By: The OpenZika research team

3 Oct 2017

Summary

The OpenZika researchers are continuing to screen millions of chemical compounds as they look for potential treatments for the Zika virus. In this update, they report on the second stage of the project, using a newly prepared, massive library of 30.2 million compounds that are being screened against the Zika virus proteins. They also continue to spread the word about the project.

Project Background

The Zika virus has “evolved” from a global health emergency to a long-term threat. Scientists throughout the world continue to study the virus and search for ways to stem its spread, including potential vaccines and means of controlling the mosquito population, as well as looking for treatments. As of this update, there is still no vaccine for the Zika virus, and no cure.

We remain convinced that the search for effective treatments is crucial to stemming the tide of the virus. In addition to the OpenZika project, several other labs are doing cell-based screens with drugs already approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Still, few to none of the compounds that have been identified thus far are both potent enough against Zika virus and also safe for pregnant women.

Continuing progress on choosing compounds for lab testing

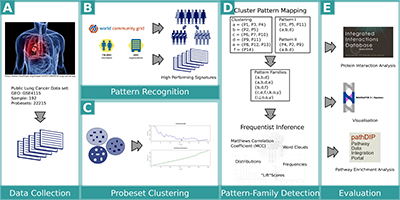

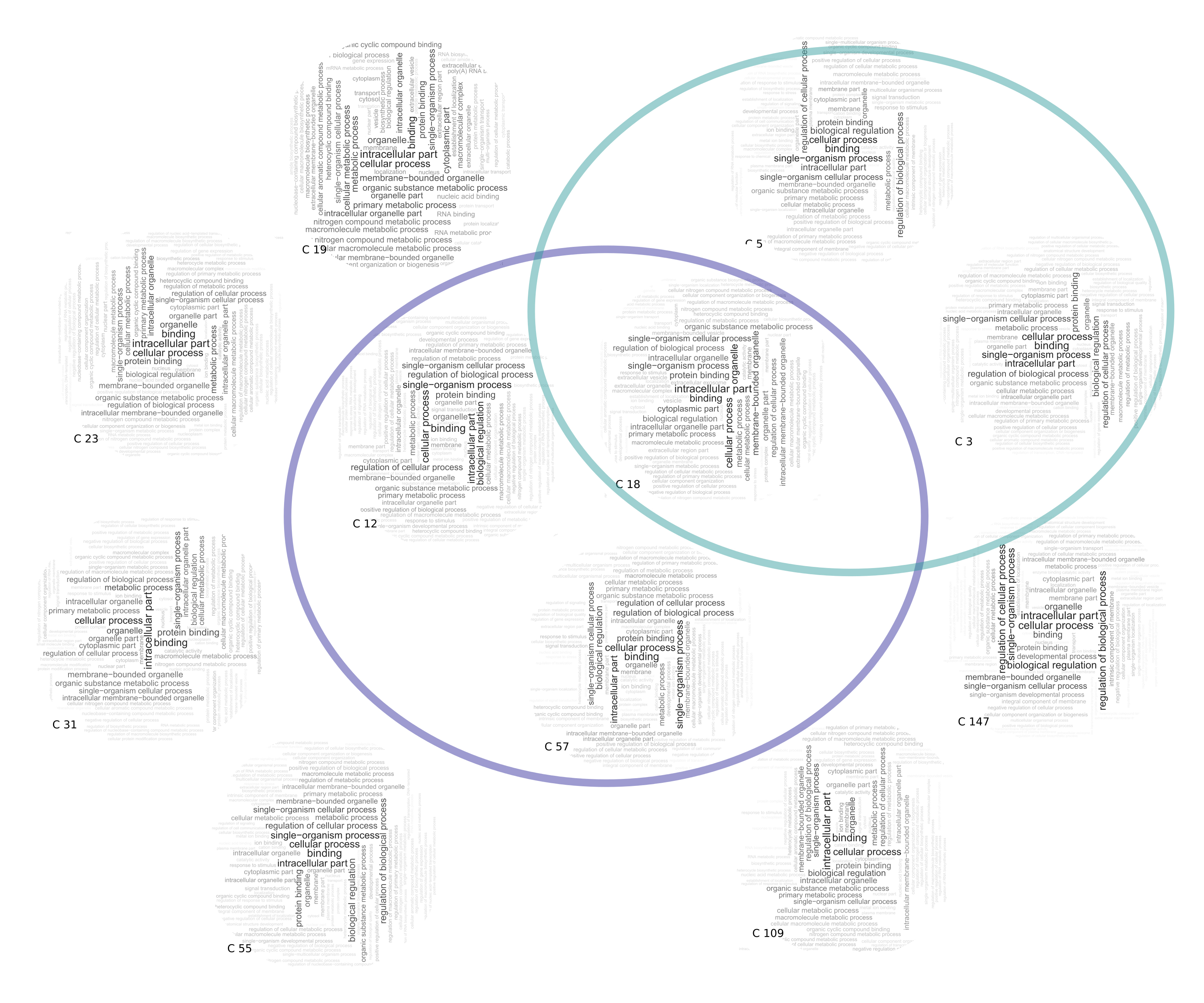

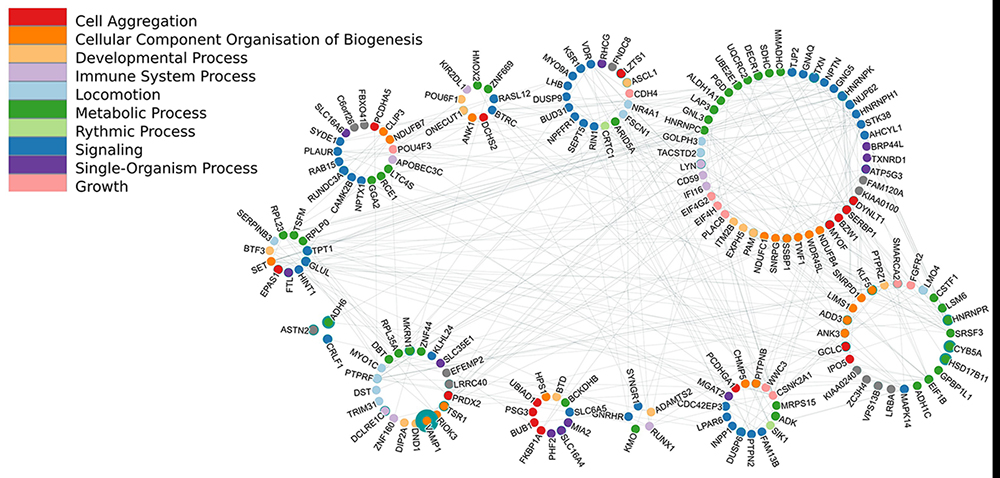

We are continuing the analysis phase of the project, focusing on the results against the new target structures solved for NS3 helicase, NS5 polymerase, NS2B-NS3 protease, and NS1 glycoprotein.

o select the NS3 helicase candidates, we have been using distinct approaches for filtering and analyzing the virtual screening results. The first one is target specific, based on molecular docking calculations. Since there are two crystal derived structures of helicase (with and without RNA-bound) in the PDB (Protein Data Bank, a database that stores and freely distributes atomic-resolution structures of biological macromolecules), we docked approximately 