From The Arizona State University

4.25.24

Jay Thorne

jay.thorne@asu.edu

Illustration by Alex Cabrera/ASU

“Gradually, and then suddenly.”

It’s not only a famous line from Ernest Hemingway’s novel “The Sun Also Rises,” it’s an apt description of how Arizona has transitioned from an economy based on its historical “5 C’s” to one centered on a sustainable high-tech industry.

A transformation fueled by Arizona State University.

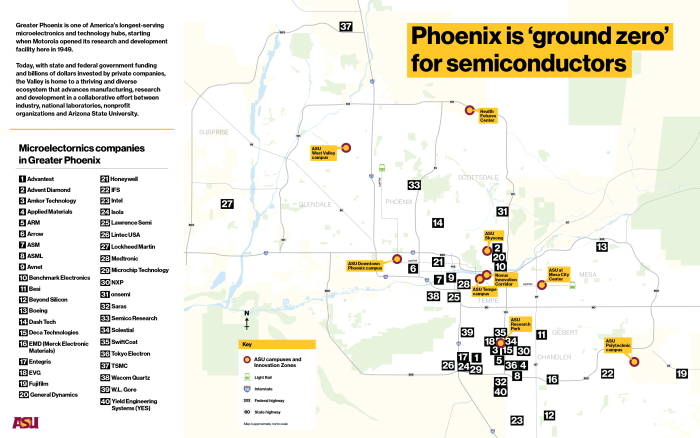

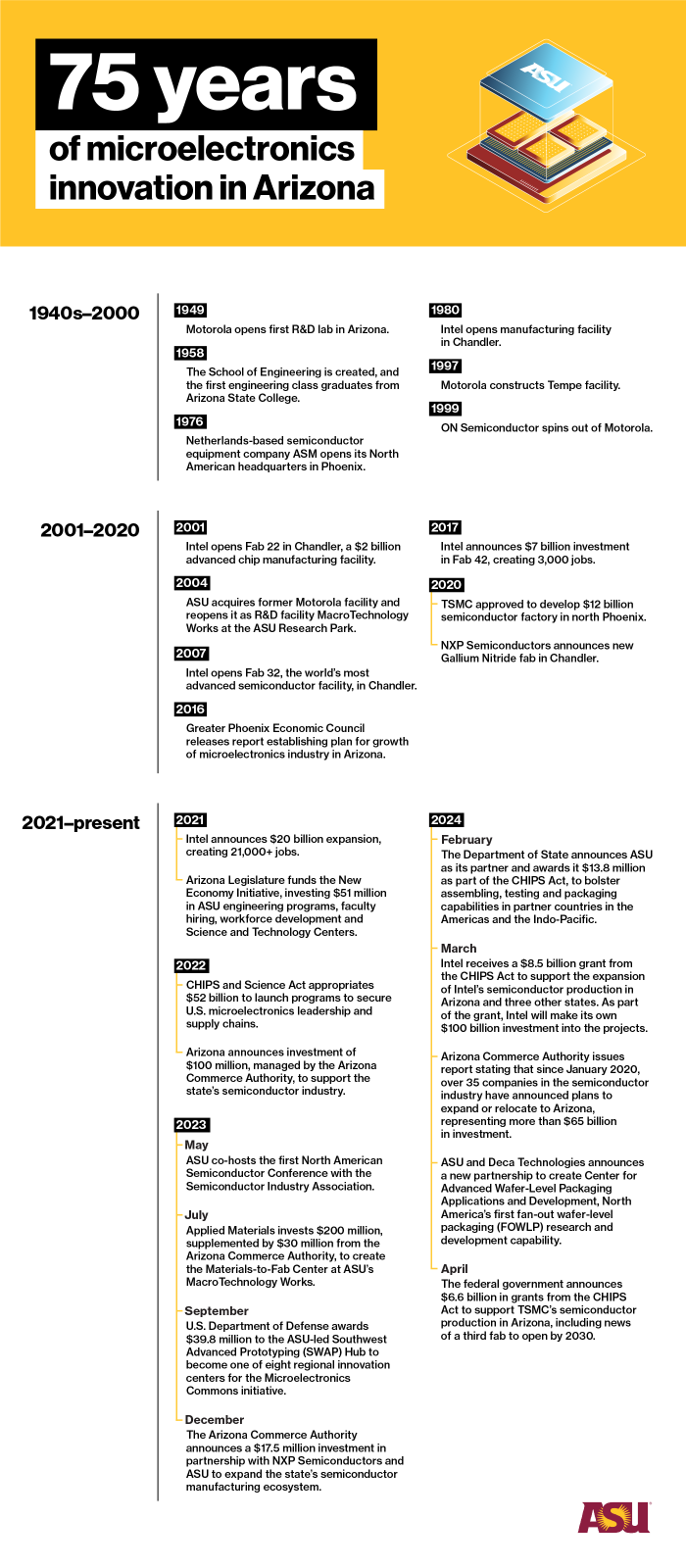

In 1949, when Motorola opened its first research and development center in Phoenix, ASU did not yet exist; it was Arizona State College. By 1958, a university was born — and with it, the School of Engineering. In those same years, the transistor era emerged and the American semiconductor industry took off, including roots here in the Valley.

The industry grew through the 1960s and ’70s with Arizona companies making a contribution, but by the mid-1980s, Japan had overtaken the U.S. as the world’s top semiconductor producer. Although the U.S. regained market share in the 1990s, the industry had gone global.

Research and innovation continued to be strengths of the American market, but competition and economic incentives had driven manufacturing overseas. ASU’s School of Engineering enjoyed steady growth in these years, increasing enrollment and broadening its scope to meet demand and match opportunity.

As the industry developed, occasional chip shortages were part of the landscape. But as the dependence grew on microchips for consumer goods, the impact of supply chain disruptions grew with it.

Then the COVID-19 pandemic — combined with geopolitical factors — changed everything.

Suddenly there were critical shortages leading to lengthy backlogs for electronics used in smartphones, computers, cars and even home appliances. The wider public was aware, perhaps for the first time, just how precarious the semiconductor chips supply was.

