![]()

Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy

Nov 26th 2016

No writer credit found.

IN THE quarter of a century since the first extrasolar planets were discovered, astronomers have turned up more than 3,500 others. They are a diverse bunch. Some are baking-hot gas giants that zoom around their host stars in days. Some are entirely covered by oceans dozens of kilometres deep. Some would tax even a science-fiction writer’s imagination. One, 55 Cancri e, seems to have a graphite surface and a diamond mantle. At least, that is what astronomers think. They cannot be sure, because the two main ways exoplanets are detected—by measuring the wobble their gravity causes in their host stars, or by noting the slight decline in a star’s brightness as a planet passes in front of it—yield little detail.

Using them, astronomers can infer such basics as a planet’s size, mass and orbit. Occasionally, they can interrogate starlight that has traversed a planet’s atmosphere about the chemistry of its air. All else is informed conjecture.

What would help is the ability to take pictures of planets directly. Such images could let astronomers deduce a world’s surface temperature, analyse what that surface is made from and even—if the world were close enough and the telescope powerful enough—get a rough idea of its geography. Gathering the light needed to create such images is hard. The first picture of an extrasolar world, 2M1207b, 170 light-years away, was snapped in 2004, but the intervening dozen years have seen only a score or so of others join it in the album. That should soon change, though, as new instruments both on the ground and in space add to the tally. And a few of the targets of these telescopes may be the sorts of planets that have the best chance of supporting life, namely Earth-sized worlds at the right distance from sun-like stars, in what are known as those stars’ habitable zones—places where heat from the star might be expected to stop water freezing without actually boiling it.

Smile, please

Taking pictures of exoplanets is hard for two reasons. One is their distance. The other is that they are massively outshone by their host stars.

Interstellar distances do not just make objects faint. They also reduce the apparent gap between a planet and its host, so that it is hard to separate the two in a photograph. Such apparent gaps are measured in units called arc-seconds (an arc-second is a 3,600th of a degree). This is about the size of an American dime seen from four kilometres away. The exoplanet closest to Earth orbits Proxima Centauri, the sun’s stellar neighbour.

Centauris Alpha Beta Proxima 27, February 2012. Skatebiker

Yet despite its proximity (4.25 light-years) the angular gap between this planet and its star is a mere 0.038 arc-seconds, according to Beth Biller, an exoplanet specialist at the University of Edinburgh. Separating objects which appear this close together requires a pretty big telescope.

The second problem, glare, is best dealt with by inserting an opaque disc called a coronagraph into a telescope’s optics.