7,600 compounds in a composite library composed of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration-approved drugs, the drugs approved in the European Union, and the U.S. National Institutes of Health clinical collection against both of these structures of NS3 helicase. The docking results were then filtered by the estimated binding free energy (the docking score) and by the minimum number of hydrogen bonds that were predicted to form with the helicase target, followed by visual inspection of the predicted binding modes.

Subsequently, in a second workflow the candidates passed through developed and validated QSAR models (Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship), which are based on phenotypic data (cell-based assay results) on the Zika virus available in the PubChem Bioassay Database (AID1224857).

After visually inspecting the structures of the compounds to detect medicinal chemistry related liabilities, we selected 9 candidates and ordered them. They are currently being assayed by our collaborator at the University of California, San Diego, in Dr. Jair L. Siqueira-Neto’s lab.

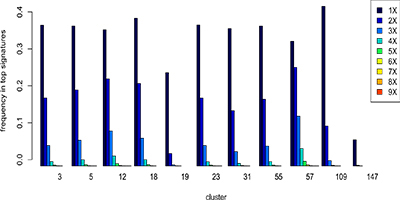

Workflow 1: 232 compounds passed a collection of different energetic and interaction-based docking filters, and their predicted binding modes were visually inspected by Dr. Alexander L. Perryman, to select the candidate compounds that were discussed in our previous project update. These candidates are currently being assayed by Professor Shan-Lu Liu’s lab at The Ohio State University.

Workflow 2: These 232 compounds were then scored with the consensus QSAR model (trained with cell-based Zika assay data), and 74 compounds passed this additional filter. The docked binding modes of these 74 compounds were inspected in detail by Dr. Melina Mottin and Dr. Carolina Horta Andrade.

Of the compounds that passed the inspection of their docked modes, 9 passed subsequent medicinal chemistry-based inspection (by Dr. Sean Ekins and Professor Joel Freundlich), were ordered, and are currently being assayed by Dr. Siqueira-Neto.

