From The University of Leicester (UK)

4.16.24

Evidence from the fragments of a destroyed asteroid suggests that the shift in the positions of the giant planets in our Solar System billions of years ago happened between 60-100 million years after Solar System’s formation and could have been key to the formation of our Moon.

Space scientists led by the University of Leicester have combined evidence from simulations, observations and analysis of meteorites to recreate the orbital instability caused as the giant planets of our Solar System moved into their current locations, known for 20 years as the Nice model.

Fig. 1. Schematic diagram of the preferred scenario.

Red circles are planetesimals (and their fragments) from the terrestrial planet region. The black solid curves roughly denote the boundary of the current asteroid inner main belt. Eccentricity increases from bottom to top. Each panel shows the proposed evolution of the inner Solar System at different time ranges: (A) Formation and cooling of the EL planetesimal in the terrestrial planet region before 60 Myr after Solar System formation. In this period, the terrestrial planets began scattering planetesimals to orbits with high eccentricity and semimajor axes that correspond to the asteroid main belt. (B) Between 60 and 100 Myr, the EL planetesimal was destroyed by an impact in the terrestrial planet region. At least one fragment (the Athor family progenitor) was scattered by the terrestrial planets into the scattered disk, as in (A), then the giant planet instability implanted it into the inner main belt by decreasing its eccentricity. (C) A few tens of millions of years after the giant planet instability occurred, a giant impact between the planetary embryo Theia and proto-Earth formed the Moon. (D) The Athor family progenitor experienced another impact event that formed the Athor family at ~1500 Myr.

The findings are published today (16 April) in the journal Science and presented at the European Geological Union General Assembly in Vienna.

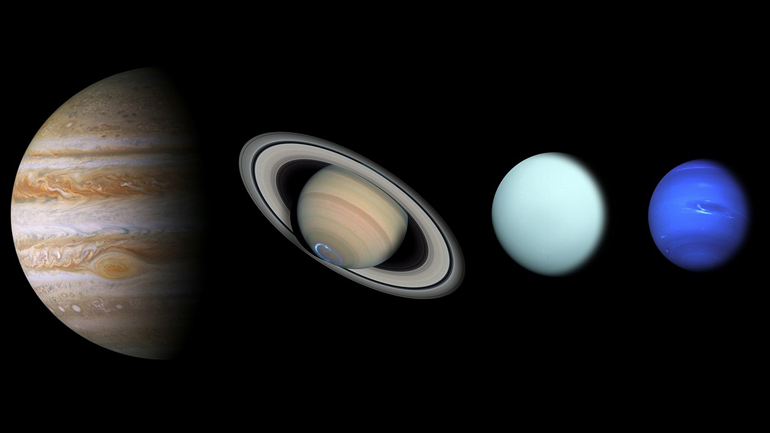

At the beginning of the Solar System, the giant planets – Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune – had more circular and more compact orbits then they do today. Previous research has established that an orbital instability in the Solar System changed that orbital configuration and caused smaller planetesimals to be dispersed. Many of these collided with the inner terrestrial planets, in what scientists have termed the Late Heavy Bombardment.

Lead author Dr Chrysa Avdellidou from the University of Leicester School of Physics and Astronomy said: “The question is, when did it happen? The orbits of these planets destabilised due to some dynamical processes and then took their final positions that we see today. Each timing has a different implication, and it has been a great matter of debate in the community.

“What we have tried to do with this work is to not only do a pure dynamical study, but combine different types of studies, linking observations, dynamical simulations and studies of meteorites.”

They focused on a type of meteorite known as enstatite chondrites, which have a very similar composition to Earth and very similar isotopic ratios, which means they were formed in our neighbourhood. By making spectroscopic observations using ground-based telescopes, they linked those meteorites to their source: a family of fragments in the asteroid belt known as Athor. This suggests that Athor was originally much larger and formed closer to the Sun and that it suffered a collision that reduced its size out of the asteroid belt.

