From Washington University in St. Louis

5.21.24

Chris Woolston

chrisw@wustl.edu

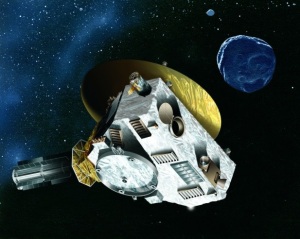

In a paper published in the journal Icarus, WashU graduate student Alex Nguyen used mathematical models and images from the New Horizons spacecraft to take a closer look at the ocean that likely covers Pluto beneath a thick shell of nitrogen, methane and water ice. (Image: NASA)

An ocean of liquid water deep beneath the icy surface of Pluto is coming into focus thanks to new calculations by Alex Nguyen, a graduate student in earth, environmental and planetary sciences in Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis.

In a paper published in the journal Icarus, Nguyen used mathematical models and images from the New Horizons spacecraft that passed by Pluto in 2015 to take a closer look at the ocean that likely covers the planet beneath a thick shell of nitrogen, methane and water ice.

Patrick McGovern of the Lunar and Planetary Institute in Houston was a co-author of the paper.

For many decades, planetary scientists assumed that Pluto could not support an ocean. The surface temperature is about -220 C, a temperature so cold even gases like nitrogen and methane freeze solid. Water shouldn’t have a chance.

“Pluto is a small body,” said Nguyen, who is conducting his PhD research at Washington University as an Olin Chancellor’s Fellow and a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellow. “It should have lost almost all of its heat shortly after it was formed, so basic calculations would suggest that it’s frozen solid to its core.”

But in recent years, prominent scientists including William B. McKinnon, a professor of earth, environmental and planetary science in Arts & Sciences, have gathered evidence suggesting Pluto likely contains an ocean of liquid water beneath the ice. That inference came from several lines of evidence, including Pluto’s cryovolcanoes that spew ice and water vapor. Although there is still some debate, “it’s now generally accepted that Pluto has an ocean,” Nguyen said.

The new study probes the ocean in greater detail, even if it’s far too deep below the ice for scientists to ever see. Nguyen and McGovern created mathematical models to explain the cracks and bulges in the ice covering Pluto’s Sputnik Platina Basin, the site of a meteor collision billions of years ago. Their calculations suggest the ocean in this area exists beneath a shell of water ice 40 to 80 km thick, a blanket of protection that likely keeps the inner ocean from freezing solid.

They also calculated the likely density or salinity of the ocean based on the fractures in the ice above. They estimate Pluto’s ocean is, at most, about 8% denser than seawater on Earth, or roughly the same as Utah’s Great Salt Lake. If you could somehow get to Pluto’s ocean, you could effortlessly float.

As Nguyen explained, that level of density would explain the abundance of fractures seen on the surface. If the ocean was significantly less dense, the ice shell would collapse, creating many more fractures than actually observed. If the ocean was much denser, there would be fewer fractures. “We estimated a sort of Goldilocks zone where the density and shell thickness is just right,” he said.

Space agencies have no plans to return to Pluto any time soon, so many of its mysteries will remain for future generations of researchers. Whether it’s called a planet, a planetoid, or merely one of many objects in the outer reaches of the solar system, it’s worth studying, Nguyen said. “From my perspective, it’s a planet.”

See the full article here .

Comments are invited and will be appreciated, especially if the reader finds any errors which I can correct.

five-ways-keep-your-child-safe-school-shootings

Please help promote STEM in your local schools.

Washington University in St. Louis is a private research university in Greater St. Louis with its main campus (Danforth) mostly in unincorporated St. Louis County, Missouri, and Clayton, Missouri. It also has a West Campus in Clayton, North Campus in the West End neighborhood of St. Louis, Missouri, and Medical Campus in the Central West End neighborhood of St. Louis, Missouri.

Founded in 1853 and named after George Washington, the university has students and faculty from all 50 U.S. states and more than 120 countries. Washington University is composed of seven graduate and undergraduate schools that encompass a broad range of academic fields. To prevent confusion over its location, the Board of Trustees added the phrase “in St. Louis” in 1976. Washington University is a member of the Association of American Universities and is classified among “R1: Doctoral Universities – Very high research activity”.

Nobel laureates in economics, physiology and medicine, chemistry, and physics have been affiliated with Washington University. Ten having done the major part of their pioneering research at the university. Clarivate Analytics ranked Washington University among the highest in the world for most cited researchers. The university also receives a high amount of National Institutes of Health medical research grants among medical schools.

