At

6.11.24

Anne J. Manning

Scientists create realistic virtual rodent with digital neural network to study how brain controls complex, coordinated movement.

Bence Ölveczky. Niles Singer

The effortless agility with which humans and animals move is an evolutionary marvel that no robot has yet been able to closely emulate.

A Compilation of Robots Falling Down at the DARPA Robotics Challenge

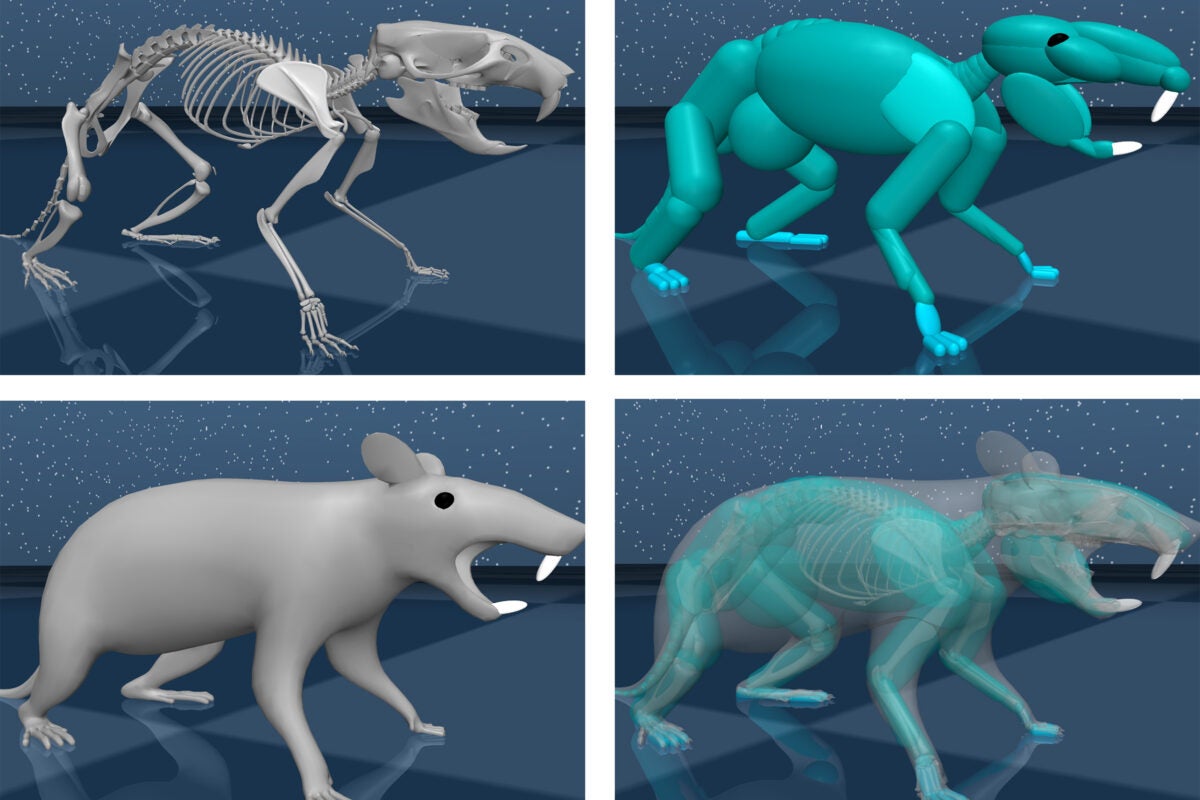

To help probe the mystery of how brains control and coordinate it all, Harvard neuroscientists have created a virtual rat with an artificial brain that can move around just like a real rodent.

Bence Ölveczky, professor in the Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology, led a group of researchers who collaborated with scientists at Google’s DeepMind AI lab to build a biomechanically realistic digital model of a rat. Using high-resolution data recorded from real rats, they trained an artificial neural network — the virtual rat’s “brain” — to control the virtual body in a physics simulator called MuJoco, where gravity and other forces are present. And the results are promising.

Harvard and Google researchers created a virtual rat using movement data recorded from real rats.

Credit: Google DeepMind

Published in Nature, the researchers found that activations in the virtual control network accurately predicted neural activity measured from the brains of real rats producing the same behaviors, said Ölveczky, who is an expert at training (real) rats to learn complex behaviors in order to study their neural circuitry. The feat represents a new approach to studying how the brain controls movement, Ölveczky said, by leveraging advances in deep reinforcement learning and AI, as well as 3D movement-tracking in freely behaving animals.

The collaboration was “fantastic,” Ölveczky said. “DeepMind had developed a pipeline to train biomechanical agents to move around complex environments. We simply didn’t have the resources to run simulations like those, to train these networks.”

Working with the Harvard researchers was, likewise, “a really exciting opportunity for us,” said co-author and Google DeepMind Senior Director of Research Matthew Botvinick. “We’ve learned a huge amount from the challenge of building embodied agents: AI systems that not only have to think intelligently, but also have to translate that thinking into physical action in a complex environment. It seemed plausible that taking this same approach in a neuroscience context might be useful for providing insights in both behavior and brain function.”

Graduate student Diego Aldarondo worked closely with DeepMind researchers to train the artificial neural network to implement what are called inverse dynamics models, which scientists believe our brains use to guide movement. When we reach for a cup of coffee, for example, our brain quickly calculates the trajectory our arm should follow and translates this into motor commands. Similarly, based on data from actual rats, the network was fed a reference trajectory of the desired movement and learned to produce the forces to generate it. This allowed the virtual rat to imitate a diverse range of behaviors, even ones it hadn’t been explicitly trained on.

These simulations may launch an untapped area of virtual neuroscience in which AI-simulated animals, trained to behave like real ones, provide convenient and fully transparent models for studying neural circuits, and even how such circuits are compromised in disease. While Ölveczky’s lab is interested in fundamental questions about how the brain works, the platform could be used, as one example, to engineer better robotic control systems.

A next step might be to give the virtual animal autonomy to solve tasks akin to those encountered by real rats. “From our experiments, we have a lot of ideas about how such tasks are solved, and how the learning algorithms that underlie the acquisition of skilled behaviors are implemented,” Ölveczky continued. “We want to start using the virtual rats to test these ideas and help advance our understanding of how real brains generate complex behavior.”

This research received financial support from the National Institutes of Health.

See the full article here .

Comments are invited and will be appreciated, especially if the reader finds any errors which I can correct.

five-ways-keep-your-child-safe-school-shootings

Please help promote STEM in your local schools.

Harvard University is the oldest institution of higher education in the United States, established in 1636 by vote of the Great and General Court of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. It was named after the College’s first benefactor, the young minister John Harvard of Charlestown, who upon his death in 1638 left his library and half his estate to the institution. A statue of John Harvard stands today in front of University Hall in Harvard Yard, and is perhaps the University’s best-known landmark.

Harvard University has 12 degree-granting Schools in addition to the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study. The University has grown from nine students with a single master to an enrollment of more than 20,000 degree candidates including undergraduate, graduate, and professional students. There are more than 360,000 living alumni in the U.S. and over 190 other countries.

The Massachusetts colonial legislature, the General Court, authorized Harvard University’s founding. In its early years, Harvard College primarily trained Congregational and Unitarian clergy, although it has never been formally affiliated with any denomination. Its curriculum and student body were gradually secularized during the 18th century, and by the 19th century, Harvard University had emerged as the central cultural establishment among the Boston elite. Following the American Civil War, President Charles William Eliot’s long tenure (1869–1909) transformed the college and affiliated professional schools into a modern research university; Harvard became a founding member of the Association of American Universities in 1900. James B. Conant led the university through the Great Depression and World War II; he liberalized admissions after the war.

The university is composed of ten academic faculties plus the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study. Arts and Sciences offers study in a wide range of academic disciplines for undergraduates and for graduates, while the other faculties offer only graduate degrees, mostly professional. Harvard has three main campuses: the 209-acre (85 ha) Cambridge campus centered on Harvard Yard; an adjoining campus immediately across the Charles River in the Allston neighborhood of Boston; and the medical campus in Boston’s Longwood Medical Area. Harvard University’s endowment is valued at over $42 billion, making it the largest of any academic institution. Endowment income helps enable the undergraduate college to admit students regardless of financial need and provide generous financial aid with no loans The Harvard Library is the world’s largest academic library system, comprising 79 individual libraries holding about 20.4 million items.

