FNAL Art Image by Angela Gonzales

Fermilab is an enduring source of strength for the US contribution to scientific research world wide.

October 16, 2017

Science contact

Josh Frieman, Director, Dark Energy Survey

Fermilab

frieman@fnal.gov

847-274-0429

Marcelle Soares-Santos, Assistant Professor

Brandeis University

marcelle@brandeis.edu

773-757-8495

Daniel Holz, Professor

University of Chicago

holz@uchicago.edu

505-920-5751

Edo Berger, Professor

Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics

eberger@cfa.harvard.edu

617-495-7914

Media contact

Andre Salles,

Fermilab Office of Communication

asalles@fnal.gov

630-840-6733

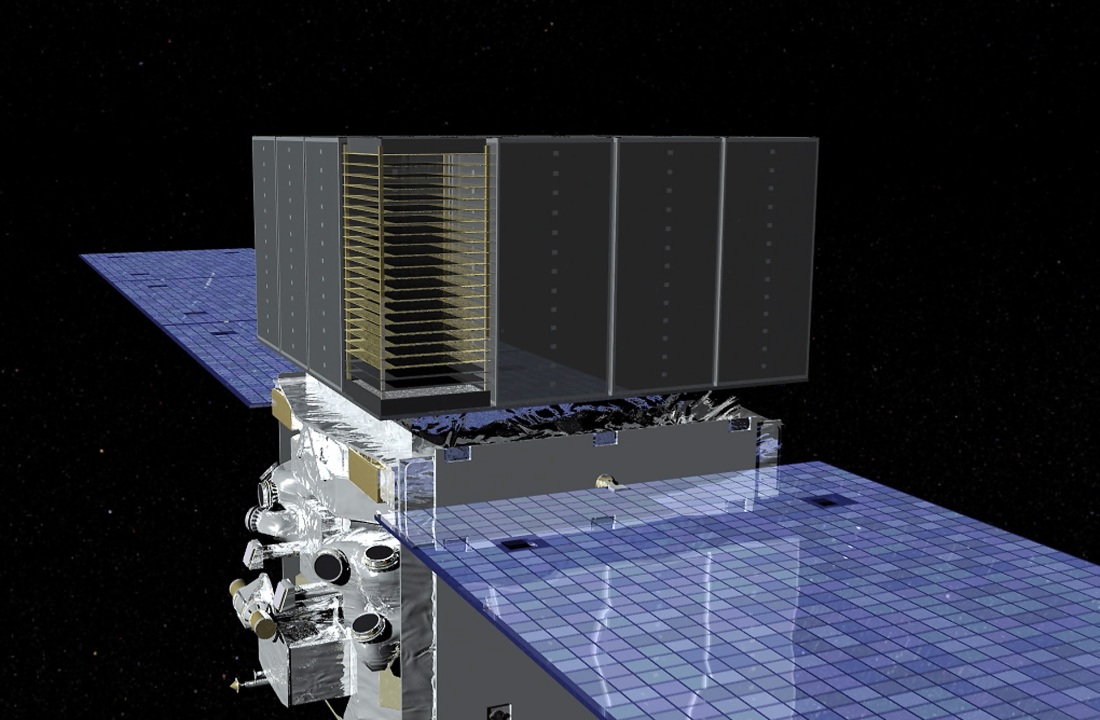

Artist’s rendition of colliding neutron stars creating gravitational waves and a kilonova. Image: Fermilab

Scientists using the Dark Energy Camera have captured images of the aftermath of a neutron star collision, the source of LIGO/Virgo’s most recent gravitational wave detection.

![]()

A team of scientists using the Dark Energy Camera (DECam), the primary observing tool of the Dark Energy Survey, was among the first to observe the fiery aftermath of a recently detected burst of gravitational waves, recording images of the first confirmed explosion from two colliding neutron stars ever seen by astronomers.

Scientists on the Dark Energy Survey joined forces with a team of astronomers based at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA) for this effort, working with observatories around the world to bolster the original data from DECam. Images taken with DECam captured the flaring-up and fading over time of a kilonova — an explosion similar to a supernova, but on a smaller scale — that occurs when collapsed stars (called neutron stars) crash into each other, creating heavy radioactive elements.

