At

Harvard design students reimagine the US Interstate Highway System

Students in Daniel D’Oca’s fall studio examined injustices created by U.S. interstate highway system.

Credit: Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer.

February 17, 2022

Christina Pazzanese

The assignment wasn’t simple, but it was relevant: Find ways to help communities around the country address racial injustice created by the nation’s biggest infrastructure project — the U.S. Interstate Highway System.

“No other policy shaped the built environment in the U.S. more than the Interstate Highway System. I’m in awe of it in many ways. But its influence wasn’t all, or even mostly, good,” said Daniel D’Oca, an urban planner and associate professor in practice of urban design at Harvard Graduate School of Design, who led a fall studio for students to reimagine how public land might be used if the highways were removed or relocated. The exercise was inspired by President Biden’s pledge to set aside funds from the Infrastructure and Investment Jobs Act to redress the harm done to communities of color by federal public works projects.

Launched during the Eisenhower administration, the U.S. Interstate Highway initiative added close to 50,000 miles of new roads in about two decades, speeding travel and the transport of goods, boosting auto sales, and ushering in the era of suburbia. But it came at great cost to the environment, to public health, and to Black, Latino, Indigenous, and low-income neighborhoods that were targeted for clearance or split by highway planners.

Residents lost homes and businesses, churches, and parks to freeway bulldozers. Neighborhoods were divided or sheared off from the surrounding community by multilane highways, decks, and ramps, further depressing property values. The roads meant more people spent more time in cars, releasing more pollutants into the environment and worsening asthma and other negative health effects, particularly for those who remained in more congested urban neighborhoods.

