At

1.29.24

Katherine Kornei

The stratovolcano in central Mexico presents a rich case study of risk perception, science communication, and preparedness surrounding natural hazards.

Volcano Popocatépetl, north side, view from Paso de Cortez.

9 June 2006

Author Jakub Hejtmánek

If headlines are to be believed, the 22 million people living in the greater metropolitan area of Mexico City are in danger. The menace is Popocatépetl, a volcano that rumbled to life in 1994 after decades of quiescence. Reports frequently use words and phrases such as “threatening” and “booming eruptions” to describe the active stratovolcano 70 kilometers southeast of Mexico’s capital.

The real story is much more nuanced, of course—Popocatépetl poses varying levels of hazards, and people’s views about volcanic activity are framed by their life experiences and shaped by their own perceptions of risk as well as the communication efforts of scientists and governmental officials.

Popocatépetl is, perhaps, the best-known feature of the Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt, which extends more than 600 kilometers across central Mexico. The 5,400-meter-high stratovolcano can be seen from several cities and towns, and it features prominently in Aztec legends as well as the religious beliefs of many contemporary Mexicans, particularly those living in rural communities. Since the mid-1990s, Popocatépetl has become more active and has therefore been a fixture in the news and on social media.

“It’s one of the most active volcanoes in Mexico,” said Lizeth Caballero García, a volcanologist at the National Autonomous University of Mexico in Mexico City. “It’s considered the riskiest.”

Active Across the Ages

Popocatépetl has a long history of activity: A research team led by Ivan Sunyé Puchol recently estimated that the volcano has erupted explosively more than 25 times over the past 500,000 years. Sunyé Puchol, a geologist at the University of Rome, and his collaborators reconstructed the past activity of Popocatépetl and other volcanoes by age dating layers of pumice, a porous rock born from volcanic eruptions. The Popocatépetl pumice that Sunyé Puchol and his colleagues studied was birthed in sizeable eruptions, events with a volcanic explosivity index (VEI) in the range of 4–6, the team suggests. (For comparison, the 18 May 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens in Washington State was characterized by a VEI of 5.)

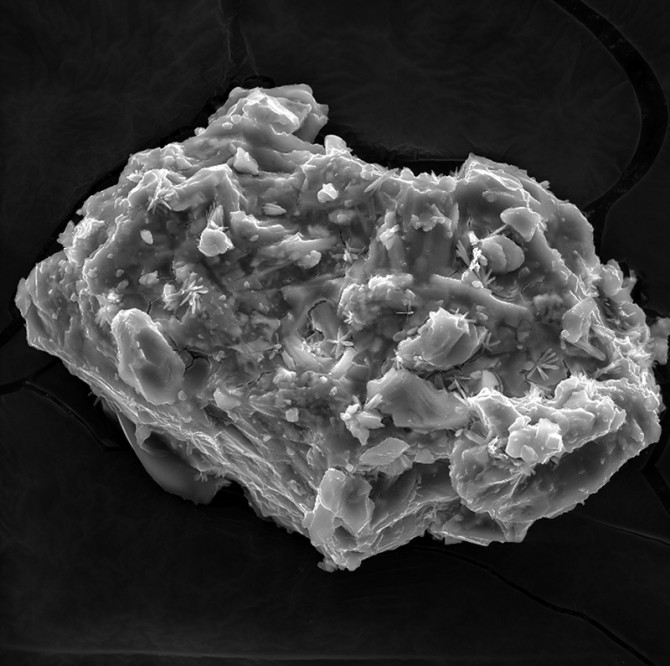

Popocatépetl’s last explosive eruption of significant size occurred roughly 1,100 years ago. However, the volcano rumbled to life again in late 1994 with a series of small eruptions (maximum VEI of 2) that produced a 7-kilometer-high column of ash. Popocatépetl has remained active since then, and light brown ash has repeatedly dusted nearby towns like Tetela del Volcán and even more outlying cities like Puebla and Mexico City. Mudflows of pumice and ash known as lahars have coursed down the volcano’s nearly vertical slopes. Pyroclastic density currents, clouds of hot gas and volcanic debris that race downslope at hundreds of kilometers per hour, have also been reported at Popocatépetl.