This particular violent merger, which occurred 130 million years ago in a galaxy near our own (NGC 4993), is the source of the gravitational waves detected by the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) and the Virgo collaborations on Aug. 17.

Skymap showing how adding Virgo to LIGO helps in reducing the size of the source-likely region in the sky. (Credit: Giuseppe Greco (Virgo Urbino group)

This is the fifth source of gravitational waves to be detected — the first one was discovered in September 2015, for which three founding members of the LIGO collaboration were awarded the Nobel Prize in physics two weeks ago.

This latest event is the first detection of gravitational waves caused by two neutron stars colliding and thus the first one to have a visible source. The previous gravitational wave detections were traced to binary black holes, which cannot be seen through telescopes. This neutron star collision occurred relatively close to home, so within a few hours of receiving the notice from LIGO/Virgo, scientists were able to point telescopes in the direction of the event and get a clear picture of the light.

The image on the left shows the kilonova (just above and to the left of the brightest galaxy) recorded by the Dark Energy Camera. The image on the right was taken several days later and shows that the kilonova has faded. Image: Dark Energy Survey

“This is beyond my wildest dreams,” said Marcelle Soares-Santos, formerly of the U.S. Department of Energy’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory and currently of Brandeis University, who led the effort from the Dark Energy Survey side. “With DECam we get a good signal, and we can show how it is evolving over time. The team following these signals is a well-oiled machine, and though we did not expect this to happen so soon, we were ready for it.”