Status of the calculations

In total, we have submitted 3.5 billion docking jobs, which involved 427 different target sites. Our initial screens used an older library of 6 million commercially available compounds, and our current experiments utilize a newer library of 30.2 million compounds. We have already received approximately 2.6 billion of these results on our server (there is some lag time between when the calculations are performed on your volunteered machines and when we get the results, since all of the results per “package” of approximately 10,000 – 50,000 different docking jobs need to be returned to World Community Grid, re-organized, and then compressed before sending them to our server).

Thus far, the > 80,000 volunteers who have donated their spare computing power to OpenZika have given us > 34,000 CPU years worth of docking calculations, at a current average of 73 CPU years per day! Thank you all very much for your help!!

Except for a few stragglers, we have received all of the results for our experiments that involve docking 6 million compounds versus NS1, NS3 helicase (both the RNA binding site and the ATP site), and NS5 (both the RNA polymerase and the methyltransferase domains). We are currently receiving the results from our most recent experiments that screen 30.2 million compounds against the NS2B / NS3 protease.

A new stage of the project, and sharing the wealth

As described above, instead of docking 6 million compounds, we are now screening a new library of 30.2 million compounds against all the ZIKV targets. This new, massive library was originally obtained in a different type of format from the ZINC15 server. It represents almost all of “commercially available chemical space” (that is, almost all of the “small molecule” drug-like and hit-like compounds that can be purchased from reputable chemical vendors).

The ZINC15 server provided these files as “multi-molecule mol2” files (that is, up to 100,000 different compounds were contained in each “mol2” formatted file). These files had to be re-formatted (we used the Raccoon program from Dr. Stefano Forli, who is part of the FightAIDS@Home team) by splitting them into individual mol2 files (1 compound per file) and then converting them into the “pdbqt” docking input format.

We then ran a quick quality control test to make sure that the software used for the project, AutoDock Vina, could properly use each pdbqt file (a type of docking input file developed by Professor Art Olson’s lab) as an input.

Many compounds had to be rejected, because they had types of atoms that cause Vina to crash (such as silicon or boron atoms), and we obviously don’t want to waste the computer time that you donate by submitting calculations that will crash.

We then ran a quick quality control test to make sure that the software used for the project, AutoDock Vina, could properly use each pdbqt file (a type of docking input file developed by Professor Art Olson’s lab) as an input. Many compounds had to be rejected, because they had types of atoms that cause Vina to crash (such as silicon or boron atoms), and we obviously don’t want to waste the computer time that you donate by submitting calculations that will crash.

By splitting, reformatting, and testing hundreds of thousands of compounds per day, day after day, after approximately 6 months this massive new library of compounds was prepared and ready to be used in our OpenZika calculations. Without the tremendous resources that World Community Grid volunteers provide for this project, we would not even dream of trying to dock over 30 million compounds against many different targets from the Zika virus. Thank you all very much!!!

Soon after we started using this new massive library for our virtual screens in OpenZika, Viktors Berstis at IBM/World Community Grid put us in contact with Dr. Akira Nakagawara, the principal investigator of the Smash Childhood Cancer project. To help expand the scope of their experiments that search for new cancer drugs, we gave them a copy of our new library of 30.2 million compounds.

For more information about these experiments, please visit our website.

Publications and Collaborations

OpenZika project results were presented on July 7-14 at an International Conference, the 46th World Chemistry Congress, in Sao Paulo, Brazil, which had almost 3,000 attendees.

Dr. Melina Mottin presented a lecture entitled “OpenZika: Opening the Discovery of New Antiviral candidates against Zika Virus and Insights into Dynamic behavior of NS3 Helicase”

(Photos taken by Carolina Horta Andrade.)

We will be presenting a poster at Cell Symposia: Emerging and Re-emerging Viruses, on October 1-3, 2017, in Arlington, VA, U.S.A:

Title:

OpenZika: Opening up the discovery of new antiviral candidates against zika virus

Authors:

A.L. Perryman, M. Mottin, R.C. Braga, R.A. Da Silva, S. Ekins, C.H. Andrade

Presenting Author:

S. Ekins

Our PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases paper, “OpenZika: An IBM World Community Grid Project to Accelerate Zika Virus Drug Discovery,” was published on October 20 2016, and it has already been viewed over 4,700 times. Anyone can access and read this paper for free. Another research paper “Illustrating and homology modeling the proteins of the Zika virus” has been formally accepted by F1000Research and viewed > 4,200 times.

We have also recently published another research paper entitled Molecular Dynamics simulations of Zika Virus NS3 helicase: Insights into RNA binding site activity in a special issue on Flaviviruses for the journal Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. This study of the NS3 helicase system helped us learn more about this promising target for blocking Zika replication. The results will help guide how we analyze the virtual screens that we performed against NS3 helicase, and the Molecular Dynamics simulations generated new conformations of this system that we will use as targets in new virtual screens that we perform as part of OpenZika.