“Ash falls, lahars, and pyroclastic density currents are, in my opinion, the real hazards today,” said Sunyé Puchol.

The Cloud and the Governor

But accurately and effectively communicating the various risks posed by Popocatépetl is challenging work. For example, a phenomenon that outwardly appears to be dangerous—an ash cloud towering high in the atmosphere, for instance—might, in fact, pose little risk to nearby populations.

Ana Lillian Martin del Pozzo, a volcanologist at the National Autonomous University of Mexico, remembers a government official calling her late one night to ask for advice. The state governor was worried because he had seen a big, black cloud in the sky, and he was considering issuing an evacuation order. That’s just ash, Martin del Pozzo assured him, and it wasn’t cause for evacuation. But if that ash starts falling to the ground, she added, residents should take precautions like staying indoors whenever possible and covering their faces when going outside.

Advice like that makes sense to most people, said Martin del Pozzo, because the public generally has a good understanding that inhaling particulate matter can be harmful to the respiratory system (never mind that volcanic ash bears no resemblance to the ash produced by a fire).

However, there’s another deleterious effect of ash exposure that’s much less well-known, she said: “It’s on the eyes.” Volcanic ash, which is composed of bits of glass and rock, can literally abrade the delicate tissues of the ocular system. Symptoms such as redness, itching, and discharge are common, researchers found when they studied people living near an active volcano in Japan. People who live in the shadow of Popocatépetl should take a few simple steps to protect their eyes when ash is falling, said Martin del Pozzo. “Wear glasses. Wear a hat.”

The Shadow of Don Goyo

Not everyone heeds those warnings, however. When Caballero García visited Hueyapan, a small town in the state of Morelos, she heard stories of local women purposely going outside when ash was falling. They knew that the material came from Popocatépetl, a mountain they viewed as being imbued with spiritual power, and were trying to collect ash on their heads, said Caballero García. The women were mainly driven by curiosity, she said, but it’s important to remember that to many Mexicans, Popocatépetl is more than just a volcano.

“Popocatépetl is considered in some towns to be a sacred mountain, with a complex identity between God and human,” Caballero García said.

Popocatépetl appears in Aztec legends, and small towns near the volcano typically feature murals showing Popocatépetl in two forms: the volcanic edifice and an Aztec warrior known as “Don Goyo,” a generally benevolent personification of the volcano associated with Saint Gregory. Either way, “Popo has a human name,” said Caballero García. Every year on 12 March, the birthday of Don Goyo, people hike up the volcano’s flanks to leave offerings of food and flowers.

That duality—Popocatépetl the physical volcano and its spiritual likeness—affects how people conceptualize volcanic risk, which is itself shaped by life experiences and personal beliefs, among other factors.

Between 2013 and 2016, a team of researchers interviewed more than 130 residents of Tetela del Volcán, a town located just 15 kilometers from Popocatépetl’s crater, to better understand local risk perception surrounding Popocatépetl. Some of the participants were young enough that they had grown up knowing the volcano only in its more active phase; others remembered an earlier time when Popocatépetl was dormant.

The researchers found that older adults tended to harbor more symbolic beliefs about Popocatépetl and its personified form of Don Goyo. “The elderly have more conceptions of respect and symbolism with respect to the volcano,” said Esperanza López-Vázquez, a social and environmental psychologist at the Autonomous University of the State of Morelos in Cuernavaca, Mexico, and a member of the research team. Those beliefs correlated with lower perceptions of risk, the team found.

On the other hand, the research revealed that middle-aged adults and adolescents tended to base their impressions of Popocatépetl-related risks more on scientific information. Accordingly, younger people had a greater perception of risk, said López-Vázquez, despite learning about Popocatépetl from the oral histories of their elders. These differences in perceived risk, she said, can “generate tensions between generations.”

