4.30.24

Celia Luterbacher

Guillaume Bellegarda, Milad Shafiee and Auke Ijspeert. 2024 EPFL/Jamani Caillet – CC-BY-SA 4.0

A four-legged robot trained with machine learning by EPFL researchers has learned to avoid falls by spontaneously switching between walking, trotting, and pronking – a milestone for roboticists as well as biologists interested in animal locomotion.

With the help of a form of machine learning called deep reinforcement learning (DRL), the EPFL robot notably learned to transition from trotting to pronking – a leaping, arch-backed gait used by animals like springbok and gazelles – to navigate a challenging terrain with gaps ranging from 14-30cm. The study, led by the BioRobotics Laboratory in EPFL’s School of Engineering, offers new insights into why and how such gait transitions occur in animals.

“Previous research has introduced energy efficiency and musculoskeletal injury avoidance as the two main explanations for gait transitions. More recently, biologists have argued that stability on flat terrain could be more important. But animal and robotic experiments have shown that these hypotheses are not always valid, especially on uneven ground,” says PhD student Milad Shafiee, first author on a paper published in Nature Communications.

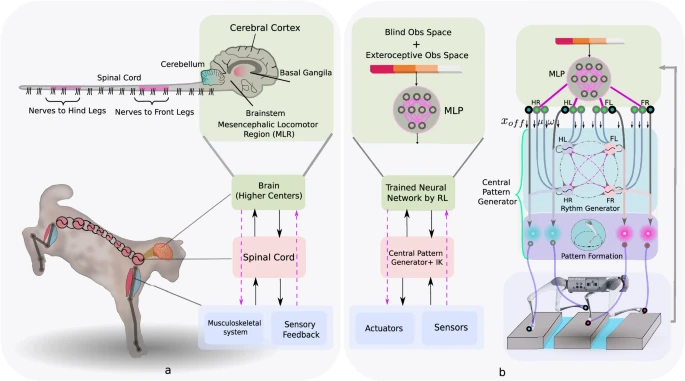

Fig. 1: Proposed learning architecture.

a To model locomotion control, we consider three main interacting layers: the brain (higher centers), the spinal cord, and the body and sensory feedback modules. Higher neural centers (such as the brainstem, basal ganglia, cerebellum, and motor cortex) send descending drive signals to modulate the spinal circuits, and/or directly interact with lower modules (body and sensory feedback). b We represent these higher neural centers with a multilayer perceptron (MLP) with three hidden layers of [512, 256, 128] neurons with elu activation. To represent the Central Pattern Generator in the spinal cord, we use nonlinear amplitude-controlled phase oscillators for modeling the Rhythm Generator (RG) layer, whose outputs are mapped to foot positions and then motor commands with inverse kinematics (IK) through a Pattern Formation (PF) layer. FR, FL, HR, and HL stand for front right, front left, hind right, and hind left, respectively. The brain figure in (a) has been re-drawn with inspiration from Grillner et al.1* (CC BY 4.0).

*Science paper reference.

See the science paper for further instructive material with images.

Shafiee and co-authors Guillaume Bellegarda and BioRobotics Lab head Auke Ijspeert were therefore interested in a new hypothesis for why gait transitions occur: viability, or fall avoidance. To test this hypothesis, they used DRL to train a quadruped robot to cross various terrains. On flat terrain, they found that different gaits showed different levels of robustness against random pushes, and that the robot switched from a walk to a trot to maintain viability, just as quadruped animals do when they accelerate. And when confronted with successive gaps in the experimental surface, the robot spontaneously switched from trotting to pronking to avoid falls. Moreover, viability was the only factor that was improved by such gait transitions.

“We showed that on flat terrain and challenging discrete terrain, viability leads to the emergence of gait transitions, but that energy efficiency is not necessarily improved,” Shafiee explains. “It seems that energy efficiency, which was previously thought to be a driver of such transitions, may be more of a consequence. When an animal is navigating challenging terrain, it’s likely that its first priority is not falling, followed by energy efficiency.”

A bio-inspired learning architecture

To model locomotion control in their robot, the researchers considered the three interacting elements that drive animal movement: the brain, the spinal cord, and sensory feedback from the body. They used DRL to train a neural network to imitate the spinal cord’s transmission of brain signals to the body as the robot crossed an experimental terrain. Then, the team assigned different weights to three possible learning goals: energy efficiency, force reduction, and viability. A series of computer simulations revealed that of these three goals, viability was the only one that prompted the robot to automatically – without instruction from the scientists – change its gait.

The team emphasizes that these observations represent the first learning-based locomotion framework in which gait transitions emerge spontaneously during the learning process, as well as the most dynamic crossing of such large consecutive gaps for a quadrupedal robot.

“Our bio-inspired learning architecture demonstrated state-of-the-art quadruped robot agility on the challenging terrain,” Shafiee says.

The researchers aim to expand on their work with additional experiments that place different types of robots in a wider variety of challenging environments. In addition to further elucidating animal locomotion, they hope that ultimately, their work will enable the more widespread use of robots for biological research, reducing reliance on animal models and the associated ethics concerns.

See the full article here.