To explain how Athor ended up in the asteroid belt, the scientists tested various scenarios using dynamical simulations, concluding that the most likely explanation was the gravitational instability that shifted the giant planets to their current orbits. Analysis of the meteorites showed that this occurred no earlier than 60 million years after the Solar System began to form. Previous evidence from asteroids in Jupiter’s orbit has also put constraints on how late this event occurred, with the scientists concluding that the gravitational instability must have occurred between 60 and 100 million years after the birth of the Solar System, 4.56 billion of years ago.

Previous evidence has shown that Earth’s moon was formed during this period, with one hypothesis being that a planetesimal known as Theia collided with Earth and debris from that collision formed the Moon.

Timing of the orbital instability is important as it determines when some of the familiar features of our Solar System would develop – and may even have had an impact on the habitability of our planet.

Dr Avdellidou adds: “It’s like you have a puzzle, you understand that something should have happened and you try to put events in the correct order to make the picture that you see today. The novelty with the study is that we are not only doing pure dynamical simulations, or only experiments, or only telescopic observations.

“There were once five inner planets in our Solar System and not four, so that could have implications for other things, like how we form habitable planets. Questions like, when exactly objects came delivering volatile and organics to our planet to Earth and Mars?”

Marco Delbo, co-author of the study and Director of Research at Nice Observatory in France, said: “The timing is very important because our solar system at the beginning was populated by a lot of planetesimals. And the instability clears them, so if that happens 10 million years after the beginning of the solar system you clear the planetesimals immediately, whereas if you do it after 60 million years you have more time to bring materials to Earth and Mars.”

See the full article here .

Comments are invited and will be appreciated, especially if the reader finds any errors which I can correct.

five-ways-keep-your-child-safe-school-shootings

Please help promote STEM in your local schools.

The University of Leicester (UK) is a public research university based in Leicester, England. The main campus is south of the city centre, adjacent to Victoria Park.

The university has established itself as a leading research-led university and has been named University of the Year by the Times Higher Education. The University of Leicester is also the only university ever to have won a Times Higher Education award in seven consecutive years. The university ranks very high in The Complete University Guide and in The Guardian. The QS World University Rankings also placed Leicester very high in the UK for research citations.

The university is most famous for the invention of genetic fingerprinting and for the discovery of the remains of King Richard III.

The first serious suggestions for a university in Leicester began with the Leicester Literary and Philosophical Society (founded at a time when “philosophical” broadly meant what “scientific” means today). With the success of Owen’s College in Manchester, and the establishment of The University of Birmingham (UK) in 1900, and then of The University of Nottingham (UK), it was thought that Leicester ought to have a university college too. From the mid-19th century to the mid-20th century university colleges could not award degrees and had to be associated with universities that had degree-giving powers. Most students at university colleges took examinations set by The University of London (UK).

In the late 19th century, the co-presidents of the Leicester Literary and Philosophical Society, the Revered James Went, headmaster of the Wyggeston Boys’ School, and J. D. Paul, regularly called for the establishment of a university college. However, no private donations were forthcoming, and the Corporation of Leicester was busy funding the School of Art and the Technical School. The matter was brought up again by Dr Astley V. Clarke (1870–1945) in 1912. Born in Leicester in 1870, he had been educated at Wyggeston Grammar School and The University of Cambridge (UK) before receiving medical training at Guy’s Hospital. He was the new President of the Literary and Philosophy society. Reaction was mixed, with some saying that Leicester’s relatively small population would mean a lack of demand. With the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, talk of a university college subsided. In 1917 The Leicester Daily Post urged in an editorial that something of more practical utility than memorials ought to be created to commemorate the war dead. With the ending of the war both The Post and its rival The Leicester Mail encouraged donations to form the university college. Some suggested that Leicester should join forces with Nottingham, Sutton Bonington and Loughborough to create a federal university college of the East Midlands, but nothing came of this proposal.

