From The University of Cambridge (UK)

4.24.24

Sarah Collins

sarah.collins@admin.cam.ac.uk

Getty Images

Researchers have found a way to super-charge the ‘engine’ of sustainable fuel generation – by giving the materials a little twist.

The researchers, led by the University of Cambridge, are developing low-cost light-harvesting semiconductors that power devices for converting water into clean hydrogen fuel, using just the power of the sun. These semiconducting materials, known as copper oxides, are cheap, abundant and non-toxic, but their performance does not come close to silicon, which dominates the semiconductor market.

However, the researchers found that by growing the copper oxide crystals in a specific orientation so that electric charges move through the crystals at a diagonal, the charges move much faster and further, greatly improving performance. Tests of a copper oxide light harvester, or photocathode, based on this fabrication technique showed a 70% improvement over existing state-of-the-art oxide photocathodes, while also showing greatly improved stability.

The researchers say their results, reported in the journal Nature, show how low-cost materials could be fine-tuned to power the transition away from fossil fuels and toward clean, sustainable fuels that can be stored and used with existing energy infrastructure.

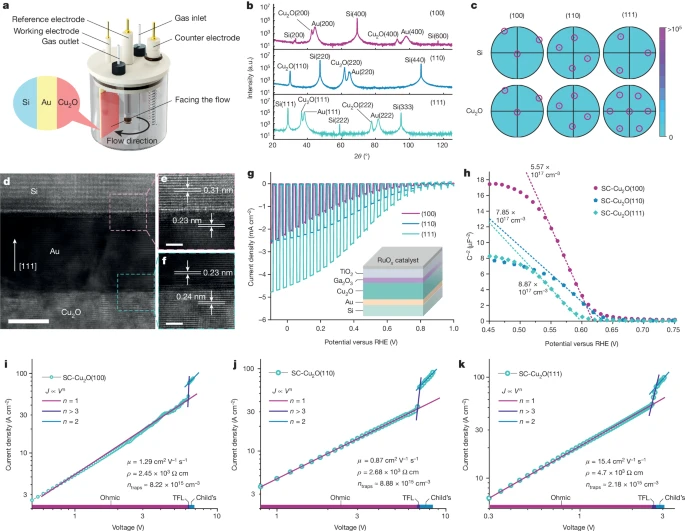

Fig. 1: SC-Cu2O thin films show anisotropic PEC performance and mobilities.

a, The electrochemical epitaxy set-up with the three-electrode configuration for liquid-phase epitaxial growth of Cu2O thin films. b,c, X-ray diffraction patterns (b) and pole figures generated from EBSD (c) for single-crystal epitaxial layers on Si substrates with reflections highlighted in circles. a.u., arbitrary units. d–f, A cross-sectional transmission electron micrograph showing Cu2O(111)/Au(111)/Si(111) layers (d), with close-up images at the Cu2O/Au (f) and Au/Si (e) interfaces, with lattice spacings in agreement with bulk references. Scale bars, 10 nm (d) and 2 nm (e,f). g, PEC responses of SC-Cu2O photocathodes for solar hydrogen evolution under a simulated one-sun condition. The inset shows the layered structure of the Cu2O photocathodes. h, Mott–Schottky plots of SC-Cu2O thin films tested in pH 9 carbonate buffer solution. The carrier densities were calculated based on the slopes of the linear fitting represented by the dotted lines. i–k, Current density–voltage curves of hole-only devices with SC-Cu2O(100) (i), SC-Cu2O(110) (j) and SC-Cu2O(111) (k).

See the science paper for further instructive material with images.

Copper (I) oxide, or cuprous oxide, has been touted as a cheap potential replacement for silicon for years, since it is reasonably effective at capturing sunlight and converting it into electric charge. However, much of that charge tends to get lost, limiting the material’s performance.

“Like other oxide semiconductors, cuprous oxide has its intrinsic challenges,” said co-first author Dr Linfeng Pan from Cambridge’s Department of Chemical Engineering and Biotechnology. “One of those challenges is the mismatch between how deep light is absorbed and how far the charges travel within the material, so most of the oxide below the top layer of material is essentially dead space.”

“For most solar cell materials, it’s defects on the surface of the material that cause a reduction in performance, but with these oxide materials, it’s the other way round: the surface is largely fine, but something about the bulk leads to losses,” said Professor Sam Stranks, who led the research. “This means the way the crystals are grown is vital to their performance.”

To develop cuprous oxides to the point where they can be a credible contender to established photovoltaic materials, they need to be optimised so they can efficiently generate and move electric charges – made of an electron and a positively-charged electron ‘hole’ – when sunlight hits them.

