From The School of Engineering and Applied Science

At

And

At

The University of Wisconsin-Madison

6.14.24

Since it was developed a few decades ago, the chemical separation process of organic solvent nanofiltration (OSN), has drawn attention for its potential to revolutionize vital industries, including those in fuel, food, and pharmaceuticals.

Now, a team of researchers from Yale and the University of Wisconsin-Madison has upended the prevailing wisdom on how this rapidly emerging technology works – an insight that could significantly improve the technology. The results of their work are published in Science Advances.

Fig. 1. NEMD simulation of solvent transport through a PDMS membrane.

(A) Schematic of the molecular simulation box for solvent (acetone or methanol) transport through a PDMS membrane. The simulation box consists of the PDMS membrane (yellow) with a thickness of 10 nm, solvent molecules that are visualized as a light blue transparent surface, and two graphene sheets (orange) acting as rigid pistons. Hydrostatic pressure (P1) is applied to the graphene sheet on the feed side, and a standard atmospheric pressure (P2) is applied on the graphene sheet on the permeate side, resulting in a pressure difference ΔP = P1 − P2 during the simulation. The snapshot is captured at the beginning of the simulation, showing a majority of the solvent molecules located on the feed side. (B) Distribution of the percolated solvent-accessible free volume in the PDMS membrane after reaching a steady state under ΔP = 300 bar. The colors indicate the depth in the x direction: The color gradient transitioning from blue to red represents the position of free volume within the membrane, from the feed side to the permeate side. The size of each box is 10.0 nm by 4.81 nm by 4.81 nm (x by y by z). (C and D) Coordination number distribution of acetone and methanol molecules in the bulk feed, within the PDMS membrane, and in the permeate after achieving a steady state under ΔP = 300 bar. (E and F) Pressure distribution across the PDMS membrane for the acetone and methanol transport simulations under ΔP = 300 and 600 bar. The shaded areas represent the membrane.

See the science paper for further instructive material with images.

Organic solvents are liquids that contain carbon and oxygen – examples include alcohols, ethanol, benzene, and ketones. OSN uses membranes with nanosized holes to separate the chemicals. Applications include hydrocarbon separation in oil refining and purifying pharmaceutical ingredients. Because it’s much cheaper and doesn’t rely on chemical additives, it’s considered by many to be a potentially better alternative to such traditional technologies as distillation, evaporation, and solvent extraction.

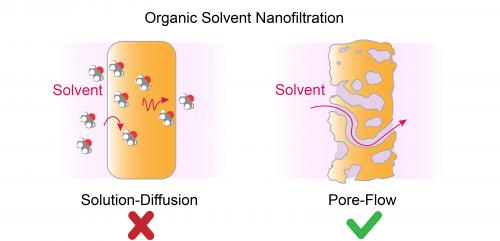

Exactly how it works, though, has been unclear. The most widely held theory posits that OSN relies on solution-diffusion mechanism – that is, a process in which solvent molecules dissolve and diffuse through the membrane from where they’re highly concentrated to wherever there are fewer molecules.

In a previous study [Science Advances], Yale’s Menachem Elimelech and the University of Wisconsin-Madison team used a combination of experiments and computer simulations to negate a decades-long theory on the physics of reverse osmosis, a method for removing salt from seawater.

As with OSN, the traditional view attributed reverse osmosis to the solution-diffusion mechanism. Elimelech’s research, though, demonstrated that it was actually changes in pressure within the membranes that pushed the water through the membranes, also known as the pore-flow model.

Since both processes have similarities, Elimelech and the research team applied their skepticism toward the conventional thinking on organic solvent nanofiltration. Using a similar set of experiments and computer simulations, Elimelech and his University of Wisconsin-Madison collaborators showed that the OSN process is driven not by the concentration of solvent molecules but – as in reverse osmosis – by changes in pressure.

One key piece of evidence, said Elimelech, is that the pores of the membranes for organic solvents are large enough to allow the passage of numerous solvent molecules that are held together.

“So it’s a cluster,” said Elimelech, the Sterling Professor of Chemical and Environmental Engineering. “And once you have a cluster solvent, it cannot move by diffusion. You need to have a driving force like pressure.”

They also found that for organic solvents, which are more complex than water, friction between the solvent and the polymer membrane plays a significant role. The researchers note that how strongly the solvent binds to the material is intricately linked to how fast the solvent flows through the membrane. In some cases, certain organic solvents can also stretch or compress the polymer material by interacting with it.

With a better understanding of the physics of OSN, scientists can improve the technology of OSN. For instance, Elimelech said, they can use these discoveries to optimize the design of the filtering membranes, thereby enabling a diverse range of separations and clean energy technologies.

Ying Li, an associate professor of mechanical engineering at UW-Madison who led the computer simulations, said that their investigations emphasize the “crucial role played by the disparity between solvent size and membrane pore size in dictating solvent permeance.”

“Fine-tuning the pore size of various dense polymer membranes to approximate the molecular size of unwanted permeants, coupled with the use of a solvent possessing a smaller molecular size, holds the potential for achieving highly selective separations in OSN,” Li said.

See the full article here .

Comments are invited and will be appreciated, especially if the reader finds any errors which I can correct.

five-ways-keep-your-child-safe-school-shootings

Please help promote STEM in your local schools.

The College of Engineering is a thriving, top-ranked college in Madison, Wisconsin—one of the most fantastic cities in the country. We think boldly and act confidently, not only as engineers, but as engaged citizens. As an engineering community, we value unique perspectives, we foster respect and inclusivity, and we work together to bring new ideas to life. Building on a heritage of impact, we develop the leaders, knowledge and technologies that improve lives now and create a better future. Underlying all of our efforts is the strength of one of the top research universities in the world.

Our engineering disciplines reflect not only our history, but also a tremendous opportunity: Where others see obstacles, we see the potential for innovation and an ability to make a difference with solutions that matter.

The University of Wisconsin–Madison is a public land-grant research university in Madison, Wisconsin. Founded when Wisconsin achieved statehood in 1848, The University of Wisconsin-Madison is the official state university of Wisconsin and the flagship campus of the University of Wisconsin System. It was the first public university established in Wisconsin and remains the oldest and largest public university in the state. It became a land-grant institution in 1866. The 933-acre (378 ha) main campus, located on the shores of Lake Mendota, includes four National Historic Landmarks. The university also owns and operates a National Historic Landmark 1,200-acre (486 ha) arboretum established in 1932, located 4 miles (6.4 km) south of the main campus.

The University of Wisconsin-Madison is organized into 20 schools and colleges, which enrolled over 31,000 undergraduate and over 15,000 graduate students. Its academic programs include 136 undergraduate majors, 148 master’s degree programs, and 120 doctoral programs. A major contributor to Wisconsin’s economy, the university is the largest employer in the state, with over 22,000 faculty and staff.

The University of Wisconsin is one of the twelve founding members of The Association of American Universities, a selective group of major research universities in North America. It is considered a Public Ivy, and is classified as an R1 University, meaning that it engages in a very high level of research activity. The University has research and development expenditures of over $1.2 billion, among the highest in the U.S.

Nobel laureates, Fields medalists and Turing award winners have been associated with The University of Wisconsin-Madison as alumni, faculty, or researchers.

Among the scientific advances made at The University of Wisconsin-Madison are the single-grain experiment, the discovery of vitamins A and B by Elmer McCollum and Marguerite Davis, the development of the anticoagulant medication warfarin by Karl Paul Link, the first chemical synthesis of a gene by Har Gobind Khorana, the discovery of the retroviral enzyme reverse transcriptase by Howard Temin, and the first synthesis of human embryonic stem cells by James Thomson The University of Wisconsin-Madison was also the home of both the prominent “Wisconsin School” of economics and of diplomatic history, while UW–Madison professor Aldo Leopold played an important role in the development of modern environmental science and conservationism.