The old asylum building had often been suggested as a site for the new university, and after it was due to be finished being used as a hospital for the wounded, Astley Clarke was keen to urge the citizens and local authorities to buy it. Fortunately, Clarke quickly learned the building had already been bought by Thomas Fielding Johnson, a wealthy philanthropist who owned a worsted manufacturing business. He had bought 37 acres of land for £40,000 and intended not only to house the college, but also the boys’ and girls’ grammar schools. Further donations soon topped £100,000: many were given in memory of loved ones lost during the war, while others were for those who had taken part and survived. King George V gave his blessing to the scheme after a visit to the town in 1919.

Talk turned to the curriculum with many arguing that it should focus on Leicester’s chief industries hosiery, boots and shoes. Others had higher hopes than just technical training. The education acts of 1902 and 1918, which brought education to the masses was also thought to have increased the need for a college, not least to train the new teachers that were needed. Talk of a federal university soured and the decision was for Leicester to become a stand-alone college. In 1920, the college appointed its first official. W. G. Gibbs, a long-standing supporter of the college while editor of The Leicester Daily Post, was nominated as Secretary. On 9 May 1921, Dr R. F. Rattray (1886–1967) was appointed principal, aged 35. Rattray was an impressive academic. Having gained a first class English degree at The University of Glasgow (SCT), he studied at Manchester College, The University of Oxford (UK). He then studied in Germany, and secured his PhD at Harvard University. After that, he worked as a Unitarian minister. Rattray was to teach Latin and English. He recruited others including Miss Measham to teach Botany, Miss Sarson to teach geography, and Miss Chapuzet to teach French. In all, 14 people started at the university when it opened its doors in October 1921: the principal, the secretary, 3 lecturers and nine students (eight women and one man). Two types of students were expected, around 100–150 teachers in training, and undergraduates hoping to sit the external degrees of London University. A students union was formed in 1923–24 with a Miss Bonsor as its first president.

In 1927, after it became University College, Leicester, students sat for the examinations for external degrees of the University of London. Two years later, it merged with the Vaughan Working Men’s College, which had been providing adult education in Leicester since 1862. In 1931, Dr Rattray resigned as principal. He was replaced in 1932 by Frederick Attenborough, who was the father of David and Richard Attenborough. He was succeeded by Charles Wilson in 1952.

In 1957, the University College was granted its Royal Charter, and has since then had the status of a university with the right to award its own degrees. The Percy Gee Student Union building was opened by Queen Elizabeth II on 9 May 1958.

Leicester University won the first ever series of University Challenge, in 1963. The university’s motto Ut Vitam Habeant –”so that they may have life”, is a reflection of the war memorial origins of its formation. It is believed to have been Rattray’s suggestion.

The university medical school, Leicester Medical School, opened in 1971.

In 1994, the University of Leicester celebrated winning the Queen’s Anniversary Prize for its work in Physics & Astronomy. The prize citation reads: “World-class teaching, research and consultancy programme in astronomy and space and planetary science fields. Practical results from advanced thinking”.

In 2011, the university was selected as one of four sites for national high performance computing (HPC) facilities for theoretical astrophysics and particle physics. An investment of £12.32 million, from the Government’s Large Facilities Capital Fund, together with investment from The Science and Technology Facilities Council (UK) and from universities contribute to a national supercomputer.

In September 2012, a ULAS team exhumed the body of King Richard III, discovering it in the former Greyfriars Friary Church in the city of Leicester. As a result of that success Prof King was asked to investigate whether a skeleton found in Jamestown was that of George Yeardley, the 1st colonial governor of Virginia and founder of the Virginia General Assembly.

In January 2017, Physics students from the University of Leicester made national news when they revealed their predictions on how long it would take a zombie apocalypse to wipe out humanity. They calculated that it would take just 100 days for zombies to completely take over earth. At the end of the 100 days, the students predicted that just 300 humans would remain alive and without infection.