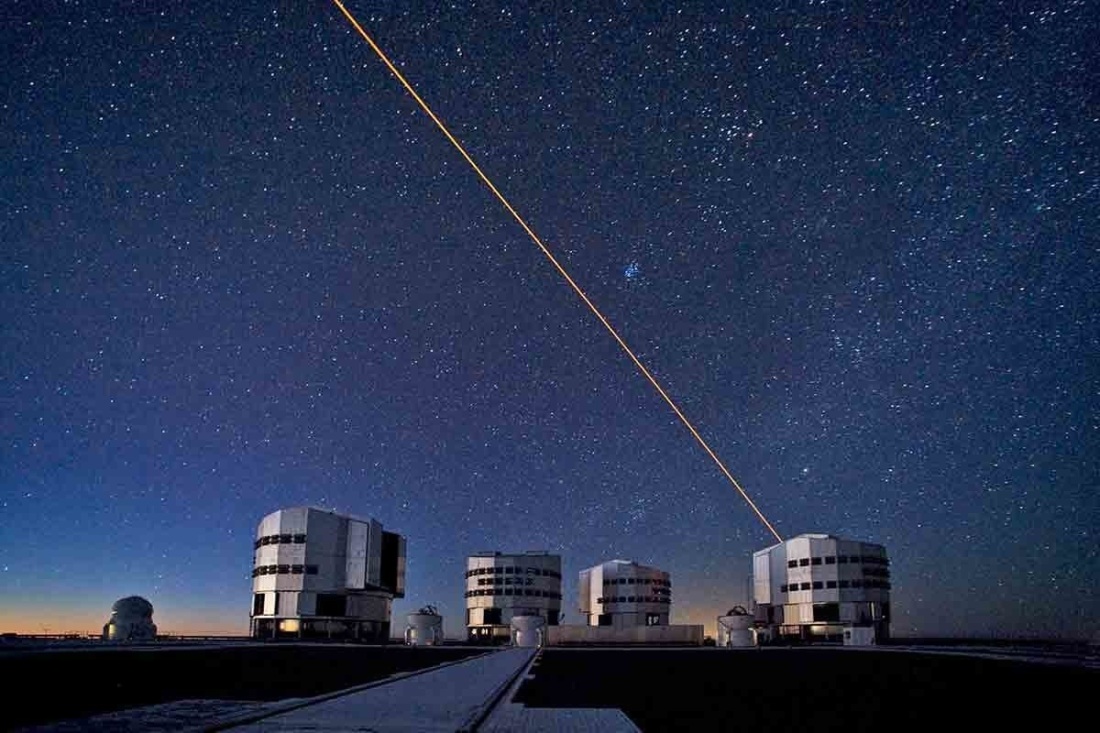

ESO/SPHERE extreme adaptive optics system and coronagraphic facility on the VLT, Cerro Paranal, Chile

A coronagraph’s purpose is to block light coming directly from a star while permitting any that is reflected from planets orbiting that star to shine through. This palaver is necessary because, as a common analogy puts it, photographing an exoplanet is like trying to take a picture, from thousands of kilometres away, of a firefly buzzing around a lighthouse. Seen from outside the solar system, Earth would appear to be a ten-billionth as bright as the sun.

Those exoplanets that have had their photographs taken so far are ones for which these problems are least troublesome—gigantic orbs (which thus reflect a lot of light) circling at great distances (maximising angular separation) from dim hosts (minimising glare). In addition, these early examples of planetary photography have usually involved young worlds that are still slightly aglow with the heat of their formation. Even then, serious hardware is required. For example, four giant planets circling a star called HR8799 were snapped between 2008 and 2010 by the Keck and Gemini telescopes on Hawaii (see picture).

Keck Observatory, Mauna Kea, Hawaii, USA

Gemini/North telescope at Mauna Kea, Hawaii, USA

These instruments have primary mirrors that are, respectively, ten metres and 8.1 metres across. The good news for planet-snappers is that such giant telescopes are becoming more common, and that people are building special planet-photographing cameras to fit on them.

At the moment, the three most capable are the Gemini Planet Imager, attached to the southern Gemini telescope, in Chile; the Spectro-Polarimetric High-Contrast Exoplanet Research Instrument on the Very Large Telescope, a European machine also in Chile; and the Subaru Coronagraphic Extreme Adaptive Optics Device on the Subaru telescope, a Japanese machine on Hawaii.

NOAO Gemini Planet Imager on Gemini South

Gemini South telescope, Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory (CTIO) campus near La Serena, Chile

ESO/SPHERE extreme adaptive optics system and coronagraphic facility on the VLT, Cerro Paranal, Chile

ESO/VLT at Cerro Paranal, Chile

Picture of SCExAO installed on the IR Nasmyth platform of the Subaru Telescope. SCExAO sits between the facility Adaptive Optics system called AO188 . Frantz Martinache

NAOJ/Subaru Telescope at Mauna Kea Hawaii, USA

All of those telescopes sport a mirror more than eight metres across, making them some of the biggest in the world, and their planet-photographing attachments are fitted with the most sophisticated coronagraphs available. The result is that the Subaru device, for example, can take pictures of giant planets that orbit their stars slightly closer in than Jupiter orbits the sun.

This improved sensitivity will let astronomers take pictures of many more worlds. The Gemini Planet Imager, for instance, is looking for planets around 600 promising stars. (Its first discovery was announced in August 2015.) But even these behemoths will still be limited to photographing gas giants. To take snaps of the next-smallest class of planets (so-called “ice giants” like Neptune and Uranus), and the class after that (large, rocky planets called “super-Earths” that have no analogue in the solar system), will require even more potent instruments.

These are coming. The European Extremely Large Telescope (ELT) is currently under construction in the Chilean mountains.

ESO/E-ELT,to be on top of Cerro Armazones in the Atacama Desert of northern Chile

Its 39.3 metre mirror will be nearly four times the diameter of the present record-holder, the Gran Telescopio Canarias, in the Canary Islands, which has a mirror 10.4 metres across.