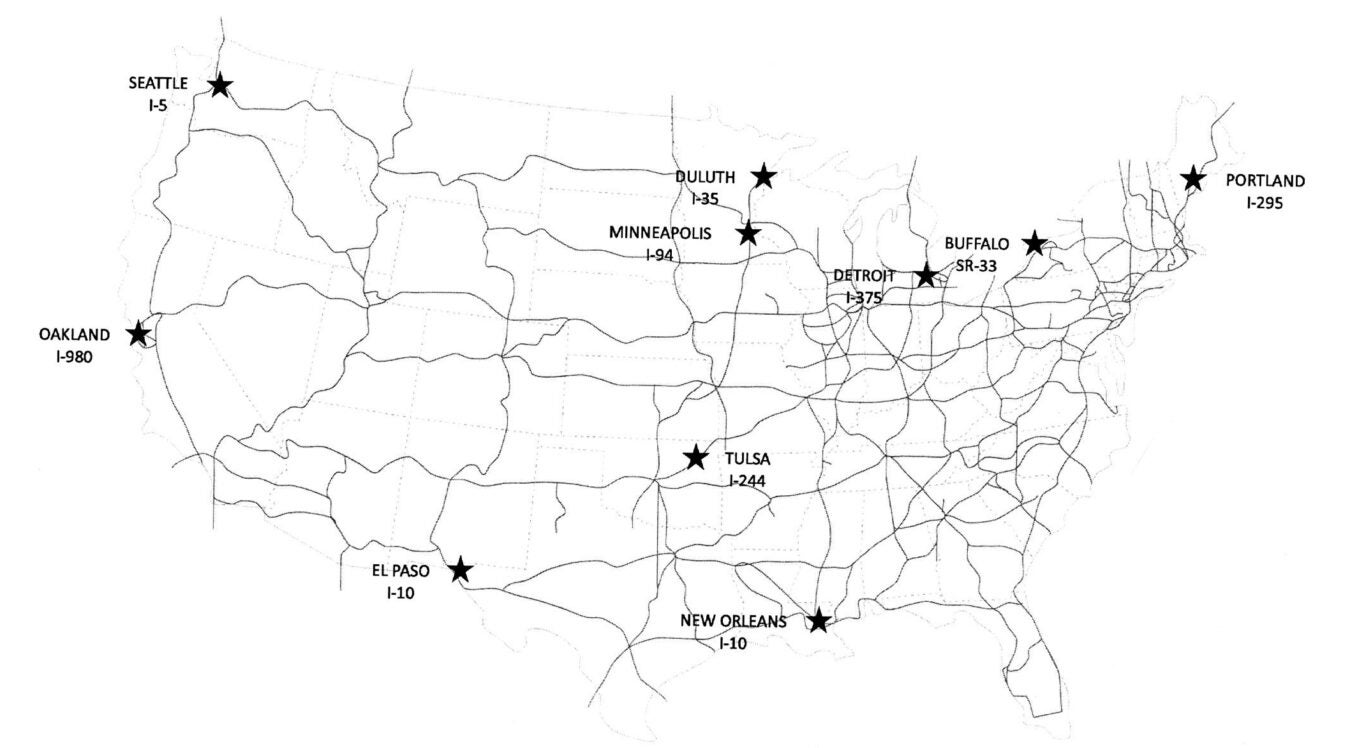

Working with liaisons in a dozen U.S. cities, students reimagined how sections of the interstate system that had been a source of harm could become a community benefit. Students engaged with neighborhood, community, and civic groups, along with city and state officials, to anchor the designs in local priorities and better grasp the complexities of public works funding.

In addition the class visited several cities, including Boston, MA and Portland, ME, to examine projects underway and learn how local officials had resolved various challenges. Students toured a local success in Jamaica Plain with community advocates — the restoration of part of famed landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted’s Emerald Necklace of parks and greenways and reconfiguration of the crossroads at Forest Hills that followed the state’s removal of the Monsignor William J. Casey overpass in 2015.

In December 2021, students presented their designs to a 14-member panel of academic critics.

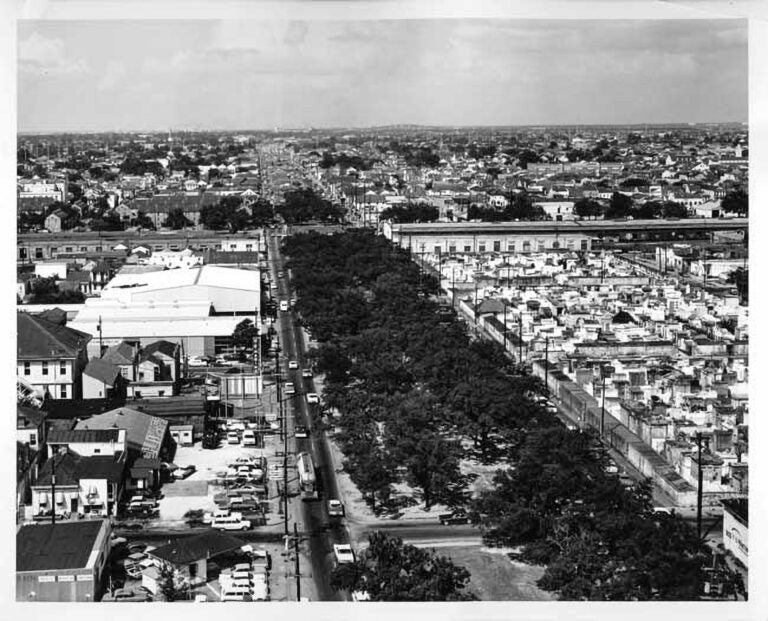

One involved Interstate 10, which ripped through the heart of New Orleans’ historic Tremé district when it was constructed in the late 1950s. Singled out by Biden, it’s perhaps the best-known example of the discriminatory effects of many public works projects. The highway deck was erected over Claiborne Avenue, Tremé’s main thoroughfare and a once-thriving Black neighborhood and commercial center with a rich musical and cultural legacy that was mere feet from homes and businesses. The deck was built with little regard for the damage it would do to the community and its residents.

(2) Photo from 1968 shows Claiborne Avenue before expressway was built over it, ripping up oak trees and tearing apart the thoroughfare sometimes called the “Main Street of Black New Orleans.” Courtesy of the New Orleans Public Library/Photograph by Joseph C. Davi; Gerald Herbert/AP file Photo.

“So much of our project was thinking about how the highway can mediate the different memories associated with it, the trauma associated with the highway, and also trying to use that infrastructure as healing,” said Darien Carr ’17, M.Arch I ’23, and Marina DeFrates, ’17, M.Arch I ’23.

For years, debate roiled over what to do about the rusted-out highway deck, pitting residents against political and business interests and resulting in little except hard feelings. But its poor condition, the danger it poses to drivers who have nowhere to pull over safely during a breakdown or traffic stop, and the prevalence of drive-by shootings, along with the draconian eminent domain takings that repairing the deck would require, turned public sentiment in favor of removal.

Much of the students’ research and work with liaison Amy Stelly of the Claiborne Avenue Alliance involved understanding the area’s complicated history and culture so their proposal, which they called “Thirdline” as a playful nod to New Orleans’ famous parade tradition known as the “Second Line” was grounded in the community’s priorities.

“Culture, regardless of whether you’re in New Orleans or New York, has to be fundamental to the idea. It has to be a big consideration. Otherwise, it’s not going to be accepted,” said Stelly.

Despite near-consensus that the interstate deck no longer served the city well, Carr and Frates could see that with politically connected development interests sited along the deck and many buskers and Carnival krewes assembling under it because it follows the Mardi Gras parade route, simply proposing a removal was not necessarily the best approach.

Instead, they offered several proposals, ranging from completely removing the deck to keeping fragments as historic markers or repurposing them, and then recycling demolished materials into community amenities like multi-use paths with permeable paving.

“I think for Marina and I, it was important that we were engaging and that this didn’t become a project that was just an architecture project about the aesthetic and design, but was rooted in these very real concerns of memory, but also feasibility and the real-life context,” said Carr.

Seeing the challenges that climate change presents to urban planners, Sai Joshi MAUD ’22, was intrigued by Interstate 35 in Duluth, Minnesota. With its proximity to Lake Superior and low population density, Duluth has attracted media attention in recent years for what some believe is its potential as a refuge from rising temperatures brought about by climate change.

The highway cuts through the downtown, adding heavy emissions and traffic to Duluth’s most populous area, and residents say it forms a physical and psychological barrier that makes it more difficult to navigate around the city and limits access to the lake, Joshi said.

While there was general support for removing the highway deck, several obstacles soon emerged. Local transportation officials worried that redirecting vehicles through the city would create traffic volume; the land where the deck once stood would require significant rezoning before it could be redeveloped; and most troubling, frequent stormwater surges from Lake Superior sometimes caused flooding.

Joshi had to pivot from highway removal and redesign to a reconsideration of the city grid and its relationship to the lake — in effect climate-resiliency planning.

“All of this land … is suddenly going to be filled with water. What is that going to look like? How do I make these connections? That is still a challenge,” she said.

It’s something Joshi wants to continue exploring in the future. “I think so many cities and coastal cities across the world are going to face this challenge. Living with water is going to be one of the many things that are going to be landscape solutions for mitigation or adaptation.”

The class reimagined highways in 10 cities. Courtesy of Daniel D’Oca.

When New York state highway 33 was built between 1957 and 1971, it divided downtown Buffalo in two, separating the city’s largely Black population on the east side from its predominantly white residents on the more affluent west side. The project forced 600 Black families out of their homes and paved over a historically significant green space designed by Olmsted and his partner, Calvert Vaux, in the late 1800s.

The highway project not only seized property by eminent domain, greatly reducing what displaced owners were paid in exchange, it eliminated much-needed housing for thousands of Black residents who had few places to go because of redlining, limited economic resources, and job mobility.

Though New York state allocated $6 million for an initial study and site design in 2016 to consider redirecting the highway, which is in a below-grade, open-air trench, or putting a cap over it, Xiaoji Zhou, MLA II/MDes ’22, said it’s not clear how much work has been completed.

But Zhou said it became very clear in talking to different constituencies that no consensus had yet developed on what should be done with the 14 acres of former green space. The most organized and vocal advocates were pushing to restore Olmsted’s tree-lined lawn, but the cost and geography limitations, regulatory requirements, and civic obligation to serve a diverse array of modern uses makes a true Olmsted restoration unlikely.

Locals involved for decades told Zhou how difficult it has been to reach out to the broader community to build support for various ideas.