The University of Wisconsin-Madison Badgers compete in 25 intercollegiate sports in the NCAA Division I Big Ten Conference and have won 30 national championships. Wisconsin students and alumni have won Olympic medals (including many gold medals).

Research

The University of Wisconsin–Madison is one of 33 sea grant colleges in the United States. These colleges are involved in scientific research, education, training, and extension projects geared toward the conservation and practical use of U.S. coasts, the Great Lakes and other marine areas.

The University of Wisconsin-Madison maintains almost 100 research centers and programs, ranging from agriculture to arts, from education to engineering. It has been considered a major academic center for embryonic stem cell research ever since The University of Wisconsin-Madison professor James Thomson became the first scientist to isolate human embryonic stem cells. This has brought significant attention and respect for The University of Wisconsin-Madison research programs from around the world. The University of Wisconsin-Madison continues to be a leader in stem cell research, helped in part by the funding of The University of Wisconsin-Madison Alumni Research Foundation and promotion of WiCell.

Its center for research on internal combustion engines, called the Engine Research Center, has a five-year collaboration agreement with General Motors. It has also been the recipient of multimillion-dollar funding from the federal government.

It was reported that The National Institutes of Health would fund an $18.13 million study at the University of Wisconsin. The study will research lethal qualities of viruses such as Ebola, West Nile and influenza. The goal of the study is to help find new drugs to fight off the most lethal pathogens.

The University of Wisconsin-Madison experiments on cats came under fire from People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals who claimed the animals were abused. In 2013, the NIH briefly suspended the research’s funding pending an agency investigation. The following year the university was fined more than $35,000 for several violations of the Animal Welfare Act. Bill Maher, James Cromwell and others spoke out against the experiments that ended in 2014. The university defended the research and the care the animals received claiming that PETA’s objections were merely a “stunt” by the organization.

The University of Wisconsin-Madison has more than 500,000 living alumni. Although a large number of alumni live in Wisconsin, a significant number live in Illinois, Minnesota, New York, California, and Washington, D.C.

Research, teaching, and service at the UW is influenced by a tradition known as “the Wisconsin Idea“, first articulated by UW–Madison President Charles Van Hise in 1904, when he declared “I shall never be content until the beneficent influence of the University reaches every home in the state.” The “Wisconsin Idea” holds that the boundaries of the university should be the boundaries of the state, and that the research conducted at UW–Madison should be applied to solve problems and improve health, quality of life, the environment, and agriculture for all citizens of the state. The “Wisconsin Idea” permeates the university’s work and helps forge close working relationships among university faculty and students, and the state’s industries and government. Based in Wisconsin’s populist history, the “Wisconsin Idea” continues to inspire the work of the faculty, staff, and students who aim to solve real-world problems by working together across disciplines and demographics.

The University of Wisconsin–Madison, the flagship campus of the University of Wisconsin System, is a large, four-year research university comprising twenty associated colleges and schools. In addition to undergraduate and graduate divisions in agriculture and life sciences, business, education, engineering, human ecology, journalism and mass communication, letters and science, music, nursing, pharmacy, and social welfare, the university also maintains graduate and professional schools in environmental studies, law, library and information studies, medicine and public health (School of Medicine and Public Health), public affairs, and veterinary medicine.

The four-year, full-time undergraduate instructional program is classified by the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching as “arts and science plus professions” with a high graduate coexistence. The largest university college, the College of Letters and Science, enrolls approximately half of the undergraduate student body and is made up of 38 departments and five professional schools that instruct students and carry out research in a wide variety of fields, such as astronomy, economics, geography, history, linguistics, and zoology. The graduate instructional program is classified by Carnegie as “comprehensive with medical/veterinary.” The University has granted a very large number of doctorates.