The microchip gap became a national priority, not only for commercial purposes but as a matter of national security.

The CHIPS and Science Act was born, authorized during the Trump administration in 2020 and funded during the Biden administration through bipartisan congressional action in 2022.

ASU was prepared to be a player.

“The world that we’re building is not the world we are coming out of. Microchips are now going to be the rough equivalency of electricity — or water,” ASU President Michael Crow said. “Arizona State University is a national service university, built to accelerate positive outcomes through the integration of cutting-edge technological innovation and to be responsive in moments like this that call upon us to work collaboratively to pursue goals in the vital interest of our country.”

The university’s preparation came through many endeavors:

-Growing the Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering.

-Helping to inform state and federal public policy to create strategy that will re-establish the domestic semiconductor industry, resulting in Arizona’s New Economy initiative and America’s CHIPS and Science Act.

-Developing Science and Technology Centers for collaboration with the private sector.

-Re-inventing a Motorola R&D facility as the MacroTechnology Works facility at ASU Research Park, a home for collaboration between the private sector and academia, and a way to bridge the so-called “Valley of Death” — the phase between research and implementation or commercialization where technology often fails to launch to market.

-Expanding and deepening partnerships with semiconductor industry companies investing in Arizona.

-Working with local leadership to attract new industry investment and locations in Arizona, which resulted in TSMC choosing Phoenix as the location for its first American manufacturing plant.

-Opening a School of Manufacturing Systems and Networks as part of the Fulton Schools of Engineering, for greater focus on producing the workforce needed for domestic semiconductor manufacturing.