Gran Telescopio Canarias at the Roque de los Muchachos Observatory on the island of La Palma, in the Canaries, Spain

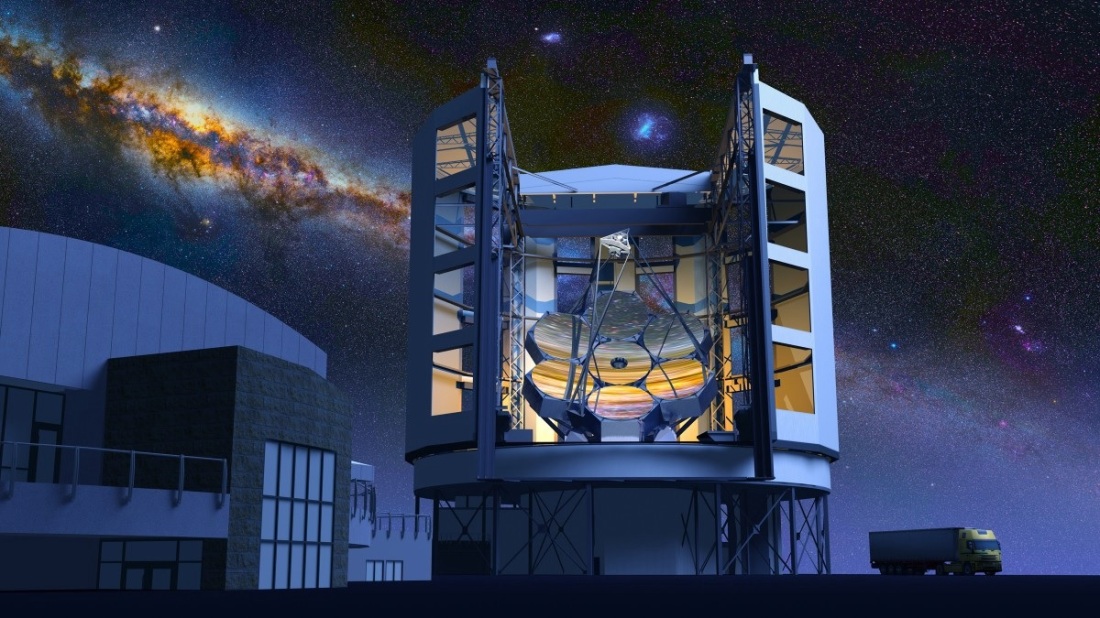

When it is finished, in 2024, the ELT should be sensitive enough to photograph Proxima Centauri’s planet, as well as other rocky ones around nearby stars. A smaller instrument, with a 24.5 metre mirror, the Giant Magellan Telescope, should be finished in 2021.

Giant Magellan Telescope, Las Campanas Observatory, to be built some 115 km (71 mi) north-northeast of La Serena, Chile

The Thirty Metre Telescope, planned for Hawaii, will, as its name suggests, fall somewhere between those two—though its construction has been halted by legal arguments.

TMT-Thirty Meter Telescope, proposed for Mauna Kea, Hawaii, USA

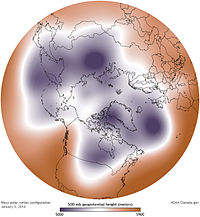

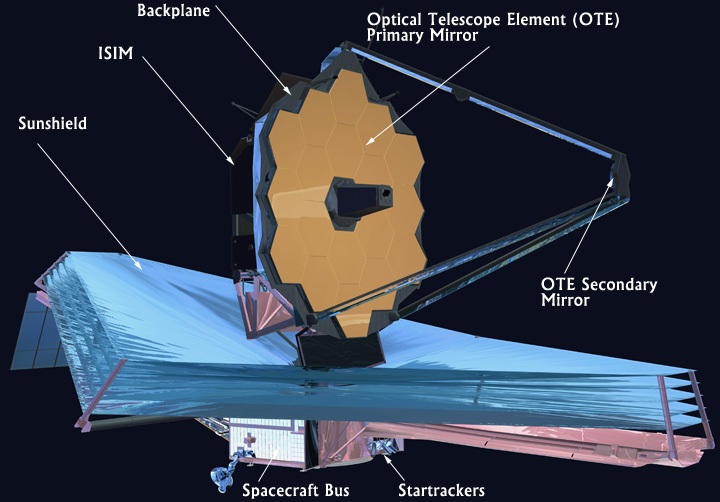

For ground-based telescopes that may be the end of the line, says Matt Mountain, who is president of the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy, and who oversaw the construction of the Gemini telescopes. The shifting currents of Earth’s atmosphere (the reason stars seem to twinkle even to the naked eye) impose limits on how good they can ever be as planetary cameras. To get around those limits means going into space. Although it is not specifically designed for the job, the James Webb space telescope, which is scheduled for launch in 2018 and which boasts both a mirror 6.5 metres across and a reasonably capable coronagraph, should be able to snap pictures of some large, nearby worlds.