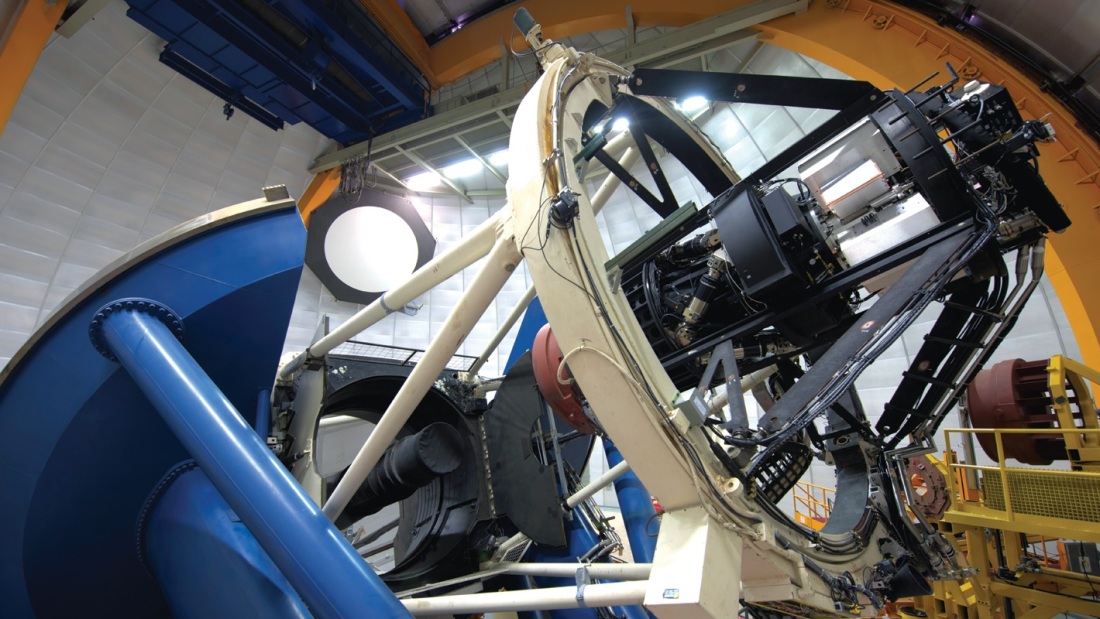

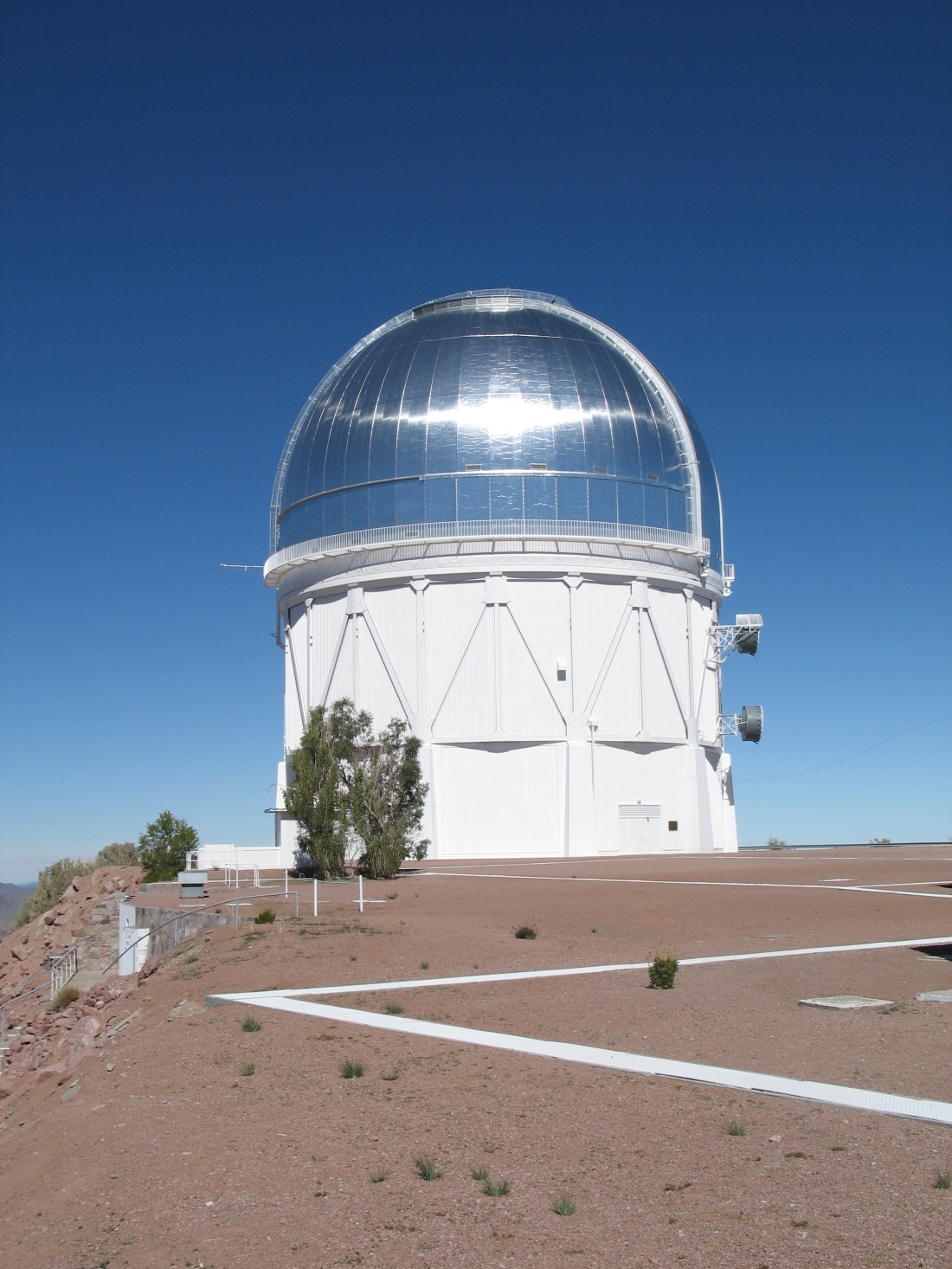

The Dark Energy Camera is one of the most powerful digital imaging devices in existence. It was built and tested at Fermilab, the lead laboratory on the Dark Energy Survey, and is mounted on the National Science Foundation’s 4-meter Blanco telescope, part of the Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory in Chile, a division of the National Optical Astronomy Observatory. The DES images are processed at the National Center for Supercomputing Applications at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Texas A&M University astronomer Jennifer Marshall was observing for DES at the Blanco telescope during the event, while Fermilab astronomers Douglas Tucker and Sahar Allam were coordinating the observations from Fermilab’s Remote Operations Center. “It was truly amazing,” Marshall said. “I felt so fortunate to be in the right place at the right time to help make perhaps one of the most significant observations of my career.”

The kilonova was first identified in DECam images by Ohio University astronomer Ryan Chornock, who instantly alerted his colleagues by email. “I was flipping through the raw data, and I came across this bright galaxy and saw a new source that was not in the reference image [taken previously],” he said. “It was very exciting.”