-Leading one of eight Department of Defense Microelectronics Commons innovation hubs — the Southwest Advanced Prototyping Hub — to develop microelectronics critical for the next generation of defense systems that will keep America safe.

-Partnering with the U.S. Department of State on a new initiative to bolster semiconductor manufacturing in the Americas and Indo-Pacific, a “near-shoring” strategy under the CHIPS Act to create a more resilient supply chain for U.S. semiconductor manufacturers.

Bolstering the state’s economy

Industry and community leaders agree that the contributions from ASU have been central to the success the state of Arizona has achieved in building its semiconductor industry. Arizona now leads the nation in recent private-sector semiconductor investments with $64 billion since 2021.

Economic impact and public policy consultant Jim Rounds, who has argued for greater investment in higher education to drive economic opportunity in Arizona, characterizes the impact as the equivalent of landing the Super Bowl — 10 times, every year.

“We’re a hot spot for semiconductor manufacturing,” Rounds said. “If we continue to expand, even if we just maintain the current pace … the numbers are staggering. When somebody says a billion dollars, it’s hard to relate to. But just for context, for every thousand workers in semiconductor manufacturing, that generates tax revenue equivalent to a Super Bowl. And we’re not talking about a thousand, we’re talking about tens of thousands.”

Sandra Watson, president and CEO of the Arizona Commerce Authority, said Arizona’s efforts to revitalize the microelectronics industry began after the Great Recession of 2008, with state leadership aggressively promoting Arizona to relevant industry leaders around the world. That outreach included a trip she and other local economic development representatives took to Taiwan in 2013, which initiated discussions with TSMC about why Arizona deserved serious consideration if the company were ever to establish its first factory outside of Taiwan.

“Arizona is establishing itself as the epicenter of America’s semiconductor industry, and our universities are key to making that happen,” Watson said. “So, we are very fortunate to have Arizona State University to help advance microelectronics in our state, and we continue to seek opportunities to work together in accelerating the pace of industry growth. I just can’t say enough about this partnership, and President Crow’s leadership has been incredible.”

The packaging play: The future of semiconductor innovation : Arizona State University (ASU)

Video by Media Relations Visual Communications

Contributing to the workforce

The effort to attract TSMC was a fierce competition that involved many leaders in Arizona, including ASU. Phoenix Mayor Kate Gallego was one of those who went to Taiwan in fall 2019 to support the Greater Phoenix Economic Council in a pitch to TSMC.

“I have a background in power and water, so I was able to talk about the business attributes of our community in those areas,” Gallego said. “But they really wanted to talk about Arizona State University. They wanted to know they would have a well-educated workforce. It turned out our secret weapon in capturing their attention was ASU.”

ASU’s eight schools in the Fulton Schools of Engineering collectively represent the largest college of engineering in America, with more than 32,000 students — and more than 7,000 of them are pursuing education in fields directly related to microelectronics. This major pipeline of talent is important to many businesses already well established in Arizona.

“We’ve been growing and expanding, and we’ve been positioning through that growth and expansion to meet workforce needs as companies grow their footprint,” said Kyle Squires, Fulton Schools dean. “And we’ve been advancing not just the workforce training that we provide to new graduates, but also connection to supporting industry through faculty engagement, through research and also working together with the state to position the state for CHIPS Act opportunities.”

And because the industry needs not only new college graduates but also retraining for existing workers and those who do not hold four-year degrees, ASU has responded with options.

“When we think about the workforce, we’re thinking about the regular college student, everywhere from a bachelor’s to master’s to a PhD, but we’re also doing a lot of work in the pieces around that — like certificates, short courses and upskilling — so that people who want to change careers can do so and do so easily,” said Sally Morton, executive vice president of ASU’s Knowledge Enterprise.

“This will take a skilled workforce and a large one, so we very much want to be part of meeting that demand,” she said, noting that the nearly $53 billion investment from the CHIPS Act surpasses that of the Manhattan Project, in inflation-adjusted terms.