One potential optimisation approach is single-crystal thin films – very thin slices of material with a highly-ordered crystal structure, which are often used in electronics. However, making these films is normally a complex and time-consuming process.

Using thin film deposition techniques, the researchers were able to grow high-quality cuprous oxide films at ambient pressure and room temperature. By precisely controlling growth and flow rates in the chamber, they were able to ‘shift’ the crystals into a particular orientation. Then, using high temporal resolution spectroscopic techniques, they were able to observe how the orientation of the crystals affected how efficiently electric charges moved through the material.

“These crystals are basically cubes, and we found that when the electrons move through the cube at a body diagonal, rather than along the face or edge of the cube, they move an order of magnitude further,” said Pan. “The further the electrons move, the better the performance.”

“Something about that diagonal direction in these materials is magic,” said Stranks. “We need to carry out further work to fully understand why and optimise it further, but it has so far resulted in a huge jump in performance.” Tests of a cuprous oxide photocathode made using this technique showed an increase in performance of more than 70% over existing state-of-the-art electrodeposited oxide photocathodes.

“In addition to the improved performance, we found that the orientation makes the films much more stable, but factors beyond the bulk properties may be at play,” said Pan.

The researchers say that much more research and development is still needed, but this and related families of materials could have a vital role in the energy transition.

“There’s still a long way to go, but we’re on an exciting trajectory,” said Stranks. “There’s a lot of interesting science to come from these materials, and it’s interesting for me to connect the physics of these materials with their growth, how they form, and ultimately how they perform.”

The research was a collaboration with École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne, Nankai University and Uppsala University. The research was supported in part by the European Research Council, the Swiss National Science Foundation, and the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC), part of UK Research and Innovation (UKRI). Sam Stranks is Professor of Optoelectronics in the Department of Chemical Engineering and Biotechnology, and a Fellow of Clare College, Cambridge.

See the full article here .

Comments are invited and will be appreciated, especially if the reader finds any errors which I can correct.

five-ways-keep-your-child-safe-school-shootings

Please help promote STEM in your local schools.

The University of Cambridge (UK) [legally The Chancellor, Masters, and Scholars of the University of Cambridge] is a collegiate public research university in Cambridge, England. Founded in 1209 Cambridge is the second-oldest university in the English-speaking world and the world’s fourth-oldest surviving university. It grew out of an association of scholars who left the University of Oxford (UK) after a dispute with townsfolk. The two ancient universities share many common features and are often jointly referred to as “Oxbridge”.

Cambridge is formed from a variety of institutions which include 31 semi-autonomous constituent colleges and over 150 academic departments, faculties and other institutions organized into six schools. All the colleges are self-governing institutions within the university, each controlling its own membership and with its own internal structure and activities. All students are members of a college. Cambridge does not have a main campus and its colleges and central facilities are scattered throughout the city. Undergraduate teaching at Cambridge is organized around weekly small-group supervisions in the colleges – a feature unique to the Oxbridge system. These are complemented by classes, lectures, seminars, laboratory work and occasionally further supervisions provided by the central university faculties and departments. Postgraduate teaching is provided predominantly centrally.

Cambridge University Press a department of the university is the oldest university press in the world and currently the second largest university press in the world. Cambridge Assessment also a department of the university is one of the world’s leading examining bodies and provides assessment to over eight million learners globally every year. The university also operates eight cultural and scientific museums, including the Fitzwilliam Museum, as well as a botanic garden. Cambridge’s libraries – of which there are 116 – hold a total of around 16 million books, around nine million of which are in Cambridge University Library, a legal deposit library. The university is home to – but independent of – the Cambridge Union – the world’s oldest debating society. The university is closely linked to the development of the high-tech business cluster known as “Silicon Fe”. It is the central member of Cambridge University Health Partners, an academic health science centre based around the Cambridge Biomedical Campus.

By both endowment size and consolidated assets Cambridge is the wealthiest university in the United Kingdom. The central university – excluding colleges – has a total income of over £2.5 billion of which over £600 million is from research grants and contracts. The central university and colleges together possess a combined endowment of over £7 billion and overall consolidated net assets (excluding “immaterial” historical assets) of over £12.5 billion. It is a member of numerous associations and forms part of the ‘golden triangle’ of English universities.

Cambridge has educated many notable alumni including eminent mathematicians, scientists, politicians, lawyers, philosophers, writers, actors, monarchs and heads of state. Nobel laureates, Fields Medalists, Turing Award winners and British prime ministers have been affiliated with Cambridge as students, alumni, faculty or research staff. University alumni have won many Olympic medals.