These articles are helping to bring additional attention to the project and to encourage the formation of new collaborations. For example, a group from Physics Institute at Sao Carlos, University of Sao Paulo, Brazil, coordinated by Professor Glaucius Oliva, contacted us because of our PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases paper to discuss a new collaboration to test the selected candidate compounds directly on enzymatic assays with Zika virus proteins. He is the principal investigator for a grant funded by CNPq and FAPESP (Brazilian funding agencies), aiming to clone, express, purify, solve the structure of all the Zika virus proteins, and to develop enzymatic assays to test and identify potential inhibitors. For now, they have already solved a high-resolution (1.9 Å; an Angstrom is a tenth of a nanometer) crystal structure of ZIKV NS5 RNA polymerase (5U04), which has been released on the PDB (Protein Data Bank), and they are working on the determination of new structures of NS3 helicase. We have just started this new collaboration, and the nine selected candidates described earlier in this update are currently being assayed by Prof. Glaucius Oliva and his team to see if they can bind to the NS3 helicase, using the differential scanning fluorescence (DSF) technique and/or if they can inhibit the ATPase activity of this protein.

There is additional news at the full article.

See the full article here.

Ways to access the blog:

https://sciencesprings.wordpress.com

http://facebook.com/sciencesprings

Please help promote STEM in your local schools.

![]()

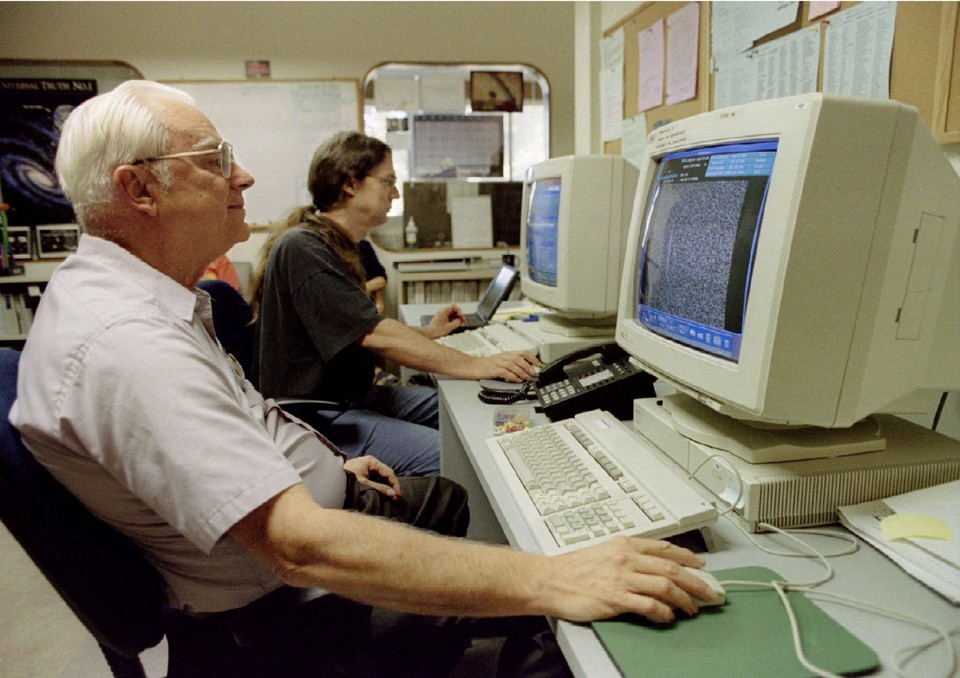

“World Community Grid (WCG) brings people together from across the globe to create the largest non-profit computing grid benefiting humanity. It does this by pooling surplus computer processing power. We believe that innovation combined with visionary scientific research and large-scale volunteerism can help make the planet smarter. Our success depends on like-minded individuals – like you.”

WCG projects run on BOINC software from UC Berkeley.

BOINC is a leader in the field(s) of Distributed Computing, Grid Computing and Citizen Cyberscience.BOINC is more properly the Berkeley Open Infrastructure for Network Computing.

CAN ONE PERSON MAKE A DIFFERENCE? YOU BET!!

My BOINC

“Download and install secure, free software that captures your computer’s spare power when it is on, but idle. You will then be a World Community Grid volunteer. It’s that simple!” You can download the software at either WCG or BOINC.

Please visit the project pages-

Smash Childhood Cancer

Help Stop TB

Outsmart Ebola together

Discovering Dengue Drugs – Together

World Community Grid is a social initiative of IBM Corporation

IBM Corporation