Illustration by Alex Cabrera/ASU

Serving up the lab and fabrication space

One of ASU’s most distinctive assets is the MacroTechnology Works, or MTW, facility.

MTW has been central to much of the recent activity making Arizona a focus of America’s microelectronics revival. It has captured attention worldwide and welcomed such visitors as U.S. Department of Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo, leaders from the U.S. Department of Defense and European Union leadership.

MTW is a place where private industry — of all sizes — and academia come together, turning ideas into commercially viable products. The facility provides companies access not just to brainpower, but to key equipment.

“Companies don’t have to purchase, install and maintain capital equipment that they might need in order to do prototyping, because a university does that,” said Zachary Holman, vice dean for research and innovation for the Fulton Schools. “They don’t have to hire and train staff members who embody the knowledge to run that equipment, because the university does that too. We lower the bar in terms of time and money. And help them reach their goals.

As a result of its unique value proposition, MTW has attracted considerable outside investment.

Last July, Applied Materials made a more than $200 million investment with support from the Arizona Commerce Authority in tooling equipment to establish a Materials-to-Fab Center to advance new semiconductor materials deposition technology.

In December, NXP Semiconductors began a new partnership with ASU, supported by significant investment from the Arizona Commerce Authority, to expand new advanced packaging and workforce training capabilities.

And as recently as March of this year, Deca Technologies and ASU announced a partnership to create North America’s first Fan-Out Wafer-Level Packaging research and development capability. The new Center for Advanced Wafter-Level Packaging Applications and Development will be located inside the MTW.

The industry partnerships that have driven these investments are closely connected both to the research and the opportunity to develop the skilled workforce that every company desperately needs as this competitive industry moves forward.

Grace O’Sullivan, ASU’s vice president of corporate engagement and strategic partnerships, was one of the people who traveled to Taiwan as part of the pitch to TSMC to attract the company here. She has attended two visits from the U.S. president to distribute CHIPS Act funding to companies in Arizona. She knows that while Intel and TSMC were the recipients of that investment, it represents a win for the entire state — and it was a team effort to make it happen.

“It’s an interdisciplinary effort to make all of this work between government agencies, universities and community colleges, and these things don’t happen overnight,” O’Sullivan said. “Greater Phoenix Economic Council, Arizona Commerce Authority and ASU, under the vision of ASU President Michael Crow, have been planning this for years.”

Gradual work that has suddenly paid off for the state of Arizona.

See the full article here.

Comments are invited and will be appreciated, especially if the reader finds any errors which I can correct.

five-ways-keep-your-child-safe-school-shootings

Please help promote STEM in your local schools.

The Arizona State University Tempe Campus.

The Arizona State University is a public research university in the Phoenix metropolitan area. Founded in 1885 by the 13th Arizona Territorial Legislature, ASU is one of the largest public universities by enrollment in the U.S.

One of three universities governed by the Arizona Board of Regents, The Arizona State University is a member of the Association of American Universities and classified among “R1: Doctoral Universities – Very High Research Activity.” The Arizona State University has more than 150,000 students attending classes, with more than 38,000 students attending online, and over 90,000 undergraduates and more nearly 20,000 postgraduates across its five campuses and four regional learning centers throughout Arizona. The Arizona State University offers 350 degree options from its 17 colleges and more than 170 cross-discipline centers and institutes for undergraduates students, as well as more than 400 graduate degree and certificate programs. The Arizona State Sun Devils compete in 26 varsity-level sports in the NCAA Division I Pac-12 Conference and is home to over 1,100 registered student organizations.

The Arizona State University ‘s charter, approved by the board of regents in 2014, is based on the New American University model created by The Arizona State University President Michael M. Crow upon his appointment as the institution’s 16th president in 2002. It defines The Arizona State University as “a comprehensive public research university, measured not by whom it excludes, but rather by whom it includes and how they succeed; advancing research and discovery of public value; and assuming fundamental responsibility for the economic, social, cultural and overall health of the communities it serves.” The model is widely credited with boosting The Arizona State University ‘s acceptance rate and increasing class size.