History

By the late 12th century, the Cambridge area already had a scholarly and ecclesiastical reputation due to monks from the nearby bishopric church of Ely. However, it was an incident at Oxford which is most likely to have led to the establishment of the university: three Oxford scholars were hanged by the town authorities for the death of a woman without consulting the ecclesiastical authorities who would normally take precedence (and pardon the scholars) in such a case; but were at that time in conflict with King John. Fearing more violence from the townsfolk scholars from the University of Oxford started to move away to cities such as Paris, Reading and Cambridge. Subsequently enough scholars remained in Cambridge to form the nucleus of a new university when it had become safe enough for academia to resume at Oxford. In order to claim precedence, it is common for Cambridge to trace its founding to the 1231 charter from Henry III granting it the right to discipline its own members (ius non-trahi extra) and an exemption from some taxes; Oxford was not granted similar rights until 1248.

A bull in 1233 from Pope Gregory IX gave graduates from Cambridge the right to teach “everywhere in Christendom”. After Cambridge was described as a studium generale in a letter from Pope Nicholas IV in 1290 and confirmed as such in a bull by Pope John XXII in 1318 it became common for researchers from other European medieval universities to visit Cambridge to study or to give lecture courses.

Foundation of the colleges

The colleges at the University of Cambridge were originally an incidental feature of the system. No college is as old as the university itself. The colleges were endowed fellowships of scholars. There were also institutions without endowments called hostels. The hostels were gradually absorbed by the colleges over the centuries; but they have left some traces, such as the name of Garret Hostel Lane.

Hugh Balsham, Bishop of Ely, founded Peterhouse – Cambridge’s first college in 1284. Many colleges were founded during the 14th and 15th centuries but colleges continued to be established until modern times. There was a gap of 204 years between the founding of Sidney Sussex in 1596 and that of Downing in 1800. The most recently established college is Robinson built in the late 1970s. However, Homerton College only achieved full university college status in March 2010 making it the newest full college (it was previously an “Approved Society” affiliated with the university).

In medieval times many colleges were founded so that their members would pray for the souls of the founders and were often associated with chapels or abbeys. The colleges’ focus changed in 1536 with the Dissolution of the Monasteries. Henry VIII ordered the university to disband its Faculty of Canon Law and to stop teaching “scholastic philosophy”. In response, colleges changed their curricula away from canon law and towards the classics; the Bible; and mathematics.

Nearly a century later the university was at the centre of a Protestant schism. Many nobles, intellectuals and even commoners saw the ways of the Church of England as too similar to the Catholic Church and felt that it was used by the Crown to usurp the rightful powers of the counties. East Anglia was the centre of what became the Puritan movement. In Cambridge the movement was particularly strong at Emmanuel; St Catharine’s Hall; Sidney Sussex; and Christ’s College. They produced many “non-conformist” graduates who, greatly influenced by social position or preaching left for New England and especially the Massachusetts Bay Colony during the Great Migration decade of the 1630s. Oliver Cromwell, Parliamentary commander during the English Civil War and head of the English Commonwealth (1649–1660), attended Sidney Sussex.

Modern period

After the Cambridge University Act formalized the organizational structure of the university the study of many new subjects was introduced e.g. theology, history and modern languages. Resources necessary for new courses in the arts architecture and archaeology were donated by Viscount Fitzwilliam of Trinity College who also founded the Fitzwilliam Museum. In 1847 Prince Albert was elected Chancellor of the University of Cambridge after a close contest with the Earl of Powis. Albert used his position as Chancellor to campaign successfully for reformed and more modern university curricula, expanding the subjects taught beyond the traditional mathematics and classics to include modern history and the natural sciences. Between 1896 and 1902 Downing College sold part of its land to build the Downing Site with new scientific laboratories for anatomy, genetics, and Earth sciences. During the same period the New Museums Site was erected including the Cavendish Laboratory which has since moved to the West Cambridge Site and other departments for chemistry and medicine.

The University of Cambridge began to award PhD degrees in the first third of the 20th century. The first Cambridge PhD in mathematics was awarded in 1924.

In the First World War 13,878 members of the university served and 2,470 were killed. Teaching and the fees it earned came almost to a stop and severe financial difficulties followed. As a consequence, the university first received systematic state support in 1919 and a Royal Commission appointed in 1920 recommended that the university (but not the colleges) should receive an annual grant.

Following the Second World War the university saw a rapid expansion of student numbers and available places; this was partly due to the success and popularity gained by many Cambridge scientists.