert notifications in areas with sufficient sensor coverage.

Authorities

The USGS will develop and operate the ShakeAlert system, and issue public notifications under collaborative authorities with FEMA, as part of the National Earthquake Hazard Reduction Program, as enacted by the Earthquake Hazards Reduction Act of 1977, 42 U.S.C. §§ 7704 SEC. 2.

For More Information

Robert de Groot, ShakeAlert National Coordinator for Communication, Education, and Outreach

rdegroot@usgs.gov

626-583-7225

ShakeAlert Implementation Plan

Earthquake Early Warning Introduction

The United States Geological Survey (USGS), in collaboration with state agencies, university partners, and private industry, is developing an earthquake early warning system (EEW) for the West Coast of the United States called ShakeAlert. The USGS Earthquake Hazards Program aims to mitigate earthquake losses in the United States. Citizens, first responders, and engineers rely on the USGS for accurate and timely information about where earthquakes occur, the ground shaking intensity in different locations, and the likelihood is of future significant ground shaking.

The ShakeAlert Earthquake Early Warning System recently entered its first phase of operations. The USGS working in partnership with the California Governor’s Office of Emergency Services (Cal OES) is now allowing for the testing of public alerting via apps, Wireless Emergency Alerts, and by other means throughout California.

ShakeAlert partners in Oregon and Washington are working with the USGS to test public alerting in those states sometime in 2020.

ShakeAlert has demonstrated the feasibility of earthquake early warning, from event detection to producing USGS issued ShakeAlerts ® and will continue to undergo testing and will improve over time. In particular, robust and reliable alert delivery pathways for automated actions are currently being developed and implemented by private industry partners for use in California, Oregon, and Washington.

Earthquake Early Warning Background

The objective of an earthquake early warning system is to rapidly detect the initiation of an earthquake, estimate the level of ground shaking intensity to be expected, and issue a warning before significant ground shaking starts. A network of seismic sensors detects the first energy to radiate from an earthquake, the P-wave energy, and the location and the magnitude of the earthquake is rapidly determined. Then, the anticipated ground shaking across the region to be affected is estimated. The system can provide warning before the S-wave arrives, which brings the strong shaking that usually causes most of the damage. Warnings will be distributed to local and state public emergency response officials, critical infrastructure, private businesses, and the public. EEW systems have been successfully implemented in Japan, Taiwan, Mexico, and other nations with varying degrees of sophistication and coverage.

Earthquake early warning can provide enough time to:

Instruct students and employees to take a protective action such as Drop, Cover, and Hold On

Initiate mass notification procedures

Open fire-house doors and notify local first responders

Slow and stop trains and taxiing planes

Install measures to prevent/limit additional cars from going on bridges, entering tunnels, and being on freeway overpasses before the shaking starts

Move people away from dangerous machines or chemicals in work environments

Shut down gas lines, water treatment plants, or nuclear reactors

Automatically shut down and isolate industrial systems

However, earthquake warning notifications must be transmitted without requiring human review and response action must be automated, as the total warning times are short depending on geographic distance and varying soil densities from the epicenter.

GNSS-Global Navigational Satellite System

GNSS station | Pacific Northwest Geodetic Array, Central Washington University (US)

___________________________________________________________________

See the full article here .

Comments are invited and will be appreciated, especially if the reader finds any errors which I can correct. Use “Reply”.

five-ways-keep-your-child-safe-school-shootings

Please help promote STEM in your local schools.

University of California-Riverside Campus

University of California-Riverside Campus

The University of California-Riverside is a public land-grant research university in Riverside, California. It is one of the 10 campuses of The University of California system. The main campus sits on 1,900 acres (769 ha) in a suburban district of Riverside with a branch campus of 20 acres (8 ha) in Palm Desert. In 1907, the predecessor to The University of California-Riverside was founded as the UC Citrus Experiment Station, Riverside which pioneered research in biological pest control and the use of growth regulators responsible for extending the citrus growing season in California from four to nine months. Some of the world’s most important research collections on citrus diversity and entomology, as well as science fiction and photography, are located at Riverside.

The University of California-Riverside ‘s undergraduate College of Letters and Science opened in 1954. The Regents of the University of California declared The University of California-Riverside a general campus of the system in 1959, and graduate students were admitted in 1961. To accommodate an enrollment of 21,000 students by 2015, more than $730 million has been invested in new construction projects since 1999. Preliminary accreditation of the The University of California-Riverside School of Medicine was granted in October 2012 and the first class of 50 students was enrolled in August 2013. It is the first new research-based public medical school in 40 years.