Both middle-aged adults and older adults remembered being urged to evacuate Tetela del Volcán in 2000 and 2001 because of increased volcanic activity. Poor road conditions made mass evacuations difficult, residents recalled, and there were underlying feelings of unease and distrust about leaving belongings and farm animals behind. It’s natural to assume that those life experiences would affect someone’s decision to evacuate again in the future, researchers concluded.

Young people had never experienced a Popocatépetl-related evacuation but had grown up accustomed to hearing and feeling the volcano’s rumblings, the team reported. “At the same time you are afraid, but it is something normal, which we are used to,” one young participant said.

Balancing Safety and Personal Beliefs

The residents of Tetela del Volcán clearly differ in their levels of volcanic risk perception, and they employ a wide range of strategies to cope with the presence of an active volcano. Those strategies include everything from personifying the volcano as a benevolent being, to believing that a dearth of recent disasters confers immunity from future hazards, to developing a strong community identity that views relocation as an act of abandonment.

“People have learned to live with the risk of the volcano,” said López-Vázquez.

In light of those varied coping strategies, scientists and policymakers have found it can be difficult to balance the need for public safety and respect for personal beliefs. Mexican officials have tended to err on the side of providing recommendations to avoid particularly risky areas rather than banning access to Popocatépetl entirely, for instance. (People are legally prevented from living within 12 kilometers of the volcano, however).

Helping people feel empowered is an important aspect of disaster preparedness. From ShakeAlert messages that provide warnings to drop and cover before an impending an earthquake to signs posted in coastal areas indicating tsunami evacuation routes, providing information in advance allows people to prepare and therefore feel more capable and confident when a disaster does strike.

In 1997, Mexico’s National Center for Disaster Prevention (CENAPRED) unveiled the first version of a hazards map for Popocatépetl. That map, which was updated again in 2016, indicates regions most likely to be affected by ashfall, lahars, pyroclastic density currents, and lava flows, among other volcanic risks.

The Popocatépetl hazards map is published online in both Spanish and Nahuatl, and it’s regularly publicized via social media, Tomás Alberto Sánchez Pérez, CENAPRED’s director of Communications, told Eos.

But just because a resource is online doesn’t mean that everyone is seeing it, of course. That’s particularly true because Internet access isn’t a given across all of Mexico. Urban centers like Puebla and Mexico City have plenty of connectivity, but many small communities aren’t as digitally equipped, said Sunyé Puchol, who lived near Mexico City from 2012 to 2018. “There are two worlds in Mexico,” he said.

The digital divide between urban and rural populations means that scientists and government officials alike must rely on multiple methods for communicating volcanic risks. The most tried and true, not surprisingly, involve making face-to-face connections.

Connecting in Person

Martin del Pozzo and her collaborators often bring physical copies of the Popocatépetl hazards map into schools and universities. “We’ve been doing that kind of in-person outreach for decades,” she said. “We began working with the people before Popo started erupting.” Martin del Pozzo has watched students grow up, and she’s developed a rapport with educators who invite her back year after year. “We’ve constructed this joint relationship,” she said.

Sunyé Puchol and other researchers have also visited numerous communities near Popocatépetl. In the wake of a magnitude 7.1 earthquake that struck central Mexico in 2017, Sunyé Puchol and other volunteers traveled to several small towns to provide relief supplies and talk with community members about the risks posed by natural hazards like earthquakes and volcanic activity. The earthquake itself had killed hundreds of people, and the ground shaking had also triggered several lahars on Popocatépetl. Sunyé Puchol and his colleagues emphasized that sometimes an unrelated hazard—in this case, an earthquake—can affect volcanic risks.

A lot of highly technical scientific data—including measurements of ground deformation, volcanic tremors, and gas emissions, for example—go into predicting Popocatépetl’s risks. But most of those measurements won’t make much sense to the average person, said Sunyé Puchol. It’s critical to distill that information to concepts that are understandable to nonscientists, he stressed. “Science is not finished until you explain it to everyone.”