Washington University was conceived by 17 St. Louis business, political, and religious leaders concerned by the lack of institutions of higher learning in the Midwest. Missouri State Senator Wayman Crow and Unitarian minister William Greenleaf Eliot, grandfather of the poet T.S. Eliot, led the effort.

The university’s first chancellor was Joseph Gibson Hoyt. Crow secured the university charter from the Missouri General Assembly in 1853, and Eliot was named President of the Board of Trustees. Early on, Eliot solicited support from members of the local business community, including John O’Fallon, but Eliot failed to secure a permanent endowment. Washington University is unusual among major American universities in not having had a prior financial endowment. The institution had no backing of a religious organization, single wealthy patron, or earmarked government support.

During the three years following its inception, the university bore three different names. The board first approved “Eliot Seminary,” but William Eliot was uncomfortable with naming a university after himself and objected to the establishment of a seminary, which would implicitly be charged with teaching a religious faith. He favored a nonsectarian university. In 1854, the Board of Trustees changed the name to “Washington Institute” in honor of George Washington, and because the charter was coincidentally passed on Washington’s birthday, February 22. Naming the university after the nation’s first president, only seven years before the American Civil War and during a time of bitter national division, was no coincidence. During this time of conflict, Americans universally admired George Washington as the father of the United States and a symbol of national unity. The Board of Trustees believed that the university should be a force of unity in a strongly divided Missouri. In 1856, the university amended its name to “Washington University.” The university amended its name once more in 1976, when the Board of Trustees voted to add the suffix “in St. Louis” to distinguish the university from the over two dozen other universities bearing Washington’s name.

Although chartered as a university, for many years Washington University functioned primarily as a night school located on 17th Street and Washington Avenue in the heart of downtown St. Louis. Owing to limited financial resources, Washington University initially used public buildings. Classes began on October 22, 1854, at the Benton School building. At first the university paid for the evening classes, but as their popularity grew, their funding was transferred to the St. Louis Public Schools. Eventually the board secured funds for the construction of Academic Hall and a half dozen other buildings. Later the university divided into three departments: the Manual Training School, Smith Academy, and the Mary Institute.

In 1867, the university opened the first private nonsectarian law school west of the Mississippi River. By 1882, Washington University had expanded to numerous departments, which were housed in various buildings across St. Louis. Medical classes were first held at Washington University in 1891 after the St. Louis Medical College decided to affiliate with the university, establishing the School of Medicine. During the 1890s, Robert Sommers Brookings, the president of the Board of Trustees, undertook the tasks of reorganizing the university’s finances, putting them onto a sound foundation, and buying land for a new campus.

In 1896, Holmes Smith, professor of Drawing and History of Art, designed what would become the basis for the modern-day university seal. The seal is made up of elements from the Washington family coat of arms, and the symbol of Louis IX, whom the city is named after.

Washington University spent its first half century in downtown St. Louis bounded by Washington Ave., Lucas Place, and Locust Street. By the 1890s, owing to the dramatic expansion of the Medical School and a new benefactor in Robert Brookings, the university began to move west. The university board of directors began a process to find suitable ground and hired the landscape architecture firm Olmsted, Olmsted & Eliot of Boston. A committee of Robert S. Brookings, Henry Ware Eliot, and William Huse found a site of 103 acres (41.7 ha) just beyond Forest Park, located west of the city limits in St. Louis County. The elevation of the land was thought to resemble the Acropolis and inspired the nickname of “Hilltop” campus, renamed the Danforth campus in 2006 to honor former chancellor William H. Danforth.

In 1899, the university opened a national design contest for the new campus. The renowned Philadelphia firm Cope & Stewardson (same architects who designed a large part of The University of Pennsylvania and Princeton University) won unanimously with its plan for a row of Collegiate Gothic quadrangles inspired by The University of Oxford (UK) and The University of Cambridge (UK). The cornerstone of the first building, Busch Hall, was laid on October 20, 1900. The construction of Brookings Hall, Ridgley, and Cupples began shortly thereafter. The school delayed occupying these buildings until 1905 to accommodate the 1904 World’s Fair and Olympics. The delay allowed the university to construct ten buildings instead of the seven originally planned. This original cluster of buildings set a precedent for the development of the Danforth Campus; Cope & Stewardson’s original plan and its choice of building materials have, with few exceptions, guided the construction and expansion of the Danforth Campus to the present day.

By 1915, construction of a new medical complex was completed on Kingshighway in what is now St. Louis’s Central West End. Three years later, Washington University admitted its first women medical students.

In 1922, a young physics professor, Arthur Holly Compton, conducted a series of experiments in the basement of Eads Hall that demonstrated the “particle” concept of electromagnetic radiation. Compton’s discovery, known as the “Compton Effect,” earned him the Nobel Prize in physics in 1927.

