From The Arizona State University (US)

via

September 14, 2021

Paul Scott Anderson

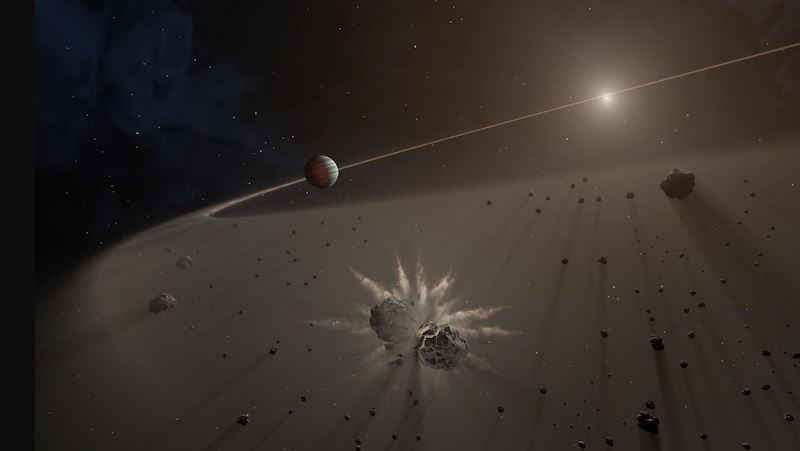

Artist’s concept of planet-forming collisions in the early solar system. Where is this debris today? Hint: It’s not in the asteroid belt. Image via NASA/ JPL-Caltech (US)/ ASU.

The case of the missing impact debris

Billions of years ago, the early solar system was a chaotic and violent place. Solid objects called planetesimals had condensed from the primordial cloud that gave birth to our solar system. And the planetesimals frequently collided, and at times stuck together. The process formed larger and larger objects, leading to bigger and bigger collisions. Over eons of time, this process built the major planets, like Earth. So, today, we’d expect to glimpse some of the debris from these early planet-forming collisions. We’d expect to find it orbiting our sun, in the asteroid belt in particular. But why don’t we? New computer simulations by Arizona astronomers offer a solution to the missing impact debris problem. They suggest that, instead of creating rocky debris, large collisions in the early solar system caused solid rocky bodies to vaporize into gas. And, the astronomers said:

“Unlike solid and molten debris, this gas more easily escapes the solar system, leaving little trace of these planet-smashing events.”

The researchers published their peer-reviewed results in The Astrophysical Journal Letters on July 13, 2021.

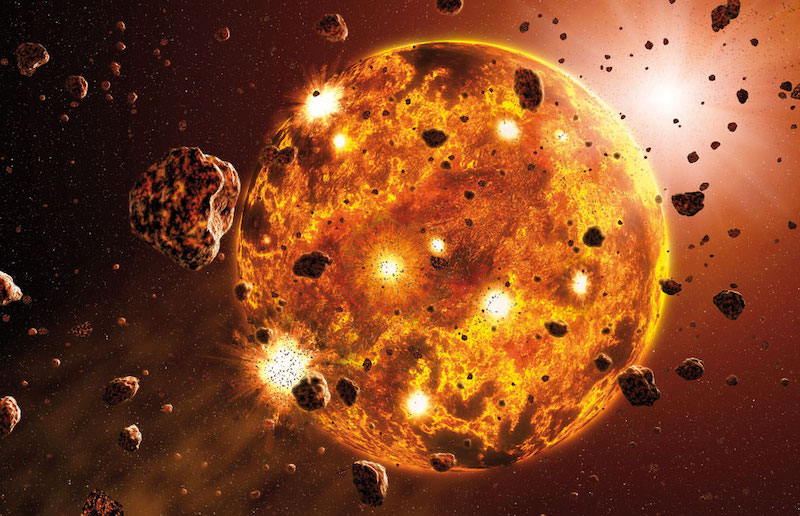

Artist’s concept of small planetesimals colliding in the early solar system to form a larger planet. Image via Alan Brandon/ Nature/ Planet Hunters.

