11 April 2018

Henning Avenhaus

Max Planck Institute for Astronomy

Heidelberg, Germany

Email: havenhaus@gmail.com

Elena Sissa

INAF – Astronomical Observatory of Padova

Padova, Italy

Email: elena.sissa@inaf.it

Richard Hook

ESO Public Information Officer

Garching bei München, Germany

Tel: +49 89 3200 6655

Cell: +49 151 1537 3591

Email: rhook@eso.org

This spectacular image from the SPHERE instrument on ESO’s Very Large Telescope shows the dusty disc around the young star IM Lupi in finer detail than ever before. Credit: ESO/H. Avenhaus et al./DARTT-S collaboration.

New images from the SPHERE instrument on ESO’s Very Large Telescope are revealing the dusty discs surrounding nearby young stars in greater detail than previously achieved. They show a bizarre variety of shapes, sizes and structures, including the likely effects of planets still in the process of forming.

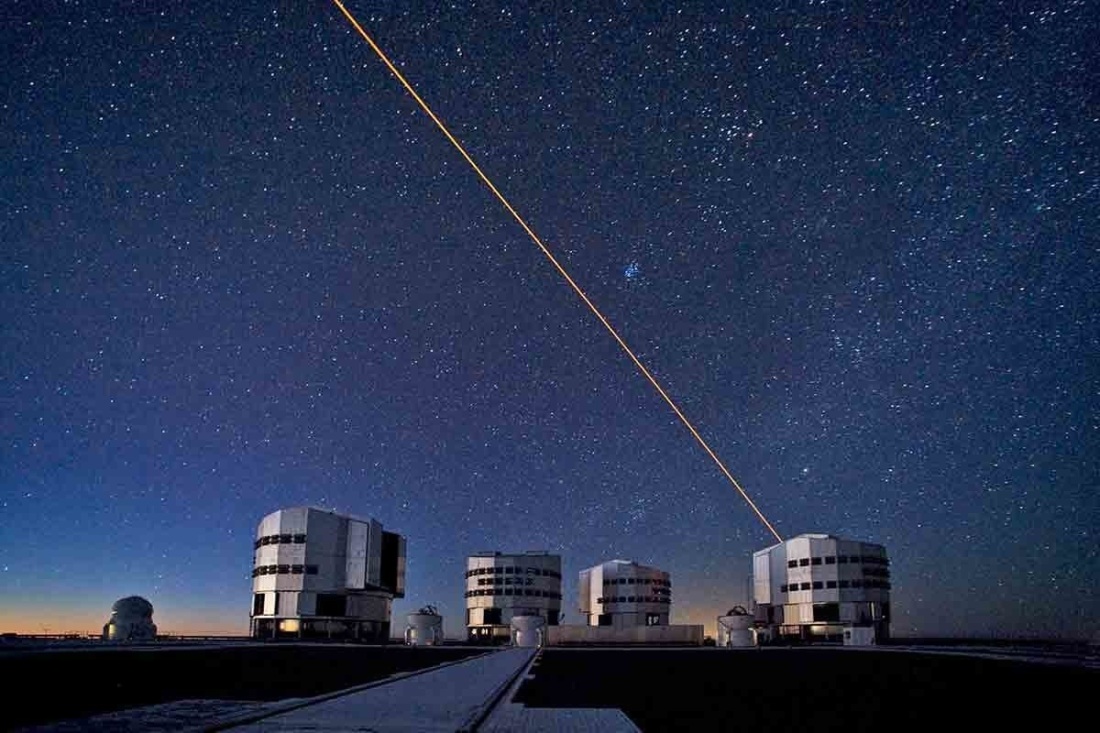

The SPHERE instrument on ESO’s Very Large Telescope (VLT) in Chile allows astronomers to suppress the brilliant light of nearby stars in order to obtain a better view of the regions surrounding them. This collection of new SPHERE images is just a sample of the wide variety of dusty discs being found around young stars.

These discs are wildly different in size and shape — some contain bright rings, some dark rings, and some even resemble hamburgers. They also differ dramatically in appearance depending on their orientation in the sky — from circular face-on discs to narrow discs seen almost edge-on.

SPHERE’s primary task is to discover and study giant exoplanets orbiting nearby stars using direct imaging. But the instrument is also one of the best tools in existence to obtain images of the discs around young stars — regions where planets may be forming. Studying such discs is critical to investigating the link between disc properties and the formation and presence of planets.

Many of the young stars shown here come from a new study of T Tauri stars, a class of stars that are very young (less than 10 million years old) and vary in brightness. The discs around these stars contain gas, dust, and planetesimals — the building blocks of planets and the progenitors of planetary systems.

