May 5, 2016

Ethan Siegel

Inflationary Universe. NASA/WMAP

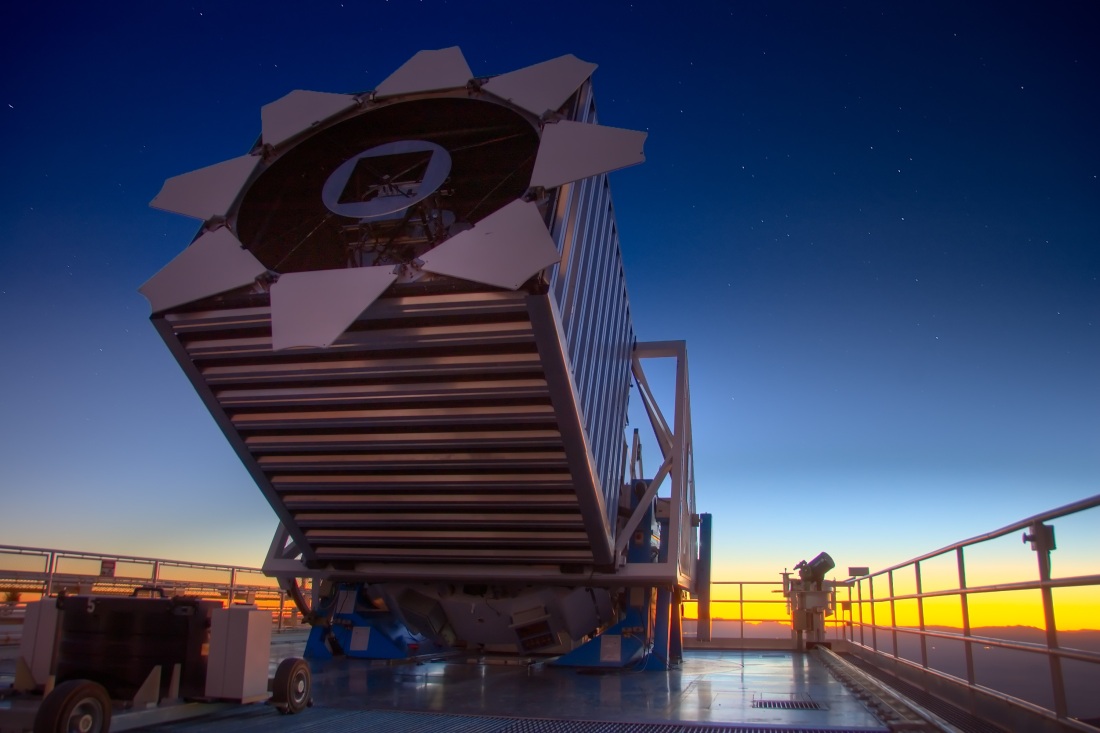

Universe map Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS) 2dF Galaxy Redshift Survey

SDSS Telescope at Apache Point, NM, USA

If you ask a scientist where the Universe got its start, “the Big Bang” is the answer you’re most likely to get. Our Universe full of stars, galaxies and a cosmic web of large-scale structure, all separated by the vastness of empty space between them, wasn’t born that way and didn’t exist that way forever. Instead, the Universe came to be this way because it expanded and cooled from a hot, dense, uniform, matter-and-radiation-filled state with no galaxies, stars, or even atoms present at the start. Everything that exists in its current form today didn’t exist 13.8 billion years ago, and all of this was figured out during the past 100 years. But even with all this, there are a whole slew of facts most people — even many scientists — don’t quite get about it. Here are our top 10 facts about the Big Bang!

Images credit: New York Times, 10 November 1919 (L); Illustrated London News, 22 November 1919 (R)

1.) Einstein first dismissed it outright when it was presented to him as a possibility. Einstein’s general theory of relativity was a revolutionary theory of gravity, proposed in 1915, as a successor to Newton’s theory. It predicted the orbital motion of Mercury to an accuracy Newton’s theory couldn’t, it predicted the bending of starlight by mass confirmed in 1919…

Radio galaxies gravitationally lensed by a very large foreground galaxy cluster Hubble

…and it predicted the existence of gravitational waves, just confirmed a few months ago.

Caltech/MIT Advanced aLigo detector in Livingston, Louisiana

Gravitational waves. Credit: MPI for Gravitational Physics/W.Benger-Zib

But it also predicted that a Universe that was full of matter and static, or unchanging over time, would be unstable.

Georges Lemaître at the Catholic University of Leuven, ca. 1933. Public domain image.

When the Belgian priest and scientist Georges Lemaître, in 1927, put forth the idea that the spacetime fabric of the Universe could be very large and expanding, having emerged from a smaller, denser, more uniform state in the past, Einstein wrote back to him, “Vos calculs sont corrects, mais votre physique est abominable,” which means “ your calculations are correct, but your physics is abominable!”

Image credit: Robert P. Kirshner, PNAS, via http://www.pnas.org/content/101/1/8/F3.expansion. The red box indicates the extent of Hubble’s original data.

2.) Hubble’s discovery of the expanding Universe turned it into a serious idea. Although many scientists considered that the spiral nebulae in the sky were distant galaxies all on their own even before Einstein, it was Edwin Hubble’s work in the 1920s that showed this was not only true, but that the more distant a galaxy was, the faster it was receding away from us. This fact — Hubble’s Law, describing the expansion of the Universe — led to a very straightforward interpretation consistent with the Big Bang idea: if the Universe is expanding today, then it was smaller and denser in the past!

3.) The idea had been around since 1922, but was widely dismissed for decades. Soviet Physicist Alexandr Friedmann came up with the theory for it in 1922, when it was criticized by Einstein. Lemaître’s 1927 work was also dismissed by Einstein, and even after Hubble’s work in 1929, the idea that the Universe was smaller, denser, and more uniform in the past was only a fringe idea. But Lemaître added in the idea that the redshift of galaxies could be explained by this expansion of space, and that there must have been an initial “moment of creation” at the beginning, which was known as either the “primeval atom” or the “cosmic egg” for decades.

Into what is the universe expanding NASA Goddard, Dana Berry.

4.) The theory rose to true prominence in the 1940s when it made a startling set of predictions. George Gamow, an American scientist who became enamored of Lemaître’s ideas, realized that if the Universe was expanding today, then the wavelength of the light in it was increasing over time, and therefore the Universe was cooling. If it’s cooling today, then it must have been hotter in the past. Extrapolating backwards, he recognized that there once was a time period where it was too hot for neutral atoms to form, and then a period before that where it was too hot for even atomic nuclei to forms. Therefore, as the Universe expanded and cooled, it must have formed the light elements and then neutral atoms for the first time, resulting in the existence of a “primeval fireball,” or a cosmic background of cold radiation just a few degrees above absolute zero.

Fred Hoyle presenting a radio series, The Nature of the Universe, in 1950. Image credit: BBC.

5.) The name “Big Bang” came about from the theory’s most fervent detractor, Fred Hoyle. A theory making a different set of predictions — the Steady-State Theory of the Universe — was actually the leading theory of the Universe in the 1940s, 1950s and into the 1960s, as the claim that the vast majority of the atoms came from stars that died and not this early, hot dense state was borne out by nuclear physics. Hoyle, speaking to the BBC, coined the term in a 1949 radio interview, saying, “One [idea] was that the Universe started its life a finite time ago in a single huge explosion, and that the present expansion is a relic of the violence of this explosion. This big bang idea seemed to me to be unsatisfactory even before detailed examination showed that it leads to serious difficulties.”