Simulating the early solar system

Travis Gabriel and Harrison Allen-Sutter, both at Arizona State University, led the new research. While previous studies by other scientists mostly focused on the effects of these early impacts, these scientists took a different approach. As Allen-Sutter explained:

“Most researchers focus on the direct effects of impacts, but the nature of the debris has been underexplored.”

And Gabriel added:

“It has long since been understood that numerous large collisions are required to form Mercury, Venus, Earth, the moon and perhaps Mars. But the tremendous amount of impact debris expected from this process is not observed in the asteroid belt, so it has always been a paradoxical situation.”

Scientists refer to the mystery of the apparently missing impact debris as the “Missing Mantle Paradox” (mantle, in this case, doesn’t refer to Earth’s mantle). Or they call it the “Great Dunite Shortage”. Dunite is a kind of rock, consisting largely of olivine, and it’s olivine that’s at the heart of this mystery.

Formation of the moon

The results also have implications for the formation of Earth’s own moon. According to current understanding, the moon was formed from a collision between a Mars-sized body and the early Earth. That collision also released debris into the solar system. According to Gabriel:

“After forming from debris bound to the Earth, the moon would have also been bombarded by the ejected material that orbits the sun over the first hundred million years or so of the moon’s existence. If this debris was solid, it could compromise or strongly influence the moon’s early formation, especially if the collision was violent.

If the material was in gas form, however, the debris may not have influenced the early moon at all.”

Scientists think that our own moon formed from a collision between the early Earth and another rocky body about the size of Mars. Image via Hagai Perets/ Smithsonian Magazine.

Impact debris around other stars

Also, since our solar system is thought to have formed in a similar way to planetary systems around other stars, the study results could provide clues about impact debris elsewhere. Gabriel commented on this, saying:

“There is growing evidence that certain telescope observations may have directly imaged giant impact debris around other stars. Since we cannot go back in time to observe the collisions in our solar system, these astrophysical observations of other worlds are a natural laboratory for us to test and explore our theory.”

In 2019, astronomers also found evidence of a planetary collision in a solar system 300 light-years away. That impact is estimated to have occurred sometime within only the past 1,000 years, showing that such events still happen, even between planets.

It would seem then that the mystery of the missing impact debris may have been solved. As science marches on – and if the new simulations hold solid – they will provide valuable clues about how our solar system formed billions of years ago. And they’ll also offer a glimpse into planet-forming processes in other solar systems.

See the full article here .

five-ways-keep-your-child-safe-school-shootings

Please help promote STEM in your local schools.

The Arizona State University (US) is a public research university in the Phoenix metropolitan area. Founded in 1885 by the 13th Arizona Territorial Legislature, ASU is one of the largest public universities by enrollment in the U.S.

One of three universities governed by the Arizona Board of Regents, ASU is a member of the Universities Research Association (US) and classified among “R1: Doctoral Universities – Very High Research Activity.” ASU has nearly 150,000 students attending classes, with more than 38,000 students attending online, and 90,000 undergraduates and more nearly 20,000 postgraduates across its five campuses and four regional learning centers throughout Arizona. ASU offers 350 degree options from its 17 colleges and more than 170 cross-discipline centers and institutes for undergraduates students, as well as more than 400 graduate degree and certificate programs. The Arizona State Sun Devils compete in 26 varsity-level sports in the NCAA Division I Pac-12 Conference and is home to over 1,100 registered student organizations.

ASU’s charter, approved by the board of regents in 2014, is based on the New American University model created by ASU President Michael M. Crow upon his appointment as the institution’s 16th president in 2002. It defines ASU as “a comprehensive public research university, measured not by whom it excludes, but rather by whom it includes and how they succeed; advancing research and discovery of public value; and assuming fundamental responsibility for the economic, social, cultural and overall health of the communities it serves.” The model is widely credited with boosting ASU’s acceptance rate and increasing class size.