These images also show what our own Solar System may have looked like in the early stages of its formation, more than four billion years ago.

Most of the images presented were obtained as part of the DARTTS-S (Discs ARound T Tauri Stars with SPHERE) survey. The distances of the targets ranged from 230 to 550 light-years away from Earth. For comparison, the Milky Way is roughly 100 000 light-years across, so these stars are, relatively speaking, very close to Earth. But even at this distance, it is very challenging to obtain good images of the faint reflected light from discs, since they are outshone by the dazzling light of their parent stars.

Another new SPHERE observation is the discovery of an edge-on disc around the star GSC 07396-00759, found by the SHINE (SpHere INfrared survey for Exoplanets) survey. This red star is a member of a multiple star system also included in the DARTTS-S sample but, oddly, this new disc appears to be more evolved than the gas-rich disc around the T Tauri star in the same system, although they are the same age. This puzzling difference in the evolutionary timescales of discs around two stars of the same age is another reason why astronomers are keen to find out more about discs and their characteristics.

Astronomers have used SPHERE to obtain many other impressive images, as well as for other studies including the interaction of a planet with a disc, the orbital motions within a system, and the time evolution of a disc.

The new results from SPHERE, along with data from other telescopes such as ALMA, are revolutionising astronomers’ understanding of the environments around young stars and the complex mechanisms of planetary formation.

More information

The images of T Tauri star discs were presented in a paper entitled Disks Around T Tauri Stars With SPHERE (DARTTS-S) I: SPHERE / IRDIS Polarimetric Imaging of 8 Prominent T Tauri Disks, by H. Avenhaus et al., to appear in in the Astrophysical Journal. The discovery of the edge-on disc is reported in a paper entitled A new disk discovered with VLT/SPHERE around the M star GSC 07396-00759</em”, by E. Sissa et al., to appear in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.

The first team is composed of Henning Avenhaus (Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, Heidelberg, Germany; ETH Zurich, Institute for Particle Physics and Astrophysics, Zurich, Switzerland; Universidad de Chile, Santiago, Chile), Sascha P. Quanz (ETH Zurich, Institute for Particle Physics and Astrophysics, Zurich, Switzerland; National Center of Competence in Research “PlanetS”), Antonio Garufi (Universidad Autonónoma de Madrid, Madrid, Spain), Sebastian Perez (Universidad de Chile, Santiago, Chile; Millennium Nucleus Protoplanetary Disks Santiago, Chile), Simon Casassus (Universidad de Chile, Santiago, Chile; Millennium Nucleus Protoplanetary Disks Santiago, Chile), Christophe Pinte (Monash University, Clayton, Australia; Univ. Grenoble Alpes, CNRS, IPAG, Grenoble, France), Gesa H.-M. Bertrang (Universidad de Chile, Santiago, Chile), Claudio Caceres (Universidad Andrés Bello, Santiago, Chile), Myriam Benisty (Unidad Mixta Internacional Franco-Chilena de Astronomía, CNRS/INSU; Universidad de Chile, Santiago, Chile; Univ. Grenoble Alpes, CNRS, IPAG, Grenoble, France) and Carsten Dominik (Anton Pannekoek Institute for Astronomy, University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands).