The university’s faculty of more than 4,700 scholars has included Nobel laureates, Pulitzer Prize winners, MacArthur Fellows, and National Academy of Sciences members. Additionally, among the faculty are Fulbright Program American Scholars, National Endowment for the Humanities fellows, American Council of Learned Societies fellows, members of the Guggenheim Fellowship, members of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, members of National Academy of Inventors, National Academy of Engineering members and National Academy of Medicine members. The National Academies has bestowed “highly prestigious” recognition on a large number of Arizona State University faculty members.

History

The Arizona State University was established as the Territorial Normal School at Tempe on March 12, 1885, when the 13th Arizona Territorial Legislature passed an act to create a normal school to train teachers for the Arizona Territory. The campus consisted of a single, four-room schoolhouse on a 20-acre plot largely donated by Tempe residents George and Martha Wilson. Classes began with 33 students on February 8, 1886. The curriculum evolved over the years and the name was changed several times; the institution was also known as Tempe Normal School of Arizona (1889–1903), Tempe Normal School (1903–1925), Tempe State Teachers College (1925–1929), Arizona State Teachers College (1929–1945), Arizona State College (1945–1958) and, by a 2–1 margin of the state’s voters, The Arizona State University in 1958.

In 1923, the school stopped offering high school courses and added a high school diploma to the admissions requirements. In 1925, the school became the Tempe State Teachers College and offered four-year Bachelor of Education degrees as well as two-year teaching certificates. In 1929, the 9th Arizona State Legislature authorized Bachelor of Arts in Education degrees as well, and the school was renamed The Arizona State Teachers College. Under the 30-year tenure of president Arthur John Matthews (1900–1930), the school was given all-college student status. The first dormitories built in the state were constructed under his supervision in 1902. Of the 18 buildings constructed while Matthews was president, six are still in use. Matthews envisioned an “evergreen campus,” with many shrubs brought to the campus, and implemented the planting of 110 Mexican Fan Palms on what is now known as Palm Walk, a century-old landmark of the Tempe campus.

During the Great Depression, Ralph Waldo Swetman was hired to succeed President Matthews, coming to The Arizona State Teachers College in 1930 from The Humboldt State Teachers College where he had served as president. He served a three-year term, during which he focused on improving teacher-training programs. During his tenure, enrollment at the college doubled, topping the 1,000 mark for the first time. Matthews also conceived of a self-supported summer session at the school at The Arizona State Teachers College, a first for the school.

1930–1989

In 1933, Grady Gammage, then president of The Arizona State Teachers College at Flagstaff, became president of The Arizona State Teachers College at Tempe, beginning a tenure that would last for nearly 28 years, second only to Swetman’s 30 years at the college’s helm. Like President Arthur John Matthews before him, Gammage oversaw the construction of several buildings on the Tempe campus. He also guided the development of the university’s graduate programs; the first Master of Arts in Education was awarded in 1938, the first Doctor of Education degree in 1954 and 10 non-teaching master’s degrees were approved by the Arizona Board of Regents in 1956. During his presidency, the school’s name was changed to Arizona State College in 1945, and finally to The Arizona State University in 1958. At the time, two other names were considered: Tempe University and State University at Tempe. Among Gammage’s greatest achievements in Tempe was the Frank Lloyd Wright-designed construction of what is Grady Gammage Memorial Auditorium/ASU Gammage. One of the university’s hallmark buildings, Arizona State University Gammage was completed in 1964, five years after the president’s (and Wright’s) death.

Gammage was succeeded by Harold D. Richardson, who had served the school earlier in a variety of roles beginning in 1939, including director of graduate studies, college registrar, dean of instruction, dean of the College of Education and academic vice president. Although filling the role of acting president of the university for just nine months (Dec. 1959 to Sept. 1960), Richardson laid the groundwork for the future recruitment and appointment of well-credentialed research science faculty.