The University of California-Riverside is classified among “R1: Doctoral Universities – Very high research activity.” The 2019 U.S. News & World Report Best Colleges rankings places UC-Riverside tied for 35th among top public universities and ranks 85th nationwide. Over 27 of The University of California-Riverside ‘s academic programs, including the Graduate School of Education and the Bourns College of Engineering, are highly ranked nationally based on peer assessment, student selectivity, financial resources, and other factors. Washington Monthly ranked The University of California-Riverside 2nd in the United States in terms of social mobility, research and community service, while U.S. News ranks The University of California-Riverside as the fifth most ethnically diverse and, by the number of undergraduates receiving Pell Grants (42 percent), the 15th most economically diverse student body in the nation. Over 70% of all The University of California-Riverside students graduate within six years without regard to economic disparity. The University of California-Riverside ‘s extensive outreach and retention programs have contributed to its reputation as a “university of choice” for minority students. In 2005, The University of California-Riverside became the first public university campus in the nation to offer a gender-neutral housing option. The University of California-Riverside’s sports teams are known as the Highlanders and play in the Big West Conference of the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) Division I. Their nickname was inspired by the high altitude of the campus, which lies on the foothills of Box Springs Mountain. The University of California-Riverside women’s basketball team won back-to-back Big West championships in 2006 and 2007. In 2007, the men’s baseball team won its first conference championship and advanced to the regionals for the second time since the university moved to Division I in 2001.

History

At the turn of the 20th century, Southern California was a major producer of citrus, the region’s primary agricultural export. The industry developed from the country’s first navel orange trees, planted in Riverside in 1873. Lobbied by the citrus industry, the University of California Regents established the UC Citrus Experiment Station (CES) on February 14, 1907, on 23 acres (9 ha) of land on the east slope of Mount Rubidoux in Riverside. The station conducted experiments in fertilization, irrigation and crop improvement. In 1917, the station was moved to a larger site, 475 acres (192 ha) near Box Springs Mountain.

The 1944 passage of the GI Bill during World War II set in motion a rise in college enrollments that necessitated an expansion of the state university system in California. A local group of citrus growers and civic leaders, including many University of California-Berkeley alumni, lobbied aggressively for a University of California -administered liberal arts college next to the CES. State Senator Nelson S. Dilworth authored Senate Bill 512 (1949) which former Assemblyman Philip L. Boyd and Assemblyman John Babbage (both of Riverside) were instrumental in shepherding through the State Legislature. Governor Earl Warren signed the bill in 1949, allocating $2 million for initial campus construction.

Gordon S. Watkins, dean of the College of Letters and Science at The University of California-Los Angeles, became the first provost of the new college at Riverside. Initially conceived of as a small college devoted to the liberal arts, he ordered the campus built for a maximum of 1,500 students and recruited many young junior faculty to fill teaching positions. He presided at its opening with 65 faculty and 127 students on February 14, 1954, remarking, “Never have so few been taught by so many.”

The University of California-Riverside’s enrollment exceeded 1,000 students by the time Clark Kerr became president of the University of California system in 1958. Anticipating a “tidal wave” in enrollment growth required by the baby boom generation, Kerr developed the California Master Plan for Higher Education and the Regents designated Riverside a general university campus in 1959. The University of California-Riverside’s first chancellor, Herman Theodore Spieth, oversaw the beginnings of the school’s transition to a full university and its expansion to a capacity of 5,000 students. The University of California-Riverside’s second chancellor, Ivan Hinderaker led the campus through the era of the free speech movement and kept student protests peaceful in Riverside. According to a 1998 interview with Hinderaker, the city of Riverside received negative press coverage for smog after the mayor asked Governor Ronald Reagan to declare the South Coast Air Basin a disaster area in 1971; subsequent student enrollment declined by up to 25% through 1979. Hinderaker’s development of innovative programs in business administration and biomedical sciences created incentive for enough students to enroll at University of California-Riverside to keep the campus open.

In the 1990s, The University of California-Riverside experienced a new surge of enrollment applications, now known as “Tidal Wave II”. The Regents targeted The University of California-Riverside for an annual growth rate of 6.3%, the fastest in The University of California system, and anticipated 19,900 students at The University of California-Riverside by 2010. By 1995, African American, American Indian, and Latino student enrollments accounted for 30% of The University of California-Riverside student body, the highest proportion of any University of California campus at the time. The 1997 implementation of Proposition 209—which banned the use of affirmative action by state agencies—reduced the ethnic diversity at the more selective UC campuses but further increased it at The University of California-Riverside.