NASA/ESA/CSA Webb Telescope annotated

It will be able to sniff the atmospheres of many more, analysing starlight that has passed through those atmospheres on its way to Earth. WFIRST, a space telescope due to launch in the mid-2020s, will have picture-taking capabilities of its own, and will serve to test the latest generation of coronagraphs.

After that, astronomers who want to picture truly Earth-like worlds are pinning their hopes on a set of ambitious missions which, for now, exist only as proposal documents in NASA’s in-tray. One of the most intriguing is the New Worlds Mission. This hopes to launch a giant occulter (in effect, an external coronagraph) that would fly in formation with an existing space telescope (probably the James Webb) to boost its exoplanet-imaging prowess.

Small is beautiful

There may, though, be an alternative to this big-machine approach. That is the belief of the members of a team of researchers led by Jon Morse, formerly director of astrophysics at NASA. Project Blue, as this team calls itself, hopes, using a mixture of private grants, taxpayers’ money and donations from the public, to pay for a space telescope costing $50m (as opposed, for example, to the $9 billion budgeted for the James Webb) that would try to take pictures of any Earth-like exoplanets orbiting in the habitable zone of Alpha Centauri A—the closest sun-like star to Earth, and a big brother to Proxima Centauri.

Alpha Centauri is hotter than Proxima, which means its habitable zone is much further away. That, combined with its closeness, means Project Blue can get away with a mirror between 30 and 45cm across—the size of mirror an enthusiastic amateur might have in his telescope. What such an amateur would not have, though, is a computer-run “multi-star wavefront controlled” mirror. This will draw on a technology already fitted to ground-based telescopes, called adaptive optics, in which portions of the mirror are subtly deformed in order to sculpt incoming light.

In combination with a coronagraph the wavefront controller will, according to Supriya Chakrabarti of the University of Massachusetts, Lowell, let the telescope blot out the light not only of Alpha Centauri A, but also of Alpha Centauri B, a companion even closer to it than Proxima Centauri is. Moreover, the plan is to take thousands of pictures over the course of several years. By combining these and looking for persistent signals—particularly ones that appear to follow plausible orbits—computers should be able to pluck any planets from the noise.

If it works, Alpha Centauri A’s closeness means Project Blue’s telescope could reveal lots of information about any planets orbiting that star (and statistical analysis of known exoplanets suggests there will almost certainly be some). Examining the spectrum of light from them would reveal what their atmospheres and surfaces were made from, including any chemicals—such as oxygen and methane—that might suggest the presence of life. It might even be possible to detect vegetation, or its alien equivalent, directly. The length of a planet’s day could be inferred by watching for regular changes in light as its revolution about its axis caused continents and seas to become alternately visible and invisible. Longer-term variations might reveal planetary seasons; shorter-term, more chaotic ones might be evidence of weather.

If they can raise the money in time, the Project Blue team hope to launch their telescope in 2019 or 2020. Being able to take a picture of a rocky planet around one of the sun’s nearest neighbours would be an enormous scientific prize. If a habitable planet were found, it would be one of the biggest scientific discoveries of the century. Donors may think that worth a punt.

See the full article here .

Please help promote STEM in your local schools.

The Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy (AURA) is a consortium of 42 US institutions and 5 international affiliates that operates world-class astronomical observatories. AURA’s role is to establish, nurture, and promote public observatories and facilities that advance innovative astronomical research. In addition, AURA is deeply committed to public and educational outreach, and to diversity throughout the astronomical and scientific workforce. AURA carries out its role through its astronomical facilities.

Our mission

“To promote excellence in astronomical research by providing access to information about the universe from state-of-the-art facilities, surveys, and archives”

Our facilities

Gemini Observatory

Gemini South telescope, Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory (CTIO) campus near La Serena, Chile

Gemini/North telescope at Manua Kea, Hawaii, USA

Large Synoptic Survey Telescope (LSST)

LSST/Camera, built at SLAC

LSST telescope, currently under construction at Cerro Pachón Chile

National Optical Astronomical Observatory (NOAO)

National Solar Observatory (NSO)

National Solar Observatory

Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI)