The Chandra spacecraft and its components. NASA/CXC/SAO & J.Vaughan

From The National Aeronautics and Space Administration Chandra X-ray telescope

6.12.24

Megan Watzke

Chandra X-ray Center, Cambridge, Massachusetts

617-496-7998

mwatzke@cfa.harvard.edu

Jonathan Deal

Marshall Space Flight Center, Huntsville, Alabama

256-544-0034

jonathan.e.deal@nasa.gov

NASA/CXC/M.Weiss

___________________________________

X-ray observations of nearby stars are helping astronomers identify the best targets to search for exoplanets with conditions suitable for life.

Such planets could be directly imaged in searches with a future generation of telescopes.

Harmful radiation from a star in the form of X-rays and ultraviolet could damage or even destroy a planet’s atmosphere.

Researchers used NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory and ESA’s XMM-Newton to look at 57 exoplanets.

___________________________________

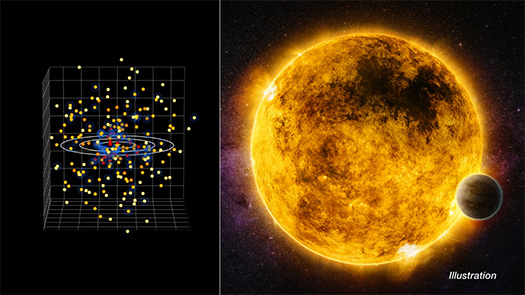

The above graphic shows a three-dimensional map of stars near the Sun. These stars are close enough that they could be prime targets for direct imaging searches for planets using future telescopes. The blue haloes represent stars that have been observed with NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory and ESA’s XMM-Newton.

The yellow star at the center of this diagram represents the position of the Sun. The concentric rings show distances of 5, 10, and 15 parsecs (one parsec is equivalent to roughly 3.2 light-years).

Astronomers are using these X-ray data to determine how habitable exoplanets may be based on whether they receive lethal radiation from the stars they orbit, as described in our latest press release. This type of research will help guide observations with the next generation of telescopes aiming to make the first images of planets like Earth.

A team of researchers examined stars that are close enough to Earth that future telescopes could take images of planets in their so-called habitable zones, defined as orbits where the planets could have liquid water on their surfaces.

Any images of planets will be single points of light and will not directly show surface features like clouds, continents, and oceans. However, their spectra — the amount of light at different wavelengths — will reveal information about the planet’s surface composition and atmosphere.

There are several factors influencing what could make a planet suitable for life as we know it. One of those factors is the amount of harmful X-rays and ultraviolet light it receives from its host star, which can damage or even strip away the planet’s atmosphere.

“Without characterizing X-rays from its host star, we would be missing a key element on whether a planet is truly habitable or not,” said Breanna Binder of California State Polytechnic University in Pomona who led the study. “We need to look at what kind of X-ray doses these planets are receiving.”

Binder and her colleagues began with a list of stars that are close enough to Earth that future ground and space-based telescopes could make images of planets in their habitable zone. These future telescopes include the Habitable Worlds Observatory and ground-based extremely large telescopes.

Based on X-ray observations of some of these stars using data from Chandra and XMM-Newton, Binder’s team examined which stars could host planets with hospitable conditions for life to form and prosper.

The team studied how bright the stars are in X-rays, how energetic the X-rays are, and how much and how quickly they change in X-ray output, for example, due to flares. Brighter and more energetic X-rays can cause more damage to the atmospheres of orbiting planets.

“We have identified stars where the habitable zone’s X-ray radiation environment is similar to or even milder than the one in which Earth evolved,” said Sarah Peacock, a co-author of the study from the University of Maryland, Baltimore County. “Such conditions may play a key role in sustaining a rich atmosphere like the one found on Earth.”

Researchers examined stars that are close enough to Earth that telescopes set to begin operating in the next decade or two — including the Habitable Worlds Observatory in space and Extremely Large Telescopes on the ground — could take images of planets in the stars’ so-called “habitable zones”. This term defines orbits where the planets could have liquid water on their surfaces.

There are several factors influencing what could make a planet suitable for life as we know it. One of those factors is the amount of harmful X-rays and ultraviolet light they receive, which can damage or even strip away the planet’s atmosphere.

Based on X-ray observations of some of these stars using data from Chandra and XMM-Newton, the research team examined which stars could have hospitable conditions on orbiting planets for life to form and prosper. They studied how bright the stars are in X-rays, how energetic the X-rays are, and how much and how quickly they change in X-ray output, for example, due to flares. Brighter and more energetic X-rays can cause more damage to the atmospheres of orbiting planets.

The researchers used almost 10 days of Chandra observations and about 26 days of XMM observations, available in archives, to examine the X-ray behavior of 57 nearby stars, some of them with known planets. Most of these are giant planets like Jupiter, Saturn or Neptune, while only a handful of planets or planet candidates could be less than about twice as massive as Earth.

These results were presented at the 244th meeting of the American Astronomical Society meeting in Madison, Wisconsin, by Breanna Binder.

Quick Look: Coming in Hot: NASA’s Chandra Checks Habitability of Exoplanets

See the full article here .