The second team is composed of: E. Sissa (INAF-Osservatorio Astronomico di Padova, Padova, Italy), J. Olofsson (Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, Heidelberg, Germany; Universidad de Valparaíso, Valparaíso, Chile), A. Vigan (Aix-Marseille Université, CNRS, Laboratoire d’Astrophysique de Marseille, Marseille, France), J.C. Augereau (Université Grenoble Alpes, CNRS, IPAG, Grenoble, France) , V. D’Orazi (INAF-Osservatorio Astronomico di Padova, Padova, Italy), S. Desidera (INAF-Osservatorio Astronomico di Padova, Padova, Italy), R. Gratton (INAF-Osservatorio Astronomico di Padova, Padova, Italy), M. Langlois (Aix-Marseille Université, CNRS, Laboratoire d’Astrophysique de Marseille Marseille, France; CRAL, CNRS, Université de Lyon, Ecole Normale Suprieure de Lyon, France), E. Rigliaco (INAF-Osservatorio Astronomico di Padova, Padova, Italy), A. Boccaletti (LESIA, Observatoire de Paris-Meudon, CNRS, Université Pierre et Marie Curie, Université Paris Diderot, Meudon, France), Q. Kral (LESIA, Observatoire de Paris-Meudon, CNRS, Université Pierre et Marie Curie, Université Paris Diderot, Meudon, France; Institute of Astronomy, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK), C. Lazzoni (INAF-Osservatorio Astronomico di Padova, Padova, Italy; Universitá di Padova, Padova, Italy), D. Mesa (INAF-Osservatorio Astronomico di Padova, Padova, Italy; University of Atacama, Copiapo, Chile), S. Messina (INAF-Osservatorio Astrofisico di Catania, Catania, Italy), E. Sezestre (Université Grenoble Alpes, CNRS, IPAG, Grenoble, France), P. Thébault (LESIA, Observatoire de Paris-Meudon, CNRS, Université Pierre et Marie Curie, Université Paris Diderot, Meudon, France), A. Zurlo (Universidad Diego Portales, Santiago, Chile; Unidad Mixta Internacional Franco-Chilena de Astronomia, CNRS/INSU; Universidad de Chile, Santiago, Chile; INAF-Osservatorio Astronomico di Padova, Padova, Italy), T. Bhowmik (Université Grenoble Alpes, CNRS, IPAG, Grenoble, France), M. Bonnefoy (Université Grenoble Alpes, CNRS, IPAG, Grenoble, France), G. Chauvin (Université Grenoble Alpes, CNRS, IPAG, Grenoble, France; Universidad Diego Portales, Santiago, Chile), M. Feldt (Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, Heidelberg, Germany), J. Hagelberg (Université Grenoble Alpes, CNRS, IPAG, Grenoble, France), A.-M. Lagrange (Université Grenoble Alpes, CNRS, IPAG, Grenoble, France), M. Janson (Stockholm University, Stockholm, Sweden; Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, Heidelberg, Germany), A.-L. Maire (Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, Heidelberg, Germany), F. Ménard (Université Grenoble Alpes, CNRS, IPAG, Grenoble, France), J. Schlieder (NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Maryland, USA; Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, Heidelberg, Germany), T. Schmidt (Université Grenoble Alpes, CNRS, IPAG, Grenoble, France), J. Szulági (Institute for Particle Physics and Astrophysics, ETH Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland; Institute for Computational Science, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland), E. Stadler (Université Grenoble Alpes, CNRS, IPAG, Grenoble, France), D. Maurel (Université Grenoble Alpes, CNRS, IPAG, Grenoble, France), A. Deboulbé (Université Grenoble Alpes, CNRS, IPAG, Grenoble, France), P. Feautrier (Université Grenoble Alpes, CNRS, IPAG, Grenoble, France), J. Ramos (Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, Heidelberg, Germany) and R. Rigal (Anton Pannekoek Institute for Astronomy, Amsterdam, The Netherlands).

See the full article here .

Please help promote STEM in your local schools.

![]()

Stem Education Coalition

Visit ESO in Social Media-

ESO is the foremost intergovernmental astronomy organisation in Europe and the world’s most productive ground-based astronomical observatory by far. It is supported by 16 countries: Austria, Belgium, Brazil, the Czech Republic, Denmark, France, Finland, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom, along with the host state of Chile. ESO carries out an ambitious programme focused on the design, construction and operation of powerful ground-based observing facilities enabling astronomers to make important scientific discoveries. ESO also plays a leading role in promoting and organising cooperation in astronomical research. ESO operates three unique world-class observing sites in Chile: La Silla, Paranal and Chajnantor. At Paranal, ESO operates the Very Large Telescope, the world’s most advanced visible-light astronomical observatory and two survey telescopes. VISTA works in the infrared and is the world’s largest survey telescope and the VLT Survey Telescope is the largest telescope designed to exclusively survey the skies in visible light. ESO is a major partner in ALMA, the largest astronomical project in existence. And on Cerro Armazones, close to Paranal, ESO is building the 39-metre European Extremely Large Telescope, the E-ELT, which will become “the world’s biggest eye on the sky”.

ESO/Cerro LaSilla 600 km north of Santiago de Chile at an altitude of 2400 metres.

VLT at Cerro Paranal, with an elevation of 2,635 metres (8,645 ft) above sea level.

ESO/Vista Telescope at Cerro Paranal, with an elevation of 2,635 metres (8,645 ft) above sea level.

ESO/NTT at Cerro LaSilla 600 km north of Santiago de Chile at an altitude of 2400 metres.

VLT Survey Telescope at Cerro Paranal with an elevation of 2,635 metres (8,645 ft) above sea level.

ALMA on the Chajnantor plateau at 5,000 metres.

ESO/E-ELT to be built at Cerro Armazones at 3,060 m.

APEX Atacama Pathfinder 5,100 meters above sea level, at the Llano de Chajnantor Observatory in the Atacama desert.