Red, Yellow, Green

With the goal of facilitating clear communication about Popocatépetl, in 1998 the Mexican National Civil Protection System unveiled an alert system modeled on the familiar colors of a traffic light. The lowest level of the Volcanic Traffic Light Alert System is green and corresponds to very little or no risk. The next level, yellow, indicates a state of alert, and it’s divided into three phases. The highest level, red, means that evacuation might be imminent. Since its inception, the Volcanic Traffic Light Alert System has mostly toggled between the second and third phases of the yellow level.

“We’re hardly ever in green,” said Martin del Pozzo.

The relative simplicity of such a system can be helpful for conveying risk quickly. Similar color-based systems are in widespread use (for indicating fire danger, for example). Such systems are effective at conveying risk quickly in an intuitive way, said Simon Carn, a volcanologist at Michigan Technological University in Houghton. “Most people use these kinds of systems in order to avoid being too quantitative.”

However, there is a downside to keeping the inner workings of the Volcanic Traffic Light Alert System hidden from public view. People were initially skeptical about why the levels of the alert system kept changing, said Martin del Pozzo. That was especially true for populations that lived farther away from the volcano and were therefore more isolated from its impacts. But those communities are not immune: Ash from Popocatépetl has fallen on relatively distant Mexico City more than 19 times since 1994, and schools and airports in the region have occasionally been shuttered in response, most recently in May 2023.

Between 2020 and 2021, Caballero García and Edwin Hazel López Ortíz, an Earth scientist also at the National Autonomous University of Mexico, surveyed more than 4,800 people living in Mexico City. Caballero García and López Ortíz queried the respondents, who ranged in age from 12 to 99, about their scientific understanding of volcanic ash, their recollection of prior Popocatépetl ashfall events, their awareness of measures to protect themselves from falling ash, and their feelings surrounding an ashfall event.

The team noted that although most people knew what volcanic ash was and how it was produced, they were largely unaware of how to protect themselves from it. For example, nearly 90% of people aged 12–24 did not know what to do in the event of ashfall, Caballero García and López Ortíz found. Because younger people tended to seek out news about Popocatépetl predominantly from social media, the team emphasized the importance of sharing protective measures related to ashfall on social media platforms.

Experiencing an ashfall event furthermore triggered a wide range of emotional responses, Caballero García and López Ortíz found. Respondents commonly reported feelings of peril, indifference, interest, fear, and surprise. For participants old enough to have experienced an ashfall event in the past, a fresh dusting of ash was also an opportunity for a teaching moment. It allowed people who are parents, said Caballero García, to tell their children about Popocatépetl and how to remain safe.

Not surprisingly, the researchers found that individuals who remembered an ashfall event were more likely to believe that ash could once again blanket their home or place of work. People who were aware of Popocatépetl’s hazards map were more likely to feel prepared in the event of falling ash, Caballero García and López Ortíz reported at AGU’s Fall Meeting 2021.

Never Deny

Like other natural hazards, volcanoes clearly manifest their risks in complicated ways. “We can’t predict eruptions very accurately,” said Carn. Moreover, he continued, events like falling ash can be affected by other phenomena that are themselves unpredictable. For instance, “ashfall depends on where the wind is blowing,” he said. “That adds further uncertainty.”

In the face of all that ambiguity, what’s a person to do? López-Vázquez maintained that no one particular mindset is healthiest when it comes to internalizing volcanic risks. Instead, she said, the key is acknowledging that there is always some level of risk associated with living near a volcano like Popocatépetl. “The most important thing is not to deny that it exists.”

See the full article here .

Comments are invited and will be appreciated, especially if the reader finds any errors which I can correct. Use “Reply” at the bottom of the post.

five-ways-keep-your-child-safe-school-shootings

Please help promote STEM in your local schools.

“Eos” is the leading source for trustworthy news and perspectives about the Earth and space sciences and their impact. Its namesake is Eos, the Greek goddess of the dawn, who represents the light shed on understanding our planet and its environment in space by the Earth and space sciences.