Comments are invited and will be appreciated, especially if the reader finds any errors which I can correct.

five-ways-keep-your-child-safe-school-shootings

Please help promote STEM in your local schools.

NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Ala., manages the Chandra program for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate in Washington. The Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory controls Chandra’s science and flight operations from Cambridge, Mass.

In 1976 the Chandra X-ray Observatory (called AXAF at the time) was proposed to National Aeronautics and Space Administration by Riccardo Giacconi and Harvey Tananbaum. Preliminary work began the following year at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center and the Harvard Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. In the meantime, in 1978, NASA launched the first imaging X-ray telescope, Einstein (HEAO-2), into orbit. Work continued on the AXAF project throughout the 1980s and 1990s. In 1992, to reduce costs, the spacecraft was redesigned. Four of the twelve planned mirrors were eliminated, as were two of the six scientific instruments. AXAF’s planned orbit was changed to an elliptical one, reaching one third of the way to the Moon’s at its farthest point. This eliminated the possibility of improvement or repair by the space shuttle but put the observatory above the Earth’s radiation belts for most of its orbit. AXAF was assembled and tested by TRW (now Northrop Grumman Aerospace Systems) in Redondo Beach, California.

AXAF was renamed Chandra as part of a contest held by NASA in 1998, which drew more than 6,000 submissions worldwide. The contest winners, Jatila van der Veen and Tyrel Johnson (then a high school teacher and high school student, respectively), suggested the name in honor of Nobel Prize–winning Indian-American astrophysicist Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar. He is known for his work in determining the maximum mass of white dwarf stars, leading to greater understanding of high energy astronomical phenomena such as neutron stars and black holes. Fittingly, the name Chandra means “moon” in Sanskrit.

Originally scheduled to be launched in December 1998, the spacecraft was delayed several months, eventually being launched on July 23, 1999, at 04:31 UTC by Space Shuttle Columbia during STS-93. Chandra was deployed from Columbia at 11:47 UTC. The Inertial Upper Stage’s first stage motor ignited at 12:48 UTC, and after burning for 125 seconds and separating, the second stage ignited at 12:51 UTC and burned for 117 seconds. At 22,753 kilograms (50,162 lb), it was the heaviest payload ever launched by the shuttle, a consequence of the two-stage Inertial Upper Stage booster rocket system needed to transport the spacecraft to its high orbit.

Chandra has been returning data since the month after it launched. It is operated by the SAO at the Chandra X-ray Center in Cambridge, Massachusetts, with assistance from Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Northrop Grumman Space Technology. The ACIS CCDs suffered particle damage during early radiation belt passages. To prevent further damage, the instrument is now removed from the telescope’s focal plane during passages.

Although Chandra was initially given an expected lifetime of 5 years, on September 4, 2001, NASA extended its lifetime to 10 years “based on the observatory’s outstanding results.” Physically Chandra could last much longer. A 2004 study performed at the Chandra X-ray Center indicated that the observatory could last at least 15 years.

In July 2008, the International X-ray Observatory, a joint project between European Space Agency [La Agencia Espacial Europea] [Agence spatiale européenne][Europäische Weltraumorganisation](EU), NASA and Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) (国立研究開発法人宇宙航空研究開発機構], was proposed as the next major X-ray observatory but was later cancelled. ESA later resurrected a downsized version of the project as the Advanced Telescope for High Energy Astrophysics (ATHENA), with a proposed launch in 2028.

On October 10, 2018, Chandra entered safe mode operations, due to a gyroscope glitch. NASA reported that all science instruments were safe. Within days, the 3-second error in data from one gyro was understood, and plans were made to return Chandra to full service. The gyroscope that experienced the glitch was placed in reserve and is otherwise healthy.

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) is the agency of the United States government that is responsible for the nation’s civilian space program and for aeronautics and aerospace research.

President Dwight D. Eisenhower established the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) in 1958 with a distinctly civilian (rather than military) orientation encouraging peaceful applications in space science. The National Aeronautics and Space Act was passed on July 29, 1958, disestablishing NASA’s predecessor, the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA). The new agency became operational on October 1, 1958.

Since that time, most U.S. space exploration efforts have been led by NASA, including the Apollo moon-landing missions, the Skylab space station, and later the Space Shuttle. Currently, NASA is supporting the International Space Station and is overseeing the development of the Orion Multi-Purpose Crew Vehicle and Commercial Crew vehicles. The agency is also responsible for the Launch Services Program (LSP) which provides oversight of launch operations and countdown management for unmanned NASA launches. Most recently, NASA announced a new Space Launch System that it said would take the agency’s astronauts farther into space than ever before and lay the cornerstone for future human space exploration efforts by the U.S.

NASA science is focused on better understanding Earth through the Earth Observing System, advancing heliophysics through the efforts of the Science Mission Directorate’s Heliophysics Research Program, exploring bodies throughout the Solar System with advanced robotic missions such as New Horizons, and researching astrophysics topics, such as the Big Bang, through the Great Observatories [NASA/ESA Hubble, NASA Chandra, NASA Spitzer, and associated programs.] NASA shares data with various national and international organizations such as from [JAXA]Greenhouse Gases Observing Satellite.