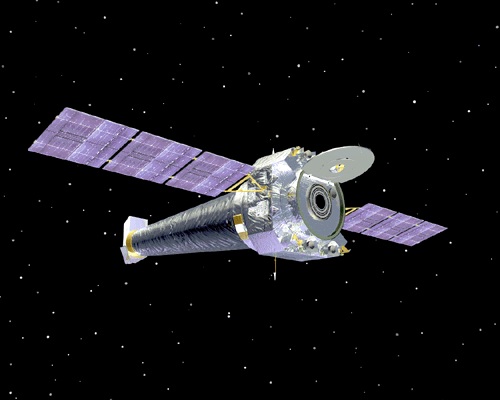

Once the crystal clear images from DECam were taken, a team led by Professor Edo Berger, from CfA, went to work analyzing the phenomenon using several different resources. Within hours of receiving the location information, the team had booked time with several observatories, including NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope and Chandra X-ray Observatory.

Composite picture of stars over the Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory in Chile. Photo: Reidar Hahn/Fermilab

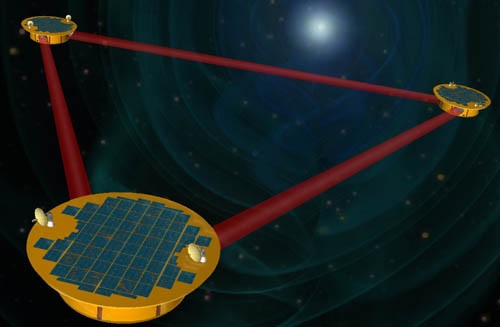

LIGO/Virgo works with dozens of astronomy collaborations around the world, providing sky maps of the area where any detected gravitational waves originated. The team from DES and CfA had been preparing for an event like this for more than two years, forging connections with other astronomy collaborations and putting procedures in place to mobilize as soon as word came down that a new source had been detected. The result is a rich data set that covers “radio waves to X-rays to everything in between,” Berger said.

“This is the first event, the one everyone will remember,” Berger said. “I’m extremely proud of our entire group, who responded in an amazing way. I kept telling them to savor the moment. How many people can say they were there at the birth of a whole new field of astronomy?”

Adding to the excitement of this observation, this latest gravitational wave detection correlates to a burst of gamma rays spotted by NASA’s Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope.

Combining these detections is like hearing thunder and seeing lightning for the very first time, and it opens up a world of new scientific discovery.

“Each of these — the gravitational waves from merging neutron stars, the gamma ray burst and the optical counterpart — could have been separate groundbreaking discoveries, and each could have taken many years,” said Daniel Holz of the University of Chicago, who works on both the DES and LIGO collaborations. “In less than a day, we did it all. This has required many different communities working together to make it all happen. It’s so gratifying to have it be so successful.”

This event also provides a completely new and unique way to measure the present expansion rate of the universe, the Hubble constant, something theorized by Holz and others. Just as astrophysicists use supernovae as “standard candles” (objects of the same intrinsic brightness) to measure cosmic expansion, kilonovae can be used as “standard sirens” (objects of known gravitational wave strength).

LIGO/Virgo can use this to tell the distance to these events, while optical follow-up from DES and others determines the red shift or recession speed; their combination enables scientists to determine the present expansion rate. This new kind of measurement will assist the Dark Energy Survey in its mission to uncover more about dark energy, the mysterious force accelerating the expansion of the universe.

“The Dark Energy Survey team has been working with LIGO for more than two years, refining their process of following up gravitational wave signals,” said Fermilab Director Nigel Lockyer. “It is immensely gratifying to be on the front lines of a discovery this significant, one that required the combined skills of many supremely talented people in many fields.”

The Dark Energy Survey recently began the fifth and final year of its quest to map an area of the southern sky in unprecedented detail. Scientists on DES will use this data to learn more about the effect of dark energy over eight billion years of the universe’s history, in the process measuring 300 million galaxies, 100,000 galaxy clusters and 3,000 supernovae.

Six papers relating to the DECam discovery of the optical counterpart are planned for publication in The Astrophysical Journal. Preprints of all papers are available here: https://www.darkenergysurvey.org/des-gravitational-waves-papers.