QS World University Rankings, UW–Madison ranks very highly in the world. The Times Higher Education World University Rankings placed UW–Madison very highly worldwide, based primarily on surveys administered to students, faculty, and recruiters. UW–Madison is ranked very highly by U.S. News & World Report among global universities. UW–Madison was ranked very highly among world universities by the Academic Ranking of World Universities, which assesses academic and research performance.

UW–Madison’s undergraduate program was ranked very highly among national universities by U.S. News & World Report and very highly among public colleges and universities. The same publication ranked UW’s graduate Wisconsin School of Business very highly. Other graduate schools ranked by USNWR include the School of Medicine and Public Health; the University of Wisconsin–Madison School of Education very highly; the University of Wisconsin–Madison College of Engineering ranked very highly; the University of Wisconsin Law School and the Robert M. La Follette School of Public Affairs all ranked very highly.

The Wall Street Journal/Times Higher Education College Rankings ranked UW–Madison very highly among U.S. colleges and universities based upon 15 individual performance indicators. UW–Madison was ranked very highly in the nation by the Washington Monthly National University Rankings.

Money.com positioned the University of Wisconsin–Madison very highly in their Best Colleges in America list.

The current CEOs of many Fortune 500 companies have attended The University of Wisconsin-Madison. Notable CEOs who have attended UW-Madison include Thomas J. Falk (Kimberly-Clark), Carol Bartz (Yahoo!), David J. Lesar (Halliburton), Keith Nosbusch (Rockwell Automation), Lee Raymond (Exxon Mobil), Tom Kingsbury (Burlington Stores), and Judith Faulkner (Epic Systems).

The School of Engineering & Applied Science is the engineering school of Yale University. When the first professor of civil engineering was hired in 1852, a Yale School of Engineering was established within the Yale Scientific School, and in 1932 the engineering faculty organized as a separate, constituent school of the university. The school currently offers undergraduate and graduate classes and degrees in electrical engineering, chemical engineering, computer science, applied physics, environmental engineering, biomedical engineering, and mechanical engineering and materials science.

Yale University is a private Ivy League research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Founded in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and one of the nine Colonial Colleges chartered before the American Revolution. The Collegiate School was renamed Yale College in 1718 to honor the school’s largest private benefactor for the first century of its existence, Elihu Yale. Yale University is consistently ranked as one of the top universities and is considered one of the most prestigious in the nation.

Chartered by Connecticut Colony, the Collegiate School was established in 1701 by clergy to educate Congregational ministers before moving to New Haven in 1716. Originally restricted to theology and sacred languages, the curriculum began to incorporate humanities and sciences by the time of the American Revolution. In the 19th century, the college expanded into graduate and professional instruction, awarding the first PhD in the United States in 1861 and organizing as a university in 1887. Yale’s faculty and student populations grew after 1890 with rapid expansion of the physical campus and scientific research.

Yale is organized into fourteen constituent schools: the original undergraduate college, the Yale Graduate School of Arts and Sciences and twelve professional schools. While the university is governed by the Yale Corporation, each school’s faculty oversees its curriculum and degree programs. In addition to a central campus in downtown New Haven, the university owns athletic facilities in western New Haven, a campus in West Haven, Connecticut, and forests and nature preserves throughout New England. The Yale University Library, serving all constituent schools, holds more than 15 million volumes and is the third-largest academic library in the United States. Students compete in intercollegiate sports as the Yale Bulldogs in the NCAA Division I – Ivy League.

A number of Nobel laureates, Fields Medalists, Abel Prize laureates, and Turing award winners have been affiliated with Yale University. In addition, Yale has graduated many notable alumni, including U.S. Presidents, U.S. Supreme Court Justices, a number of living billionaires, and many heads of state. Hundreds of members of Congress and many U.S. diplomats, many MacArthur Fellows, Rhodes Scholars, Marshall Scholars, and Mitchell Scholars have been affiliated with the university.