During World War II, as part of the Manhattan Project, a cyclotron at Washington University was used to produce small quantities of the newly discovered element plutonium via neutron bombardment of uranium nitrate hexahydrate. The plutonium produced there in 1942 was shipped to the Metallurgical Laboratory Compton had established at The University of Chicago where Glenn Seaborg’s team used it for extraction, purification, and characterization studies of the exotic substance.

After working for many years at The University of Chicago, Arthur Holly Compton returned to St. Louis in 1946 to serve as Washington University’s ninth chancellor. Compton reestablished the Washington University football team, making the declaration that athletics were to be henceforth played on a “strictly amateur” basis with no athletic scholarships. Under Compton’s leadership, enrollment at the university grew dramatically, fueled primarily by World War II veterans’ use of their GI Bill benefits.

In 1947, Gerty Cori, a professor at School of Medicine, became the first woman to win a Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

Professors Carl and Gerty Cori became Washington University’s fifth and sixth Nobel laureates for their discovery of how glycogen is broken down and resynthesized in the body.

The process of desegregation at Washington University began in 1947 with the School of Medicine and the School of Social Work. During the mid and late 1940s, the university was the target of critical editorials in the local African American press, letter-writing campaigns by churches and the local Urban League, and legal briefs by the NAACP intended to strip its tax-exempt status. In spring 1949, a Washington University student group, the Student Committee for the Admission of Negroes (SCAN), began campaigning for full racial integration. In May 1952, the Board of Trustees passed a resolution desegregating the school’s undergraduate divisions.

During the latter half of the 20th century, Washington University transitioned from a strong regional university to a national research institution. In 1957, planning began for the construction of the “South 40,” a complex of modern residential halls which primarily house Freshmen and some Sophomore students. With the additional on-campus housing, Washington University, which had been predominantly a “streetcar college” of commuter students, began to attract a more national pool of applicants. By 1964, over two-thirds of incoming students came from outside the St. Louis area.

In 1971, the Board of Trustees appointed Chancellor William Henry Danforth, who guided the university through the social and financial crises of the 1970s and strengthened the university’s often strained relationship with the St. Louis community. During his 24-year chancellorship, Danforth significantly improved the School of Medicine, established 70 new faculty chairs, secured a $1.72 billion endowment, and tripled the amount of student scholarships.

In 1995, Mark S. Wrighton, former Provost at The Massachusetts Institute of Technology, was elected the university’s 14th chancellor. During Chancellor Wrighton’s tenure undergraduate applications to Washington University more than doubled. Since 1995, the university has added more than 190 endowed professorships, revamped its Arts & Sciences curriculum, and completed more than 30 new buildings.

The growth of Washington University’s reputation coincided with a series of record-breaking fund-raising efforts during the last three decades. From 1983 to 1987, the Alliance for Washington University campaign raised $630.5 million, which was then the most successful fund-raising effort in national history. From 1998 to 2004, the Campaign for Washington University raised $1.55 billion, which was applied to additional scholarships, professorships, and research initiatives.

In 2002, Washington University co-founded the Cortex Innovation Community in St. Louis’s Midtown neighborhood. Cortex is the largest innovation hub in the midwest, home to offices of Square, Microsoft, Aon, Boeing, and Centene. The innovation hub has generated more than 3,800 tech jobs in 14 years.

In 2005, Washington University founded the McDonnell International Scholars Academy, an international network of premier research universities, with an initial endowment gift of $10 million from John F. McDonnell. The academy, which selects scholars from 35 partner universities around the world, was created with the intent to develop a cohort of future leaders, strengthen ties with top foreign universities, and promote global awareness and social responsibility.

In 2019, Washington University unveiled a $360 million campus transformation project known as the East End Transformation. The transformation project, built on the original 1895 campus plan by Olmsted, Olmsted & Eliot, encompassed 18 acres of the Danforth Campus, adding five new buildings, expanding the university’s Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum, relocating hundreds of surface parking spaces underground, and creating an expansive new park.

In June 2019, Andrew D. Martin, former dean of the College of Literature, Science, and the Arts at The University of Michigan, was elected the university’s 15th chancellor. On the day of his inauguration, Chancellor Martin announced the WashU Pledge, a financial aid program allowing full-time Missouri and southern Illinois students who are Pell Grant-eligible or from families with annual incomes of $75,000 or less to attend the university cost-free.