“It is tremendously exciting to experience a rare event that transforms our understanding of the workings of the universe,” said France A. Córdova, director of the National Science Foundation (NSF), which funds LIGO and supports the observatory where DECam is housed. “This discovery realizes a long-standing goal many of us have had — that is, to simultaneously observe rare cosmic events using both traditional as well as gravitational-wave observatories. Only through NSF’s four-decade investment in gravitational-wave observatories, coupled with telescopes that observe from radio to gamma-ray wavelengths, are we able to expand our opportunities to detect new cosmic phenomena and piece together a fresh narrative of the physics of stars in their death throes.”

The Dark Energy Survey is a collaboration of more than 400 scientists from 26 institutions in seven countries. Funding for the DES Projects has been provided by the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science, U.S. National Science Foundation, Ministry of Science and Education of Spain, Science and Technology Facilities Council of the United Kingdom, Higher Education Funding Council for England, ETH Zurich for Switzerland, National Center for Supercomputing Applications at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Kavli Institute of Cosmological Physics at the University of Chicago, Center for Cosmology and AstroParticle Physics at Ohio State University, Mitchell Institute for Fundamental Physics and Astronomy at Texas A&M University, Financiadora de Estudos e Projetos, Fundação Carlos Chagas Filho de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico and Ministério da Ciência e Tecnologia, Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, and the collaborating institutions in the Dark Energy Survey, the list of which can be found at http://www.darkenergysurvey.org/collaboration.

Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory, National Optical Astronomy Observatory, is operated by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy (AURA) under a cooperative agreement with the National Science Foundation.

Fermilab is America’s premier national laboratory for particle physics and accelerator research. A U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science laboratory, Fermilab is located near Chicago, Illinois, and operated under contract by the Fermi Research Alliance LLC, a joint partnership between the University of Chicago and the Universities Research Association, Inc. Visit Fermilab’s website at http://www.fnal.gov and follow us on Twitter at @Fermilab.

The DOE Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.

See the full article here .

See also:

From UCSC: “Neutron stars, gravitational waves, and all the gold in the universe”

From UCSC: “Neutron stars, gravitational waves, and all the gold in the universe”

Tim Stephens

Astronomer Ryan Foley says “observing the explosion of two colliding neutron stars” [see https://sciencesprings.wordpress.com/2017/10/17/from-ucsc-first-observations-of-merging-neutron-stars-mark-a-new-era-in-astronomy ]–the first visible event ever linked to gravitational waves–is probably the biggest discovery he’ll make in his lifetime. That’s saying a lot for a young assistant professor who presumably has a long career still ahead of him.

The first optical image of a gravitational wave source was taken by a team led by Ryan Foley of UC Santa Cruz using the Swope Telescope at the Carnegie Institution’s Las Campanas Observatory in Chile. This image of Swope Supernova Survey 2017a (SSS17a, indicated by arrow) shows the light emitted from the cataclysmic merger of two neutron stars. (Image credit: 1M2H Team/UC Santa Cruz & Carnegie Observatories/Ryan Foley)

Carnegie Institution Swope telescope at Las Campanas, Chile, 100 kilometres (62 mi) northeast of the city of La Serena. near the north end of a 7 km (4.3 mi) long mountain ridge. Cerro Las Campanas, near the southern end and over 2,500 m (8,200 ft) high, at Las Campanas, Chile

A neutron star forms when a massive star runs out of fuel and explodes as a supernova, throwing off its outer layers and leaving behind a collapsed core composed almost entirely of neutrons. Neutrons are the uncharged particles in the nucleus of an atom, where they are bound together with positively charged protons. In a neutron star, they are packed together just as densely as in the nucleus of an atom, resulting in an object with one to three times the mass of our sun but only about 12 miles wide.

“Basically, a neutron star is a gigantic atom with the mass of the sun and the size of a city like San Francisco or Manhattan,” said Foley, an assistant professor of astronomy and astrophysics at UC Santa Cruz.

These objects are so dense, a cup of neutron star material would weigh as much as Mount Everest, and a teaspoon would weigh a billion tons. It’s as dense as matter can get without collapsing into a black hole.