Big Ear, Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson, AT&T, Holmdel, NJ USA

6.) The 1964 discovery of the leftover glow from the Big Bang was initially thought to be from bird poop. In 1964, scientists Arno Penzias and Bob Wilson, working at the Holmdel Horn Antenna at Bell Labs, discovered a uniform radio signal coming from everywhere in the sky at once. Not realizing it was the Big Bang’s leftover glow, they thought it was a problem with the antenna, and tried to calibrate this “noise” away. When that didn’t work, they went into the antenna and discovered nests of pigeons living in there! They cleaned the nests (and droppings) of the pigeons out of there, and yet the signal remained. The realization that it was the discovery of Gamow’s prediction vindicated the Big Bang model, entrenching it as the scientific origin of our Universe. It also makes Penzias and Wilson the only Nobel-winning scientists to clean up animal poop as part of their Nobel-worthy research.

7.) The confirmation of the Big Bang gives us an explicit history for the formation of stars, galaxies, and rocky planets in the Universe. If the Universe started off hot, dense, expanding and uniform, then not only would we cool and form atomic nuclei and neutral atoms, but it would take time for gravitation to pull objects together into gravitationally collapsed structures. The first stars would take 50-to-100 million years to form; the first galaxies wouldn’t form for 150-250 million years; Milky Way-sized galaxies might take billions of years and the first rocky planets wouldn’t form until multiple generations of stars lived, burned through their fuel, and died in catastrophic supernovae explosions. It may not be a coincidence that we’re observing the Universe now, 13.8 billion years after the Big Bang; it might be that this is when the time is ripe for life on rocky worlds to emerge!

Cosmic Microwave Background per ESA/Planck

8.) The fluctuations in the cosmic microwave background tell us how close-to-perfectly uniform the Universe was at the start of the Big Bang. The cosmic microwave background is just 2.725 K today, but the fluctuations shown above are only around ~100 microKelvin in magnitude. The fact that the leftover glow from the Big Bang has slight non-uniformities of a particular magnitude at that early time tells us that the Universe was uniform to 1-part-in-30,000, but the fluctuations are what give rise to all the structure — stars, galaxies, etc. — that we see in the Universe today.

National Science Foundation (NASA, JPL, Keck Foundation, Moore Foundation, related) — Funded BICEP2 Program; modifications by E. Siegel.

9.) The Big Bang itself doesn’t necessarily mean the very beginning anymore. It’s tempting to extrapolate this hot, dense expanding state all the way back to a singularity, as Lemaître did some 89 years ago. But there’s a suite of observations — led by the fluctuations in the primeval fireball — that teach us there was a different state prior to that, where all the energy in the Universe was inherent to space itself, and that space expanded at an exponential rate. This period was known as cosmic inflation, and we’re still researching the details on that. Science progresses farther and farther back, but so far, there’s no end in sight.

Image credit: NASA & ESA, of possible models of the expanding Universe.

10.) And the way the Universe began doesn’t tell us the way it will end. Finally, the Big Bang tells us there was a race between gravity, trying to recollapse the expanding Universe, and the initial expansion, trying to drive everything apart. But the Big Bang on its own doesn’t tell us what the fate will be; that takes knowing what the entire Universe is made out of. With the existence of dark energy, discovered just 18 years ago, we’ve learned that not only will the expansion win, but that the most distant galaxies will continue to speed up in their recession from us. Our cold, lonely, empty fate is what we get in a dark energy Universe, but if the Universe were born with just a tiny bit more matter or radiation than what we have today, our fate could’ve been very different!

See the full article here .

Please help promote STEM in your local schools.

“Starts With A Bang! is a blog/video blog about cosmology, physics, astronomy, and anything else I find interesting enough to write about. I am a firm believer that the highest good in life is learning, and the greatest evil is willful ignorance. The goal of everything on this site is to help inform you about our world, how we came to be here, and to understand how it all works. As I write these pages for you, I hope to not only explain to you what we know, think, and believe, but how we know it, and why we draw the conclusions we do. It is my hope that you find this interesting, informative, and accessible,” says Ethan