By the 1960s, under G. Homer Durham, the university’s 11th president, The Arizona State University began to expand its curriculum by establishing several new colleges and, in 1961, the Arizona Board of Regents authorized doctoral degree programs in six fields, including Doctor of Philosophy. By the end of his nine-year tenure, The Arizona State University had more than doubled enrollment, reporting 23,000 in 1969.

The next three presidents—Harry K. Newburn (1969–71), John W. Schwada (1971–81) and J. Russell Nelson (1981–89), including and Interim President Richard Peck (1989), led the university to increased academic stature, the establishment of The Arizona State University West campus in 1984 and its subsequent construction in 1986, a focus on computer-assisted learning and research, and rising enrollment.

1990–present

Under the leadership of Lattie F. Coor, president from 1990 to 2002, The Arizona State University grew through the creation of the Polytechnic campus and extended education sites. Increased commitment to diversity, quality in undergraduate education, research, and economic development occurred over his 12-year tenure. Part of Coor’s legacy to the university was a successful fundraising campaign: through private donations, more than $500 million was invested in areas that would significantly impact the future of The Arizona State University. Among the campaign’s achievements were the naming and endowing of Barrett, The Honors College, and the Herberger Institute for Design and the Arts; the creation of many new endowed faculty positions; and hundreds of new scholarships and fellowships.

In 2002, Michael M. Crow became the university’s 16th president. At his inauguration, he outlined his vision for transforming The Arizona State University into a “New American University”—one that would be open and inclusive, and set a goal for the university to meet Association of American Universities criteria and to become a member. Crow initiated the idea of transforming The Arizona State University into “One university in many places”—a single institution comprising several campuses, sharing students, faculty, staff and accreditation. Subsequent reorganizations combined academic departments, consolidated colleges and schools, and reduced staff and administration as the university expanded its West and Polytechnic campuses. The Arizona State University’s Downtown Phoenix campus was also expanded, with several colleges and schools relocating there. The university established learning centers throughout the state, including The Arizona State University Colleges at Lake Havasu City and programs in Thatcher, Yuma, and Tucson. Students at these centers can choose from several Arizona State University degree and certificate programs.

During Crow’s tenure, and aided by hundreds of millions of dollars in donations, The Arizona State University began a years-long research facility capital building effort that led to the establishment of the Biodesign Institute at The Arizona State University, the Julie Ann Wrigley Global Institute of Sustainability, and several large interdisciplinary research buildings. Along with the research facilities, the university faculty was expanded, including the addition of Nobel Laureates. Since 2002, the university’s research expenditures have tripled and more than 1.5 million square feet of space has been added to the university’s research facilities.

The economic downturn that began in 2008 took a particularly hard toll on Arizona, resulting in large cuts to The Arizona State University ‘s budget. In response to these cuts, The Arizona State University capped enrollment, closed some four dozen academic programs, combined academic departments, consolidated colleges and schools, and reduced university faculty, staff and administrators; however, with an economic recovery underway in 2011, the university continued its campaign to expand the West and Polytechnic Campuses, and establish a low-cost, teaching-focused extension campus in Lake Havasu City.

The Arizona State University’s research funding has almost tripled. Degree production has increased by 45 percent. And thanks to an ambitious aid program, enrollment of students from Arizona families below poverty is up 647 percent.”

In 2015, the Thunderbird School of Global Management became the fifth Arizona State University campus, as the Thunderbird School of Global Management at The Arizona State University. Partnerships for education and research with Mayo Clinic established collaborative degree programs in health care and law, and shared administrator positions, laboratories and classes at the Mayo Clinic Arizona campus.

The Beus Center for Law and Society, the new home of The Arizona State University’s Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law, opened in fall 2016 on the Downtown Phoenix campus, relocating faculty and students from the Tempe campus to the state capital.