THE MERGER

Like other stars, neutron stars sometimes occur in pairs, orbiting each other and gradually spiraling inward. Eventually, they come together in a catastrophic merger that distorts space and time (creating gravitational waves) and emits a brilliant flare of electromagnetic radiation, including visible, infrared, and ultraviolet light, x-rays, gamma rays, and radio waves. Merging black holes also create gravitational waves, but there’s nothing to be seen because no light can escape from a black hole.

Foley’s team was the first to observe the light from a neutron star merger that took place on August 17, 2017, and was detected by the Advanced Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO).

Now, for the first time, scientists can study both the gravitational waves (ripples in the fabric of space-time), and the radiation emitted from the violent merger of the densest objects in the universe.

The UC Santa Cruz team found SSS17a by comparing a new image of the galaxy N4993 (right) with images taken four months earlier by the Hubble Space Telescope (left). The arrows indicate where SSS17a was absent from the Hubble image and visible in the new image from the Swope Telescope. (Image credits: Left, Hubble/STScI; Right, 1M2H Team/UC Santa Cruz & Carnegie Observatories/Ryan Foley)

It’s that combination of data, and all that can be learned from it, that has astronomers and physicists so excited. The observations of this one event are keeping hundreds of scientists busy exploring its implications for everything from fundamental physics and cosmology to the origins of gold and other heavy elements.

A small team of UC Santa Cruz astronomers were the first team to observe light from two neutron stars merging in August. The implications are huge.

ALL THE GOLD IN THE UNIVERSE

It turns out that the origins of the heaviest elements, such as gold, platinum, uranium—pretty much everything heavier than iron—has been an enduring conundrum. All the lighter elements have well-explained origins in the nuclear fusion reactions that make stars shine or in the explosions of stars (supernovae). Initially, astrophysicists thought supernovae could account for the heavy elements, too, but there have always been problems with that theory, says Enrico Ramirez-Ruiz, professor and chair of astronomy and astrophysics at UC Santa Cruz.

The violent merger of two neutron stars is thought to involve three main energy-transfer processes, shown in this diagram, that give rise to the different types of radiation seen by astronomers, including a gamma-ray burst and a kilonova explosion seen in visible light. (Image credit: Murguia-Berthier et al., Science)

A theoretical astrophysicist, Ramirez-Ruiz has been a leading proponent of the idea that neutron star mergers are the source of the heavy elements. Building a heavy atomic nucleus means adding a lot of neutrons to it. This process is called rapid neutron capture, or the r-process, and it requires some of the most extreme conditions in the universe: extreme temperatures, extreme densities, and a massive flow of neutrons. A neutron star merger fits the bill.

Ramirez-Ruiz and other theoretical astrophysicists use supercomputers to simulate the physics of extreme events like supernovae and neutron star mergers. This work always goes hand in hand with observational astronomy. Theoretical predictions tell observers what signatures to look for to identify these events, and observations tell theorists if they got the physics right or if they need to tweak their models. The observations by Foley and others of the neutron star merger now known as SSS17a are giving theorists, for the first time, a full set of observational data to compare with their theoretical models.

According to Ramirez-Ruiz, the observations support the theory that neutron star mergers can account for all the gold in the universe, as well as about half of all the other elements heavier than iron.

RIPPLES IN THE FABRIC OF SPACE-TIME

Einstein predicted the existence of gravitational waves in 1916 in his general theory of relativity, but until recently they were impossible to observe. LIGO’s extraordinarily sensitive detectors achieved the first direct detection of gravitational waves, from the collision of two black holes, in 2015. Gravitational waves are created by any massive accelerating object, but the strongest waves (and the only ones we have any chance of detecting) are produced by the most extreme phenomena.

Two massive compact objects—such as black holes, neutron stars, or white dwarfs—orbiting around each other faster and faster as they draw closer together are just the kind of system that should radiate strong gravitational waves. Like ripples spreading in a pond, the waves get smaller as they spread outward from the source. By the time they reached Earth, the ripples detected by LIGO caused distortions of space-time thousands of times smaller than the nucleus of an atom.

The rarefied signals recorded by LIGO’s detectors not only prove the existence of gravitational waves, they also provide crucial information about the events that produced them. Combined with the telescope observations of the neutron star merger, it’s an incredibly rich set of data.

LIGO can tell scientists the masses of the merging objects and the mass of the new object created in the merger, which reveals whether the merger produced another neutron star or a more massive object that collapsed into a black hole. To calculate how much mass was ejected in the explosion, and how much mass was converted to energy, scientists also need the optical observations from telescopes. That’s especially important for quantifying the nucleosynthesis of heavy elements during the merger.

LIGO can also provide a measure of the distance to the merging neutron stars, which can now be compared with the distance measurement based on the light from the merger. That’s important to cosmologists studying the expansion of the universe, because the two measurements are based on different fundamental forces (gravity and electromagnetism), giving completely independent results.

“This is a huge step forward in astronomy,” Foley said. “Having done it once, we now know we can do it again, and it opens up a whole new world of what we call ‘multi-messenger’ astronomy, viewing the universe through different fundamental forces.”

IN THIS REPORT

Neutron stars

A team from UC Santa Cruz was the first to observe the light from a neutron star merger that took place on August 17, 2017 and was detected by the Advanced Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO)

Graduate students and post-doctoral scholars at UC Santa Cruz played key roles in the dramatic discovery and analysis of colliding neutron stars.Astronomer Ryan Foley leads a team of young graduate students and postdoctoral scholars who have pulled off an extraordinary coup. Following up on the detection of gravitational waves from the violent merger of two neutron stars, Foley’s team was the first to find the source with a telescope and take images of the light from this cataclysmic event. In so doing, they beat much larger and more senior teams with much more powerful telescopes at their disposal.

“We’re sort of the scrappy young upstarts who worked hard and got the job done,” said Foley, an untenured assistant professor of astronomy and astrophysics at UC Santa Cruz.

IN THIS REPORT

Scientific Papers from the 1M2H Collaboration

Coulter et al., Science, Swope Supernova Survey 2017a (SSS17a), the Optical Counterpart to a Gravitational Wave Source

Drout et al., Science, Light Curves of the Neutron Star Merger GW170817/SSS17a: Implications for R-Process Nucleosynthesis

Shappee et al., Science, Early Spectra of the Gravitational Wave Source GW170817: Evolution of a Neutron Star Merger

Kilpatrick et al., Science, Electromagnetic Evidence that SSS17a is the Result of a Binary Neutron Star Merger

Siebert et al., ApJL, The Unprecedented Properties of the First Electromagnetic Counterpart to a Gravitational-wave Source

Pan et al., ApJL, The Old Host-galaxy Environment of SSS17a, the First Electromagnetic Counterpart to a Gravitational-wave Source

Murguia-Berthier et al., ApJL, A Neutron Star Binary Merger Model for GW170817/GRB170817a/SSS17a

Kasen et al., Nature, Origin of the heavy elements in binary neutron star mergers from a gravitational wave event

Abbott et al., Nature, A gravitational-wave standard siren measurement of the Hubble constant (The LIGO Scientific Collaboration and The Virgo Collaboration, The 1M2H Collaboration, The Dark Energy Camera GW-EM Collaboration and the DES Collaboration, The DLT40 Collaboration, The Las Cumbres Observatory Collaboration, The VINROUGE Collaboration & The MASTER Collaboration)

Abbott et al., ApJL, Multi-messenger Observations of a Binary Neutron Star Merger

PRESS RELEASES AND MEDIA COVERAGE

Watch Ryan Foley tell the story of how his team found the neutron star merger in the video below. 2.5 HOURS.

Credits

Writing: Tim Stephens

Video: Nick Gonzales

Photos: Carolyn Lagattuta

Header image: Illustration by Robin Dienel courtesy of the Carnegie Institution for Science

Design and development: Rob Knight

Project managers: Sherry Main, Scott Hernandez-Jason, Tim Stephens

See the full article here .

Shane Telescope at UCO Lick Observatory, UCSC

Lick Automated Planet Finder telescope, Mount Hamilton, CA, USA

The University of California, Santa Cruz, opened in 1965 and grew, one college at a time, to its current (2008-09) enrollment of more than 16,000 students. Undergraduates pursue more than 60 majors supervised by divisional deans of humanities, physical & biological sciences, social sciences, and arts. Graduate students work toward graduate certificates, master’s degrees, or doctoral degrees in more than 30 academic fields under the supervision of the divisional and graduate deans. The dean of the Jack Baskin School of Engineering oversees the campus’s undergraduate and graduate engineering programs.

UCSC is the home base for the Lick Observatory.

