Feb 27, 2020

Jack Wang

A car mirror isn’t the only thing that can warp images. Our brains do that on their own, and a new study complicates the scientific understanding of when—or why—that happens. Copyright Shutterstock.com.

Study challenges long-held understanding of concept known as boundary extension.

When people remember images, they fill in the edges with details they didn’t actually see. That’s the idea behind the boundary extension, a term which has become widely accepted in psychology classes, textbooks and test-prep flashcards.

But what if the concept isn’t quite accurate?

A University of Chicago psychologist has discovered new evidence that challenges the decades-old understanding of the memory error as a universal phenomenon. Published in the journal Current Biology, the study proposes that boundary contraction may be just as common as boundary extension—and that whether something appears zoomed in or out depends on the properties of the image itself.

“In a way, we’re debunking this very strong claim that has been made in psychology over the last 30 years,” said Asst. Prof. Wilma Bainbridge, the study’s lead author and an expert on the perception and memorability of images.

The finding is important, she added, because boundary extension has been used to make other claims about the nature of the brain, such as the function of the hippocampus.

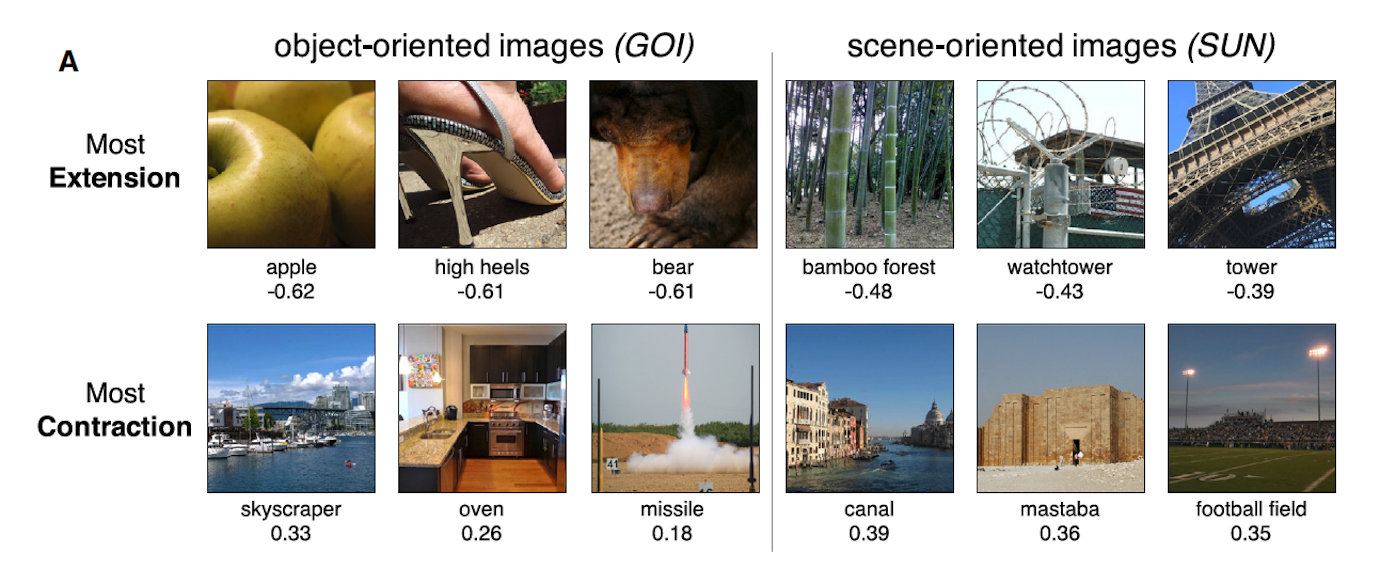

Bainbridge co-authored the study with Chris Baker, a principal investigator at the National Institute of Mental Health. Testing 2,000 participants, they found that although images of objects caused boundary extension, images of full scenes were more likely to produce boundary contraction. That is, a person may see a close-up photo of an apple and fill in details that were not actually present. But if they see a football field, they may be more likely to remove details—zooming in, or contracting, the actual image.

The study relied on two databases, Google Open Images (SOI) and the Scene Understanding Database (SUN), which categorized images using object- and scene-oriented words. Courtesy of Wilma Bainbridge.

In a previous study [Nature Communications], Bainbridge and Baker showed participants various images and asked them to draw copies. They were “perplexed” when boundary extension did not occur as often as they had expected.

To further investigate those results, they conducted an online experiment using a broad set of 1,000 images and 2,000 participants. Participants would see an image, see a scrambled image and then see the original image again.

Even though the final image was identical to the first, the researchers found that people would indicate it being farther or closer according to its visual properties (object-based vs. scene-based).

Bainbridge said the results highlight the need for psychologists to revisit even long-held assumptions, as well as the potential pitfalls of drawing larger inferences from limited data sets.

Past replications of boundary extension, she suggested, could have been skewed in part by narrow data sets that repeated the use of certain image types.

“Anecdotally, I’ve spoken with many people who have thought about looking at boundary extension—but then they aren’t able to replicate the effects, so they give up and they set aside the data,” she said.

See the full article here .

five-ways-keep-your-child-safe-school-shootings

Please help promote STEM in your local schools.

An intellectual destination

One of the world’s premier academic and research institutions, the University of Chicago has driven new ways of thinking since our 1890 founding. Today, UChicago is an intellectual destination that draws inspired scholars to our Hyde Park and international campuses, keeping UChicago at the nexus of ideas that challenge and change the world.

The University of Chicago is an urban research university that has driven new ways of thinking since 1890. Our commitment to free and open inquiry draws inspired scholars to our global campuses, where ideas are born that challenge and change the world.

We empower individuals to challenge conventional thinking in pursuit of original ideas. Students in the College develop critical, analytic, and writing skills in our rigorous, interdisciplinary core curriculum. Through graduate programs, students test their ideas with UChicago scholars, and become the next generation of leaders in academia, industry, nonprofits, and government.

UChicago research has led to such breakthroughs as discovering the link between cancer and genetics, establishing revolutionary theories of economics, and developing tools to produce reliably excellent urban schooling. We generate new insights for the benefit of present and future generations with our national and affiliated laboratories: Argonne National Laboratory, Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, and the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, Massachusetts.

The University of Chicago is enriched by the city we call home. In partnership with our neighbors, we invest in Chicago’s mid-South Side across such areas as health, education, economic growth, and the arts. Together with our medical center, we are the largest private employer on the South Side.

In all we do, we are driven to dig deeper, push further, and ask bigger questions—and to leverage our knowledge to enrich all human life. Our diverse and creative students and alumni drive innovation, lead international conversations, and make masterpieces. Alumni and faculty, lecturers and postdocs go on to become Nobel laureates, CEOs, university presidents, attorneys general, literary giants, and astronauts.