With The University of California-Riverside scheduled for dramatic population growth, efforts have been made to increase its popular and academic recognition. The students voted for a fee increase to move The University of California-Riverside athletics into NCAA Division I standing in 1998. In the 1990s, proposals were made to establish a law school, a medical school, and a school of public policy at The University of California-Riverside, with The University of California-Riverside School of Medicine and the School of Public Policy becoming reality in 2012. In June 2006, The University of California-Riverside received its largest gift, 15.5 million from two local couples, in trust towards building its medical school. The Regents formally approved The University of California-Riverside’s medical school proposal in 2006. Upon its completion in 2013, it was the first new medical school built in California in 40 years.

Academics

As a campus of The University of California system, The University of California-Riverside is governed by a Board of Regents and administered by a president University of California-Riverside ‘s academic policies are set by its Academic Senate, a legislative body composed of all UC-Riverside faculty members.

The University of California-Riverside is organized into three academic colleges, two professional schools, and two graduate schools. The University of California-Riverside’s liberal arts college, the College of Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences, was founded in 1954, and began accepting graduate students in 1960. The College of Natural and Agricultural Sciences, founded in 1960, incorporated the CES as part of the first research-oriented institution at The University of California-Riverside; it eventually also incorporated the natural science departments formerly associated with the liberal arts college to form its present structure in 1974. The University of California-Riverside ‘s newest academic unit, the Bourns College of Engineering, was founded in 1989. Comprising the professional schools are the Graduate School of Education, founded in 1968, and The University of California-Riverside School of Business, founded in 1970. These units collectively provide 81 majors and 52 minors, 48 master’s degree programs, and 42 Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) programs. The University of California-Riverside is the only UC campus to offer undergraduate degrees in creative writing and public policy and one of three UCs (along with The University of California-Berkeley and The University of California-Irvine) to offer an undergraduate degree in business administration. Through its Division of Biomedical Sciences, founded in 1974, The University of California-Riverside offers the Thomas Haider medical degree program in collaboration with The University of California-Los Angeles. The University of California-Riverside ‘s doctoral program in the emerging field of dance theory, founded in 1992, was the first program of its kind in the United States, and The University of California-Riverside ‘s minor in lesbian, gay and bisexual studies, established in 1996, was the first undergraduate program of its kind in the University of California system. A new BA program in bagpipes was inaugurated in 2007.

Research and economic impact

The University of California-Riverside operated under a $727 million budget in fiscal year 2014–15. The state government provided $214 million, student fees accounted for $224 million and $100 million came from contracts and grants. Private support and other sources accounted for the remaining $189 million. Overall, monies spent at The University of California-Riverside have an economic impact of nearly $1 billion in California. The University of California-Riverside research expenditure in FY 2018 totaled $167.8 million. Total research expenditures at The University of California-Riverside are significantly concentrated in agricultural science, accounting for 53% of total research expenditures spent by the university in 2002. Top research centers by expenditure, as measured in 2002, include the Agricultural Experiment Station; the Center for Environmental Research and Technology; the Center for Bibliographical Studies; the Air Pollution Research Center; and the Institute of Geophysics and Planetary Physics.

Throughout The University of California-Riverside ‘s history, researchers have developed more than 40 new citrus varieties and invented new techniques to help the $960 million-a-year California citrus industry fight pests and diseases. In 1927, entomologists at the CES introduced two wasps from Australia as natural enemies of a major citrus pest, the citrophilus mealybug, saving growers in Orange County $1 million in annual losses. This event was pivotal in establishing biological control as a practical means of reducing pest populations. In 1963, plant physiologist Charles Coggins proved that application of gibberellic acid allows fruit to remain on citrus trees for extended periods. The ultimate result of his work, which continued through the 1980s, was the extension of the citrus-growing season in California from four to nine months. In 1980, The University of California-Riverside released the Oroblanco grapefruit, its first patented citrus variety. Since then, the citrus breeding program has released other varieties such as the Melogold grapefruit, the Gold Nugget mandarin (or tangerine), and others that have yet to be given trademark names.

To assist entrepreneurs in developing new products, The University of California-Riverside is a primary partner in the Riverside Regional Technology Park, which includes the City of Riverside and the County of Riverside. It also administers six reserves of the University of California Natural Reserve System. UC-Riverside recently announced a partnership with China Agricultural University[中国农业大学](CN) to launch a new center in Beijing, which will study ways to respond to the country’s growing environmental issues. University of California-Riverside can also boast the birthplace of two-name reactions in organic chemistry, the Castro-Stephens coupling and the Midland Alpine Borane Reduction.