Washington University’s undergraduate program is ranked very highly in the nation in U.S. News & World Report National Universities ranking, and very highly by The Wall Street Journal. The university is ranked very highly in the world by The Academic Ranking of World Universities. Undergraduate admission to Washington University is characterized by The Carnegie Foundation and U.S. News & World Report as “most selective”. The Princeton Review, gave the university an admissions selectivity rating of 99 out of 99. Acceptance rates for the class of 2024 (those entering in the fall of 2020) was 12.8%, with students selected from more than 27,900 applications. Of students admitted, 92 percent were in the top 10 percent of their class.

The Princeton Review ranks Washington University very highly for Best College Dorms and for Best College Food, Best-Run Colleges, and Best Financial Aid. Niche lists the university very highly for architecture and college campus and college dorms in the United States. The Washington University School of Medicine was ranked very highly for research by U.S. News & World Report and has been listed among the top ten medical schools since the rankings were first published. Additionally, U.S. News & World Report ranks the university’s genetics and physical therapy very highly. QS World University Rankings ranks Washington University very highly in the world for anatomy and physiology. Olin Business School is ranked very highly in the The Poets & Quants MBA Program. Washington University is also recognized very highly as a university employer in the country by Forbes.

Washington University has been named one of the “25 New Ivies” by Newsweek and has also been called a “Hidden Ivy”.

A study ranked Washington University very highly in the country for income inequality, when measured as the ratio of number of students from the top 1% of the income scale to number of students from the bottom 60% of the income scale. About 22% of Washington University’s students came from the top 1%, while only about 6% came from the bottom 60%. In 2015, university administration announced plans to increase the number of Pell-eligible recipients on campus from 6% to 13%, and a large number of the university’s student body was eligible for Pell Grants. In October 2019, then newly inaugurated Chancellor Andrew D. Martin announced the WashU Pledge, a financial aid program that provides a free undergraduate education to all full-time Missouri and Southern Illinois students who are Pell Grant-eligible or from families with annual incomes of $75,000 or less. The university’s refusal to divest from the fossil fuel industry has drawn controversy in recent years.

Research

Virtually all faculty members at Washington University engage in academic research, offering opportunities for both undergraduate and graduate students across the university’s seven schools. Known for its interdisciplinary and departmental collaboration, many of Washington University’s research centers and institutes are collaborative efforts between many areas on campus. More than 60% of undergraduates are involved in faculty research across all areas; it is an institutional priority for undergraduates to be allowed to participate in advanced research. According to the Center for Measuring University Performance, it is considered very high among the top 10 private research universities in the nation. A dedicated Office of Undergraduate Research is located on the Danforth Campus and serves as a resource to post research opportunities, advise students in finding appropriate positions matching their interests, publish undergraduate research journals, and award research grants to make it financially possible to perform research.

According to the National Science Foundation, Washington University spends over $900 million on research and development, ranking it very highly in the nation. The university has over 150 National Institutes of Health funded inventions, with many of them licensed to private companies. Governmental agencies and non-profit foundations such as the NIH, Department of Defense, National Science Foundation, and National Aeronautics Space Agency provide the majority of research grant funding, with Washington University being among the top recipients in NIH grants from year-to-year. Nearly 80% of NIH grants to institutions in the state of Missouri go to Washington University alone. Washington University and its Medical School play a large part in the Human Genome Project, where it contributes approximately 25% of the finished sequence. The Genome Sequencing Center has decoded the genome of many animals, plants, and cellular organisms, including the platypus, chimpanzee, cat, and corn.

NASA hosts its Planetary Data System Geosciences Node on the campus of Washington University. Professors, students, and researchers have been heavily involved with many unmanned missions to Mars. Professor Raymond Arvidson has been deputy principal investigator of the Mars Exploration Rover mission and co-investigator of the Phoenix lander robotic arm.

Washington University professor Joseph Lowenstein, with the assistance of several undergraduate students, has been involved in editing, annotating, making a digital archive of the first publication of poet Edmund Spenser’s collective works in 100 years. A large grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities has been given to support this ambitious project centralized at Washington University with support from other colleges in the United States.

In 2019, Folding@Home, a distributed computing project for performing molecular dynamics simulations of protein dynamics, was moved to Washington University School of Medicine from Stanford University. It is currently housed at The University of Pennsylvania. The project uses the idle CPU time of personal computers owned by volunteers to conduct protein folding research. Folding@home’s research is primarily focused on biomedical problems such as Alzheimer’s disease, Cancer, Coronavirus disease, and Ebola virus disease. In April 2020, Folding@home became the world’s first exaFLOP computing system with a peak performance of 1.5 exaflops, making it more than seven times faster than the then world’s fastest supercomputer, Summit, and more powerful than the top 100 supercomputers in the world, combined.