In January 2021, around 200 UCU members at the university passed a no-confidence motion in Vice Chancellor Nishan Canagarajah because of proposed cuts putting 145 staff members at risk of redundancy. There was anger at his claim that redundancies are needed to “continue to deliver excellence”. In April, the UCU urged academics to boycott the university due to the planned redundancies, including encouraging people to not apply for jobs at Leicester or collaborate on new research projects.

In recent years, the university has disposed of some of its poorer quality property in order to invest in new facilities, and is currently undergoing a £300+ million redevelopment. The new John Foster Hall of Residence opened in October 2006. The David Wilson Library, twice the size of the previous University Library, opened on 1 April 2008 and a new biomedical research building (the Henry Wellcome Building) has already been constructed. A complete revamp of the Percy Gee Student Union building was completed in September 2010, and another is underway, due for completion in spring 2020. Nixon Court was extended and refurbished in 2011.

Organization

The university’s academic schools and departments are organized into colleges. In August 2015, the colleges were further restructured with the merging of Social Sciences and Arts, Humanities and Law to give the following structure:

College of Life Sciences

The college has the following academic schools:

Leicester Medical School

School of Biological Sciences

School of Psychology

School of Allied Health Professions

The research departments and institutes:

Cardiovascular Sciences

Genetics and Genome Biology (including the Leicester Cancer Research Centre)

Health Sciences (including the Leicester Diabetes Centre)

Infection, Immunity and Inflammation

Molecular and Cell Biology

Neuroscience, Psychology and Behaviour (including the Centre for Systems Neuroscience)

Leicester Precision Medicine Institute (including Leicester Drug Discovery and Diagnostics)

Leicester Institute of Structural and Chemical Biology

Leicester Medical School

The university is home to a large medical school, Leicester Medical School, which opened in 1971. The school was formerly in partnership with The University of Warwick (UK), and the Leicester-Warwick medical school proved to be a success in helping Leicester expand, and Warwick establish. The partnership ran the end of its course towards the end of 2006 and the medical schools became autonomous institutions within their respective universities.

College of Science and Engineering

The college comprises the following departments:

Chemistry

Informatics

School of Geography Geology & the Environment

Engineering

Mathematics

Physics and Astronomy

There are also interdisciplinary research centres for Space Research, Climate Change Research, Mathematical/Computational Modelling and Advanced Microscopy.

Engineering

The department offers MEng and BEng degrees in Aerospace Engineering, Embedded Systems Engineering, Communications and Electronic Engineering, Electrical and Electronic Engineering, Mechanical Engineering and General Engineering. Each course is accredited by the relevant professional institutions. The department also offers MSc courses.

Physics and Astronomy

The department has around 350 undergraduate students, following either BSc (three-year) or MPhys (four-year) degree courses, and over 70 postgraduate students registered for a higher degree.

The main Physics building accommodates several research groups—Radio and Space Plasma Physics (RSPP), X-ray and Observational Astronomy (XROA), and Theoretical Astrophysics (TA)—as well as centres for supercomputing, microscopy, Gamma and X-ray astronomy, and radar sounding, and the Swift UK Data Centre. A purpose-built Space Research Centre houses the Space Science and Instrumentation (SSI) group and provides laboratories, clean rooms and other facilities for instrumentation research, Earth Observation Science (EOS) and the Bio-imaging Unit. The department also runs the University of Leicester Observatory in Manor Road, Oadby, with a 20-inch telescope it is one of the UK’s largest and most advanced astronomical teaching facilities. The department has close involvement with the National Space Centre also located in Leicester.

The department is home to the university’s ALICE 3400+ core supercomputer and is a member of the UK’s DiRAC (DiStributed Research utilising Advanced Computing) consortium. DiRAC is the integrated supercomputing facility for theoretical modelling and HPC-based research in particle physics, astronomy and cosmology.