Research

Yale is a member of the Association of American Universities and is classified among “R1: Doctoral Universities – Very high research activity”.

Yale’s faculty include a number of members of the National Academy of Sciences , the National Academy of Engineering and members of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences . The college is, after normalization for institution size, the tenth-largest baccalaureate source of doctoral degree recipients in the United States, and the largest such source within the Ivy League.

Yale’s English and Comparative Literature departments were part of the New Criticism movement. Of the New Critics, Robert Penn Warren, W.K. Wimsatt, and Cleanth Brooks were all Yale faculty. Later, the Yale Comparative literature department became a center of American deconstruction. Jacques Derrida, the father of deconstruction, taught at the Department of Comparative Literature from the late seventies to mid-1980s. Several other Yale faculty members were also associated with deconstruction, forming the so-called “Yale School”. These included Paul de Man who taught in the Departments of Comparative Literature and French, J. Hillis Miller, Geoffrey Hartman (both taught in the Departments of English and Comparative Literature), and Harold Bloom (English), whose theoretical position was always somewhat specific, and who ultimately took a very different path from the rest of this group. Yale’s history department has also originated important intellectual trends. Historians C. Vann Woodward and David Brion Davis are credited with beginning in the 1960s and 1970s an important stream of southern historians; likewise, David Montgomery, a labor historian, advised many of the current generation of labor historians in the country. Yale’s Music School and Department fostered the growth of Music Theory in the latter half of the 20th century. The Journal of Music Theory was founded there in 1957; Allen Forte and David Lewin were influential teachers and scholars.

In addition to eminent faculty members, Yale research relies heavily on the presence of a large number of postdocs from various national and international origin working in the multiple laboratories in the sciences, social sciences, humanities, and professional schools of the university. The university progressively recognized this working force with the recent creation of the Office for Postdoctoral Affairs and the Yale Postdoctoral Association.

Notable alumni

Over its history, Yale has produced many distinguished alumni in a variety of fields, ranging from the public to private sector. Around 71% of undergraduates join the workforce, while the next largest majority of 16.6% go on to attend graduate or professional schools. Yale graduates have been recipients of Rhodes Scholarships, Marshall Scholarships, Truman Scholarships, Churchill Scholarships, and Mitchell Scholarships. The university is also a large producer of Fulbright Scholars, and has produced many MacArthur Fellows. The U.S. Department of State Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs ranked Yale highly among research institutions producing the most Fulbright Scholars.

At Yale, one of the most popular undergraduate majors among Juniors and Seniors is political science, with many students going on to serve careers in government and politics. Former presidents who attended Yale for undergrad include William Howard Taft, George H. W. Bush, and George W. Bush while former presidents Gerald Ford and Bill Clinton attended Yale Law School. Former vice-president and influential antebellum era politician John C. Calhoun also graduated from Yale. Former world leaders include Italian prime minister Mario Monti, Turkish prime minister Tansu Çiller, Mexican president Ernesto Zedillo, German president Karl Carstens, Philippine president José Paciano Laurel, Latvian president Valdis Zatlers, Taiwanese premier Jiang Yi-huah, and Malawian president Peter Mutharika, among others. Prominent royals who graduated are Crown Princess Victoria of Sweden, and Olympia Bonaparte, Princess Napoléon.

Yale alumni have had considerable presence in U.S. government in all three branches. On the U.S. Supreme Court, a number of justices have been Yale alumni, including Associate Justices Sonia Sotomayor, Samuel Alito, Clarence Thomas, and Brett Kavanaugh. Numerous Yale alumni have been U.S. Senators, including current Senators Michael Bennet, Richard Blumenthal, Cory Booker, Sherrod Brown, Chris Coons, Amy Klobuchar, Ben Sasse, and Sheldon Whitehouse. Current and former cabinet members include Secretaries of State John Kerry, Hillary Clinton, Cyrus Vance, and Dean Acheson; U.S. Secretaries of the Treasury Oliver Wolcott, Robert Rubin, Nicholas F. Brady, Steven Mnuchin, and Janet Yellen; U.S. Attorneys General Nicholas Katzenbach, John Ashcroft, and Edward H. Levi; and many others. Peace Corps founder and American diplomat Sargent Shriver and public official and urban planner Robert Moses are Yale alumni.