Lick Observatory’s Great Lick 91-centimeter (36-inch) telescope housed in the South (large) Dome of main building

Search for extraterrestrial intelligence expands at Lick Observatory

New instrument scans the sky for pulses of infrared light

March 23, 2015

By Hilary Lebow

The NIROSETI instrument saw first light on the Nickel 1-meter Telescope at Lick Observatory on March 15, 2015. (Photo by Laurie Hatch) UCSC Lick Nickel telescope

Astronomers are expanding the search for extraterrestrial intelligence into a new realm with detectors tuned to infrared light at UC’s Lick Observatory. A new instrument, called NIROSETI, will soon scour the sky for messages from other worlds.

“Infrared light would be an excellent means of interstellar communication,” said Shelley Wright, an assistant professor of physics at UC San Diego who led the development of the new instrument while at the University of Toronto’s Dunlap Institute for Astronomy & Astrophysics.

Wright worked on an earlier SETI project at Lick Observatory as a UC Santa Cruz undergraduate, when she built an optical instrument designed by UC Berkeley researchers. The infrared project takes advantage of new technology not available for that first optical search.

Infrared light would be a good way for extraterrestrials to get our attention here on Earth, since pulses from a powerful infrared laser could outshine a star, if only for a billionth of a second. Interstellar gas and dust is almost transparent to near infrared, so these signals can be seen from great distances. It also takes less energy to send information using infrared signals than with visible light.

UCSC alumna Shelley Wright, now an assistant professor of physics at UC San Diego, discusses the dichroic filter of the NIROSETI instrument. (Photo by Laurie Hatch)

Frank Drake, professor emeritus of astronomy and astrophysics at UC Santa Cruz and director emeritus of the SETI Institute, said there are several additional advantages to a search in the infrared realm.

“The signals are so strong that we only need a small telescope to receive them. Smaller telescopes can offer more observational time, and that is good because we need to search many stars for a chance of success,” said Drake.

The only downside is that extraterrestrials would need to be transmitting their signals in our direction, Drake said, though he sees this as a positive side to that limitation. “If we get a signal from someone who’s aiming for us, it could mean there’s altruism in the universe. I like that idea. If they want to be friendly, that’s who we will find.”

Scientists have searched the skies for radio signals for more than 50 years and expanded their search into the optical realm more than a decade ago. The idea of searching in the infrared is not a new one, but instruments capable of capturing pulses of infrared light only recently became available.

“We had to wait,” Wright said. “I spent eight years waiting and watching as new technology emerged.”

Now that technology has caught up, the search will extend to stars thousands of light years away, rather than just hundreds. NIROSETI, or Near-Infrared Optical Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence, could also uncover new information about the physical universe.

“This is the first time Earthlings have looked at the universe at infrared wavelengths with nanosecond time scales,” said Dan Werthimer, UC Berkeley SETI Project Director. “The instrument could discover new astrophysical phenomena, or perhaps answer the question of whether we are alone.”

NIROSETI will also gather more information than previous optical detectors by recording levels of light over time so that patterns can be analyzed for potential signs of other civilizations.

“Searching for intelligent life in the universe is both thrilling and somewhat unorthodox,” said Claire Max, director of UC Observatories and professor of astronomy and astrophysics at UC Santa Cruz. “Lick Observatory has already been the site of several previous SETI searches, so this is a very exciting addition to the current research taking place.”

NIROSETI will be fully operational by early summer and will scan the skies several times a week on the Nickel 1-meter telescope at Lick Observatory, located on Mt. Hamilton east of San Jose.

The NIROSETI team also includes Geoffrey Marcy and Andrew Siemion from UC Berkeley; Patrick Dorval, a Dunlap undergraduate, and Elliot Meyer, a Dunlap graduate student; and Richard Treffers of Starman Systems. Funding for the project comes from the generous support of Bill and Susan Bloomfield.

Please help promote STEM in your local schools.

Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory (Fermilab), located just outside Batavia, Illinois, near Chicago, is a US Department of Energy national laboratory specializing in high-energy particle physics. Fermilab is America’s premier laboratory for particle physics and accelerator research, funded by the U.S. Department of Energy. Thousands of scientists from universities and laboratories around the world

collaborate at Fermilab on experiments at the frontiers of discovery.