College of Social Sciences, Arts and Humanities

The college has 10 schools including:

American Studies

Archaeology and Ancient History

School of Arts

School of Business

Criminology

Education

History, Politics and International Relations

Leicester Law School

School of Media, Communication and Sociology

Museum Studies

Archaeology and Ancient History

The School of Archaeology and Ancient History was formed in 1990 from the then Departments of Archaeology and Classics, under the headship of Graeme Barker. The academic staff currently (as of January 2017) include 21 archaeologists and 8 ancient historians, though several staff teach and research in both disciplines.

The School has particular strengths in Mediterranean archaeology, ancient Greek and Roman history, and the archaeology of recent periods; and is also home to the University of Leicester Archaeological Services (ULAS).

Business

The Ken Edwards Building, formerly where the School of Management was based, is now part of the School of Business.

The School of Business was founded in 2016, bringing together the expertise of the School of Management and the Department of Economics. The new school now has approximately 150 academic staff, 50 from Economics and 100 from Management. In 2010 the former School of Management was ranked 2nd after Oxford University by the Guardian.

The School of Business provides postgraduate and undergraduate programmes in Management, Accounting and Economics. The School of Business, is one of the approximately 270 Schools/Universities in the world accredited by AMBA.

English

The School of English teaches English at degree level. The school offers English studies from contemporary writing to Old English and language studies. It contains the Victorian Studies Centre, the first of its kind in the UK. Malcolm Bradbury is one of the department’s most famous alumni: he graduated with a First in English in 1953.

Historical Studies

The School of Historical Studies is one of the largest of any university in the country. It has made considerable scholarly achievements in many areas of history, notably urban history, English local history, American studies and Holocaust studies. The school houses both the East Midlands Oral History Archive (EMOHA) and the Media Archive for Central England.

Law

The School of Law is one of the biggest departments in the university. According to The Times Online Good University Guide, the Faculty of Law was ranked very highly, making it one of the top law schools in the country.

Research

The university has research groups in the areas of astrophysics, biochemistry and genetics. The techniques used in genetic fingerprinting were invented and developed at Leicester in 1984 by Sir Alec Jeffreys. It also houses Europe’s biggest academic centre for space research, in which space probes have been built, most notably the Mars Lander Beagle 2, which was built in collaboration with The Open University (UK).

Leicester Physicists (led by Ken Pounds) were critical in demonstrating a fundamental prediction of Albert Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity – that black holes exist and are common in the universe. It is a founding partner of the £52 million National Space Centre.

Leicester is one of a small number of universities to have won the prestigious Queen’s Anniversary Prize for Higher Education on more than one occasion: in 1994 for physics & astronomy and again in 2002 for genetics.

The 2014 Research Excellence Framework (REF) exercise for the School of Archaeology and Ancient History, 74% of research activity, including 100% of its Research Environment, was classed as “world-leading” or “internationally excellent”, ranking it 6th among UK university departments teaching archaeology and 1st for the public impact of its research.

The Institute of Learning Innovation within the University of Leicester is a research and postgraduate teaching group. The institute has and continues to research on UK- and European-funded projects (over 30 as of August 2013), focusing on topics such as educational use of podcasting, e-readers in distance education, virtual worlds, open educational resources and open education, and learning design.

The university of Leicester has ranked very highly in Reuters top 100 of Europe’s most innovative universities. University of Leicester excelled in molecular and cell biology.

Leicester has been ranked as one of the top performing universities in the UK for COVID-19 research, after being awarded more than £10.8 million of government funding since the pandemic began. The University now sits alongside The University of Oxfordand University College London and has been recognized globally for its work, including being the first in the world to discover the link between people from black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) backgrounds being more susceptible to severe cases of coronavirus.

The university has been consistently ranked among the top 20 universities in the United Kingdom by the Times Good University Guide and The Guardian.

The university has ranked very high in The Sunday Times Good University Guide.