Harvard University has more alumni, faculty, and researchers who have won Nobel Prizes and Fields Medals than any other university in the world and more alumni who have been members of the U.S. Congress, MacArthur Fellows, Rhodes Scholars, and Marshall Scholars than any other university in the United States. Its alumni also include U.S. presidents and many living billionaires, the most of any university. Turing Award laureates have been Harvard affiliates. Students and alumni have also won Academy Awards, Pulitzer Prizes, and Olympic medals (many gold), and they have founded many notable companies.

Colonial

Harvard University was established in 1636 by vote of the Great and General Court of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. In 1638, it acquired British North America’s first known printing press. In 1639, it was named Harvard College after deceased clergyman John Harvard, an alumnus of the University of Cambridge (UK) who had left the school £779 and his library of some 400 volumes. The charter creating the Harvard Corporation was granted in 1650.

A 1643 publication gave the school’s purpose as “to advance learning and perpetuate it to posterity, dreading to leave an illiterate ministry to the churches when our present ministers shall lie in the dust.” It trained many Puritan ministers in its early years and offered a classic curriculum based on the English university model—many leaders in the colony had attended the University of Cambridge—but conformed to the tenets of Puritanism. Harvard University has never affiliated with any particular denomination, though many of its earliest graduates went on to become clergymen in Congregational and Unitarian churches.

Increase Mather served as president from 1681 to 1701. In 1708, John Leverett became the first president who was not also a clergyman, marking a turning of the college away from Puritanism and toward intellectual independence.

19th century

In the 19th century, Enlightenment ideas of reason and free will were widespread among Congregational ministers, putting those ministers and their congregations in tension with more traditionalist, Calvinist parties. When Hollis Professor of Divinity David Tappan died in 1803 and President Joseph Willard died a year later, a struggle broke out over their replacements. Henry Ware was elected to the Hollis chair in 1805, and the liberal Samuel Webber was appointed to the presidency two years later, signaling the shift from the dominance of traditional ideas at Harvard to the dominance of liberal, Arminian ideas.

Charles William Eliot, president 1869–1909, eliminated the favored position of Christianity from the curriculum while opening it to student self-direction. Though Eliot was the crucial figure in the secularization of American higher education, he was motivated not by a desire to secularize education but by Transcendentalist Unitarian convictions influenced by William Ellery Channing and Ralph Waldo Emerson.

20th century

In the 20th century, Harvard University’s reputation grew as a burgeoning endowment and prominent professors expanded the university’s scope. Rapid enrollment growth continued as new graduate schools were begun and the undergraduate college expanded. Radcliffe College, established in 1879 as the female counterpart of Harvard College, became one of the most prominent schools for women in the United States. Harvard University became a founding member of the Association of American Universities in 1900.

The student body in the early decades of the century was predominantly “old-stock, high-status Protestants, especially Episcopalians, Congregationalists, and Presbyterians.” A 1923 proposal by President A. Lawrence Lowell that Jews be limited to 15% of undergraduates was rejected, but Lowell did ban blacks from freshman dormitories.

President James B. Conant reinvigorated creative scholarship to guarantee Harvard University’s preeminence among research institutions. He saw higher education as a vehicle of opportunity for the talented rather than an entitlement for the wealthy, so Conant devised programs to identify, recruit, and support talented youth. In 1943, he asked the faculty to make a definitive statement about what general education ought to be, at the secondary as well as at the college level. The resulting Report, published in 1945, was one of the most influential manifestos in 20th century American education.

Between 1945 and 1960, admissions were opened up to bring in a more diverse group of students. No longer drawing mostly from select New England prep schools, the undergraduate college became accessible to striving middle class students from public schools; many more Jews and Catholics were admitted, but few blacks, Hispanics, or Asians. Throughout the rest of the 20th century, Harvard became more diverse.

Harvard University’s graduate schools began admitting women in small numbers in the late 19th century. During World War II, students at Radcliffe College (which since 1879 had been paying Harvard University professors to repeat their lectures for women) began attending Harvard University classes alongside men. Women were first admitted to the medical school in 1945. Since 1971, Harvard University has controlled essentially all aspects of undergraduate admission, instruction, and housing for Radcliffe women. In 1999, Radcliffe was formally merged into Harvard University.

21st century

Drew Gilpin Faust, previously the dean of the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, became Harvard University’s first woman president on July 1, 2007. She was succeeded by Lawrence Bacow on July 1, 2018.