The university’s faculty of more than 4,700 scholars has included 5 Nobel laureates, 6 Pulitzer Prize winners, 4 MacArthur Fellows, and 19 National Academy of Sciences members. Additionally, among the faculty are 180 Fulbright Program American Scholars, 72 National Endowment for the Humanities fellows, 38 American Council of Learned Societies fellows, 36 members of the Guggenheim Fellowship, 21 members of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, 3 members of National Academy of Inventors, 9 National Academy of Engineering members and 3 National Academy of Medicine members. The National Academies has bestowed “highly prestigious” recognition on 227 ASU faculty members.

History

Arizona State University was established as the Territorial Normal School at Tempe on March 12, 1885, when the 13th Arizona Territorial Legislature passed an act to create a normal school to train teachers for the Arizona Territory. The campus consisted of a single, four-room schoolhouse on a 20-acre plot largely donated by Tempe residents George and Martha Wilson. Classes began with 33 students on February 8, 1886. The curriculum evolved over the years and the name was changed several times; the institution was also known as Tempe Normal School of Arizona (1889–1903), Tempe Normal School (1903–1925), Tempe State Teachers College (1925–1929), Arizona State Teachers College (1929–1945), Arizona State College (1945–1958) and, by a 2–1 margin of the state’s voters, Arizona State University in 1958.

In 1923, the school stopped offering high school courses and added a high school diploma to the admissions requirements. In 1925, the school became the Tempe State Teachers College and offered four-year Bachelor of Education degrees as well as two-year teaching certificates. In 1929, the 9th Arizona State Legislature authorized Bachelor of Arts in Education degrees as well, and the school was renamed the Arizona State Teachers College. Under the 30-year tenure of president Arthur John Matthews (1900–1930), the school was given all-college student status. The first dormitories built in the state were constructed under his supervision in 1902. Of the 18 buildings constructed while Matthews was president, six are still in use. Matthews envisioned an “evergreen campus,” with many shrubs brought to the campus, and implemented the planting of 110 Mexican Fan Palms on what is now known as Palm Walk, a century-old landmark of the Tempe campus.

During the Great Depression, Ralph Waldo Swetman was hired to succeed President Matthews, coming to Arizona State Teachers College in 1930 from Humboldt State Teachers College where he had served as president. He served a three-year term, during which he focused on improving teacher-training programs. During his tenure, enrollment at the college doubled, topping the 1,000 mark for the first time. Matthews also conceived of a self-supported summer session at the school at Arizona State Teachers College, a first for the school.

1930–1989

In 1933, Grady Gammage, then president of Arizona State Teachers College at Flagstaff, became president of Arizona State Teachers College at Tempe, beginning a tenure that would last for nearly 28 years, second only to Swetman’s 30 years at the college’s helm. Like President Arthur John Matthews before him, Gammage oversaw the construction of several buildings on the Tempe campus. He also guided the development of the university’s graduate programs; the first Master of Arts in Education was awarded in 1938, the first Doctor of Education degree in 1954 and 10 non-teaching master’s degrees were approved by the Arizona Board of Regents in 1956. During his presidency, the school’s name was changed to Arizona State College in 1945, and finally to Arizona State University in 1958. At the time, two other names were considered: Tempe University and State University at Tempe. Among Gammage’s greatest achievements in Tempe was the Frank Lloyd Wright-designed construction of what is Grady Gammage Memorial Auditorium/ASU Gammage. One of the university’s hallmark buildings, ASU Gammage was completed in 1964, five years after the president’s (and Wright’s) death.

Gammage was succeeded by Harold D. Richardson, who had served the school earlier in a variety of roles beginning in 1939, including director of graduate studies, college registrar, dean of instruction, dean of the College of Education and academic vice president. Although filling the role of acting president of the university for just nine months (Dec. 1959 to Sept. 1960), Richardson laid the groundwork for the future recruitment and appointment of well-credentialed research science faculty.