Comments are invited and will be appreciated, especially if the reader finds any errors which I can correct.

five-ways-keep-your-child-safe-school-shootings

Please help promote STEM in your local schools.

The Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Lausanne [EPFL-École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne] (CH) is a research institute and university in Lausanne, Switzerland, that specializes in natural sciences and engineering. It is one of the two Swiss Federal Institutes of Technology, and it has three main missions: education, research and technology transfer.

The QS World University Rankings ranks EPFL(CH) very high, whereas Times Higher Education World University Rankings ranks EPFL(CH) as one of the world’s best schools for Engineering and Technology.

EPFL(CH) is located in the French-speaking part of Switzerland; the sister institution in the German-speaking part of Switzerland is The Swiss Federal Institute of Technology ETH Zürich [Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule Zürich] (CH). Associated with several specialized research institutes, the two universities form The Domain of the Swiss Federal Institutes of Technology (ETH Domain) [ETH-Bereich; Domaine des Écoles Polytechniques Fédérales] (CH) which is directly dependent on the Federal Department of Economic Affairs, Education and Research. In connection with research and teaching activities, EPFL(CH) operates a nuclear reactor CROCUS; a Tokamak Fusion reactor; a Blue Gene/Q Supercomputer; and P3 bio-hazard facilities.

ETH Zürich, EPFL (Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Lausanne) [École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne](CH), and four associated research institutes form The Domain of the Swiss Federal Institutes of Technology (ETH Domain) [ETH-Bereich; Domaine des Écoles polytechniques fédérales] (CH) with the aim of collaborating on scientific projects.

The roots of modern-day EPFL(CH) can be traced back to the foundation of a private school under the name École Spéciale de Lausanne in 1853 at the initiative of Lois Rivier, a graduate of the École Centrale Paris (FR) and John Gay the then professor and rector of the Académie de Lausanne. At its inception it had only 11 students and the offices were located at Rue du Valentin in Lausanne. In 1869, it became the technical department of the public Académie de Lausanne. When the Académie was reorganized and acquired the status of a university in 1890, the technical faculty changed its name to École d’Ingénieurs de l’Université de Lausanne. In 1946, it was renamed the École polytechnique de l’Université de Lausanne (EPUL). In 1969, the EPUL was separated from the rest of the University of Lausanne and became a federal institute under its current name. EPFL(CH), like ETH Zürich (CH), and it is thus directly controlled by the Swiss federal government. In contrast, all other universities in Switzerland are controlled by their respective cantonal governments. EPFL(CH) has started to develop into the field of life sciences. It absorbed the Swiss Institute for Experimental Cancer Research (ISREC) in 2008.

In 1946, there were 360 students. In 1969, EPFL(CH) had 1,400 students and 55 professors. In the past two decades the university has grown rapidly and over 14,000 people study or work on campus, about 10,000 of these being Bachelor, Master or PhD students. The environment at modern day EPFL(CH) is highly international with the school attracting students and researchers from all over the world. More than 125 countries are represented on the campus and the university has two official languages, French and English.

Organization

EPFL is organized into eight schools, themselves formed of institutes that group research units (laboratories or chairs) around common themes:

School of Basic Sciences

Institute of Mathematics

Institute of Chemical Sciences and Engineering

Institute of Physics

European Centre of Atomic and Molecular Computations

Bernoulli Center

Biomedical Imaging Research Center

Interdisciplinary Center for Electron Microscopy

MPG-EPFL Centre for Molecular Nanosciences and Technology

Swiss Plasma Center

Laboratory of Astrophysics

School of Engineering

Institute of Electrical Engineering

Institute of Mechanical Engineering

Institute of Materials

Institute of Microengineering

Institute of Bioengineering

School of Architecture, Civil and Environmental Engineering

Institute of Architecture

Civil Engineering Institute

Institute of Urban and Regional Sciences

Environmental Engineering Institute

School of Computer and Communication Sciences

Algorithms & Theoretical Computer Science

Artificial Intelligence & Machine Learning

Computational Biology

Computer Architecture & Integrated Systems

Data Management & Information Retrieval

Graphics & Vision

Human-Computer Interaction

Information & Communication Theory

Networking

Programming Languages & Formal Methods

Security & Cryptography

Signal & Image Processing

Systems

School of Life Sciences

Bachelor-Master Teaching Section in Life Sciences and Technologies

Brain Mind Institute

Institute of Bioengineering

Swiss Institute for Experimental Cancer Research

Global Health Institute

Ten Technology Platforms & Core Facilities (PTECH)

Center for Phenogenomics

NCCR Synaptic Bases of Mental Diseases

College of Management of Technology

Swiss Finance Institute at EPFL

Section of Management of Technology and Entrepreneurship

Institute of Technology and Public Policy

Institute of Management of Technology and Entrepreneurship

Section of Financial Engineering

College of Humanities

Human and social sciences teaching program

EPFL Middle East

Section of Energy Management and Sustainability

In addition to the eight schools there are seven closely related institutions

Swiss Cancer Centre

Center for Biomedical Imaging (CIBM)

Centre for Advanced Modelling Science (CADMOS)

École Cantonale d’art de Lausanne (ECAL)

Campus Biotech

Wyss Center for Bio- and Neuro-engineering

Swiss National Supercomputing Centre