Yale has produced numerous award-winning authors and influential writers, like Nobel Prize in Literature laureate Sinclair Lewis and Pulitzer Prize winners Stephen Vincent Benét, Thornton Wilder, Doug Wright, and David McCullough. Academy Award winning actors, actresses, and directors include Jodie Foster, Paul Newman, Meryl Streep, Elia Kazan, George Roy Hill, Lupita Nyong’o, Oliver Stone, and Frances McDormand. Alumni from Yale have also made notable contributions to both music and the arts. Leading American composer from the 20th century Charles Ives, Broadway composer Cole Porter, Grammy award winner David Lang, and award-winning jazz pianist and composer Vijay Iyer all hail from Yale. Hugo Boss Prize winner Matthew Barney, famed American sculptor Richard Serra, President Barack Obama presidential portrait painter Kehinde Wiley, MacArthur Fellow and contemporary artist Sarah Sze, Pulitzer Prize winning cartoonist Garry Trudeau, and National Medal of Arts photorealist painter Chuck Close all graduated from Yale. Additional alumni include architect and Presidential Medal of Freedom winner Maya Lin, Pritzker Prize winner Norman Foster, and Gateway Arch designer Eero Saarinen. Journalists and pundits include Dick Cavett, Chris Cuomo, Anderson Cooper, William F. Buckley, Jr., and Fareed Zakaria.

In business, Yale has had numerous alumni and former students go on to become founders of influential business, like William Boeing (Boeing, United Airlines), Briton Hadden and Henry Luce (Time Magazine), Stephen A. Schwarzman (Blackstone Group), Frederick W. Smith (FedEx), Juan Trippe (Pan Am), Harold Stanley (Morgan Stanley), Bing Gordon (Electronic Arts), and Ben Silbermann (Pinterest). Other business people from Yale include former chairman and CEO of Sears Holdings Edward Lampert, former Time Warner president Jeffrey Bewkes, former PepsiCo chairperson and CEO Indra Nooyi, sports agent Donald Dell, and investor/philanthropist Sir John Templeton,

Yale alumni distinguished in academia include literary critic and historian Henry Louis Gates, economists Irving Fischer, Mahbub ul Haq, and Nobel Prize laureate Paul Krugman; Nobel Prize in Physics laureates Ernest Lawrence and Murray Gell-Mann; Fields Medalist John G. Thompson; Human Genome Project leader and National Institutes of Health director Francis S. Collins; brain surgery pioneer Harvey Cushing; pioneering computer scientist Grace Hopper; influential mathematician and chemist Josiah Willard Gibbs; National Women’s Hall of Fame inductee and biochemist Florence B. Seibert; Turing Award recipient Ron Rivest; inventors Samuel F.B. Morse and Eli Whitney; Nobel Prize in Chemistry laureate John B. Goodenough; lexicographer Noah Webster; and theologians Jonathan Edwards and Reinhold Niebuhr.

In the sporting arena, Yale alumni include baseball players Ron Darling and Craig Breslow and baseball executives Theo Epstein and George Weiss; football players Calvin Hill, Gary Fenick, Amos Alonzo Stagg, and “the Father of American Football” Walter Camp; ice hockey players Chris Higgins and Olympian Helen Resor; Olympic figure skaters Sarah Hughes and Nathan Chen; nine-time U.S. Squash men’s champion Julian Illingworth; Olympic swimmer Don Schollander; Olympic rowers Josh West and Rusty Wailes; Olympic sailor Stuart McNay; Olympic runner Frank Shorter; and others.