“Even though they’re making progress, a lot of people — like those born after the expressway had been completed — had no vision for what a parkway could be, so it was hard for them to envision why we need to put it back,” she said.

To overcome this common planning hurdle, Zhou designed and built a community engagement tool where, like a game board, stakeholders can assemble and reassemble color-coded blocks that represent different elements of a potential project. The city of Buffalo plans to use Zhou’s tool for its continuing work on the highway project.

he project also brought forward issues Zhou hadn’t anticipated. Some members of the community, including the Black American Chamber of Commerce, were in favor of restoring the Olmsted parkway in hopes that it would raise property values and benefit homeowners who have had to live for decades with a highway 200 feet from their front doors. Given the park’s important legacy, restoring it seemed like the obvious, most desirable outcome, at first.

But it could lead to the negative effects of gentrification, as research shows that sharply rising property values often make an area prohibitively expensive for Black homeowners and residents, forcing them to sell or move, Zhou noted.

“But then I realized it’s not only about bringing back part of the history,” she said. “It’s more about, how do you really strengthen a community nowadays?”

For D’Oca, the students successfully generated ideas that were “big, bold, and long-term,” but also “sensitive and responsive” to a community’s needs.

“As designers and planners, we too often assume that creativity and reality are at odds: that accommodating community preferences restrains creativity and undermines good design” he said. “I think these students demonstrated that this isn’t the case. I was really impressed with their ability to digest the sometimes-conflicting feedback they received … and create visions that are enticing to people in and out of Gund Hall.”

See the full article here .

five-ways-keep-your-child-safe-school-shootings

Please help promote STEM in your local schools.

Harvard University (US) is the oldest institution of higher education in the United States, established in 1636 by vote of the Great and General Court of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. It was named after the College’s first benefactor, the young minister John Harvard of Charlestown, who upon his death in 1638 left his library and half his estate to the institution. A statue of John Harvard stands today in front of University Hall in Harvard Yard, and is perhaps the University’s bestknown landmark.

Harvard University (US) has 12 degree-granting Schools in addition to the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study. The University has grown from nine students with a single master to an enrollment of more than 20,000 degree candidates including undergraduate, graduate, and professional students. There are more than 360,000 living alumni in the U.S. and over 190 other countries.

The Massachusetts colonial legislature, the General Court, authorized Harvard University (US)’s founding. In its early years, Harvard College primarily trained Congregational and Unitarian clergy, although it has never been formally affiliated with any denomination. Its curriculum and student body were gradually secularized during the 18th century, and by the 19th century, Harvard University (US) had emerged as the central cultural establishment among the Boston elite. Following the American Civil War, President Charles William Eliot’s long tenure (1869–1909) transformed the college and affiliated professional schools into a modern research university; Harvard became a founding member of the Association of American Universities in 1900. James B. Conant led the university through the Great Depression and World War II; he liberalized admissions after the war.

The university is composed of ten academic faculties plus the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study. Arts and Sciences offers study in a wide range of academic disciplines for undergraduates and for graduates, while the other faculties offer only graduate degrees, mostly professional. Harvard has three main campuses: the 209-acre (85 ha) Cambridge campus centered on Harvard Yard; an adjoining campus immediately across the Charles River in the Allston neighborhood of Boston; and the medical campus in Boston’s Longwood Medical Area. Harvard University (US)’s endowment is valued at $41.9 billion, making it the largest of any academic institution. Endowment income helps enable the undergraduate college to admit students regardless of financial need and provide generous financial aid with no loans The Harvard Library is the world’s largest academic library system, comprising 79 individual libraries holding about 20.4 million items.

Harvard University (US) has more alumni, faculty, and researchers who have won Nobel Prizes (161) and Fields Medals (18) than any other university in the world and more alumni who have been members of the U.S. Congress, MacArthur Fellows, Rhodes Scholars (375), and Marshall Scholars (255) than any other university in the United States. Its alumni also include eight U.S. presidents and 188 living billionaires, the most of any university. Fourteen Turing Award laureates have been Harvard affiliates. Students and alumni have also won 10 Academy Awards, 48 Pulitzer Prizes, and 108 Olympic medals (46 gold), and they have founded many notable companies.