By the 1960s, under G. Homer Durham, the university’s 11th president, ASU began to expand its curriculum by establishing several new colleges and, in 1961, the Arizona Board of Regents authorized doctoral degree programs in six fields, including Doctor of Philosophy. By the end of his nine-year tenure, ASU had more than doubled enrollment, reporting 23,000 in 1969.

The next three presidents—Harry K. Newburn (1969–71), John W. Schwada (1971–81) and J. Russell Nelson (1981–89), including and Interim President Richard Peck (1989), led the university to increased academic stature, the establishment of the ASU West campus in 1984 and its subsequent construction in 1986, a focus on computer-assisted learning and research, and rising enrollment.

1990–present

Under the leadership of Lattie F. Coor, president from 1990 to 2002, ASU grew through the creation of the Polytechnic campus and extended education sites. Increased commitment to diversity, quality in undergraduate education, research, and economic development occurred over his 12-year tenure. Part of Coor’s legacy to the university was a successful fundraising campaign: through private donations, more than $500 million was invested in areas that would significantly impact the future of ASU. Among the campaign’s achievements were the naming and endowing of Barrett, The Honors College, and the Herberger Institute for Design and the Arts; the creation of many new endowed faculty positions; and hundreds of new scholarships and fellowships.

In 2002, Michael M. Crow became the university’s 16th president. At his inauguration, he outlined his vision for transforming ASU into a “New American University”—one that would be open and inclusive, and set a goal for the university to meet Association of American Universities (US) criteria and to become a member. Crow initiated the idea of transforming ASU into “One university in many places”—a single institution comprising several campuses, sharing students, faculty, staff and accreditation. Subsequent reorganizations combined academic departments, consolidated colleges and schools, and reduced staff and administration as the university expanded its West and Polytechnic campuses. ASU’s Downtown Phoenix campus was also expanded, with several colleges and schools relocating there. The university established learning centers throughout the state, including the ASU Colleges at Lake Havasu City and programs in Thatcher, Yuma, and Tucson. Students at these centers can choose from several ASU degree and certificate programs.

During Crow’s tenure, and aided by hundreds of millions of dollars in donations, ASU began a years-long research facility capital building effort that led to the establishment of the Biodesign Institute at Arizona State University, the Julie Ann Wrigley Global Institute of Sustainability, and several large interdisciplinary research buildings. Along with the research facilities, the university faculty was expanded, including the addition of five Nobel Laureates. Since 2002, the university’s research expenditures have tripled and more than 1.5 million square feet of space has been added to the university’s research facilities.

The economic downturn that began in 2008 took a particularly hard toll on Arizona, resulting in large cuts to ASU’s budget. In response to these cuts, ASU capped enrollment, closed some four dozen academic programs, combined academic departments, consolidated colleges and schools, and reduced university faculty, staff and administrators; however, with an economic recovery underway in 2011, the university continued its campaign to expand the West and Polytechnic Campuses, and establish a low-cost, teaching-focused extension campus in Lake Havasu City.

As of 2011, an article in Slate reported that, “the bottom line looks good,” noting that:

“Since Crow’s arrival, ASU’s research funding has almost tripled to nearly $350 million. Degree production has increased by 45 percent. And thanks to an ambitious aid program, enrollment of students from Arizona families below poverty is up 647 percent.”

In 2015, the Thunderbird School of Global Management became the fifth ASU campus, as the Thunderbird School of Global Management at ASU. Partnerships for education and research with Mayo Clinic established collaborative degree programs in health care and law, and shared administrator positions, laboratories and classes at the Mayo Clinic Arizona campus.

The Beus Center for Law and Society, the new home of ASU’s Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law, opened in fall 2016 on the Downtown Phoenix campus, relocating faculty and students from the Tempe campus to the state capital.