Colonial

Harvard University (US) was established in 1636 by vote of the Great and General Court of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. In 1638, it acquired British North America’s first known printing press. In 1639, it was named Harvard College after deceased clergyman John Harvard, an alumnus of the University of Cambridge(UK) who had left the school £779 and his library of some 400 volumes. The charter creating the Harvard Corporation was granted in 1650.

A 1643 publication gave the school’s purpose as “to advance learning and perpetuate it to posterity, dreading to leave an illiterate ministry to the churches when our present ministers shall lie in the dust.” It trained many Puritan ministers in its early years and offered a classic curriculum based on the English university model—many leaders in the colony had attended the University of Cambridge—but conformed to the tenets of Puritanism. Harvard University (US) has never affiliated with any particular denomination, though many of its earliest graduates went on to become clergymen in Congregational and Unitarian churches.

Increase Mather served as president from 1681 to 1701. In 1708, John Leverett became the first president who was not also a clergyman, marking a turning of the college away from Puritanism and toward intellectual independence.

19th century

In the 19th century, Enlightenment ideas of reason and free will were widespread among Congregational ministers, putting those ministers and their congregations in tension with more traditionalist, Calvinist parties. When Hollis Professor of Divinity David Tappan died in 1803 and President Joseph Willard died a year later, a struggle broke out over their replacements. Henry Ware was elected to the Hollis chair in 1805, and the liberal Samuel Webber was appointed to the presidency two years later, signaling the shift from the dominance of traditional ideas at Harvard to the dominance of liberal, Arminian ideas.

Charles William Eliot, president 1869–1909, eliminated the favored position of Christianity from the curriculum while opening it to student self-direction. Though Eliot was the crucial figure in the secularization of American higher education, he was motivated not by a desire to secularize education but by Transcendentalist Unitarian convictions influenced by William Ellery Channing and Ralph Waldo Emerson.

20th century

In the 20th century, Harvard University (US)’s reputation grew as a burgeoning endowment and prominent professors expanded the university’s scope. Rapid enrollment growth continued as new graduate schools were begun and the undergraduate college expanded. Radcliffe College, established in 1879 as the female counterpart of Harvard College, became one of the most prominent schools for women in the United States. Harvard University (US) became a founding member of the Association of American Universities in 1900.

The student body in the early decades of the century was predominantly “old-stock, high-status Protestants, especially Episcopalians, Congregationalists, and Presbyterians.” A 1923 proposal by President A. Lawrence Lowell that Jews be limited to 15% of undergraduates was rejected, but Lowell did ban blacks from freshman dormitories.

President James B. Conant reinvigorated creative scholarship to guarantee Harvard University (US)’s preeminence among research institutions. He saw higher education as a vehicle of opportunity for the talented rather than an entitlement for the wealthy, so Conant devised programs to identify, recruit, and support talented youth. In 1943, he asked the faculty to make a definitive statement about what general education ought to be, at the secondary as well as at the college level. The resulting Report, published in 1945, was one of the most influential manifestos in 20th century American education.

Between 1945 and 1960, admissions were opened up to bring in a more diverse group of students. No longer drawing mostly from select New England prep schools, the undergraduate college became accessible to striving middle class students from public schools; many more Jews and Catholics were admitted, but few blacks, Hispanics, or Asians. Throughout the rest of the 20th century, Harvard became more diverse.

Harvard University (US)’s graduate schools began admitting women in small numbers in the late 19th century. During World War II, students at Radcliffe College (which since 1879 had been paying Harvard University (US) professors to repeat their lectures for women) began attending Harvard University (US) classes alongside men. Women were first admitted to the medical school in 1945. Since 1971, Harvard University (US) has controlled essentially all aspects of undergraduate admission, instruction, and housing for Radcliffe women. In 1999, Radcliffe was formally merged into Harvard University (US).

21st century

Drew Gilpin Faust, previously the dean of the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, became Harvard University (US)’s first woman president on July 1, 2007. She was succeeded by Lawrence Bacow on July 1, 2018.